Health + Medicine

The Microbiome, a Key to Treating Disease

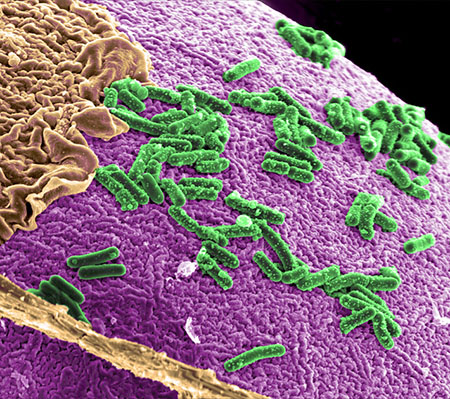

There’s a new buzzword in the health field these days: the microbiome, the trillions of microscopic bacteria, fungi and viruses on and in our bodies that may hold a key to understanding and treating a range of maladies. A growing appreciation of the extent of this ecosystem and its biological benefits has inspired a new frontier in medical research—along with plenty of marketing hype that may confuse and mislead patients and consumers.

So, what do we know? That we live in a complex and, ideally, symbiotic relationship with our microbes, which reside primarily in the gut. They support us in a range of functions we are just beginning to understand—from digestion and weight management to mental health and immune support. And what do they ask of us? Fiber. That’s their primary fuel source, and a healthy dose of it helps to keep them, and us, humming along.

But many features of our modern lifestyle throw off the balance of good and bad bugs that make up the microbiome.

The major culprit is the Western diet, which is low in fiber and high in sugar. It feeds the bad bugs and starves the good ones. Without enough fiber, microbes feed on the protective mucosal barrier that lines the intestine, which could trigger intestinal inflammation. This inflammation stems from an immune response to a perceived threat, which could be a bacteria, virus, parasite or undigestible protein such as gliadin in gluten, according to Dr. Alessio Fasano, division chief of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Furthermore, our reliance on antibiotics wipes out both the microbes we don’t want along with those we want, altering the microbiome and putting us at risk. This is the case with infections of C. difficile, which typically follow antibiotic use and can colonize the gut without beneficial bugs to keep them in check. C. difficile bacterium can cause debilitating diarrhea, inflammation of the colon and even death. (Studies have shown that probiotics containing Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and bacillus may prevent C. difficile.)

Much of the excitement about the microbiome stems from a landmark 2012 report by the National Institutes of Health that revealed a new gene sequencing technology to map microbial DNA. Based on samples collected from 242 healthy Americans, the NIH Human Microbiome Project found that people have 100 trillion microbial cells, three times the number of human cells. The NIH has just completed a second iteration of the project, studying the microbiome of pregnant women and people with inflammatory bowel disease and type 2 diabetes.

“Almost every disease you could think of, there are people looking at the microbiome,” says Phil Daschner, program director of the National Cancer Institute’s branch of immunology, hematology and etiology. Daschner co-chairs a committee that coordinates microbiome research at the NIH, where 21 of its 27 institutes and centers boast a microbiome program.

A key tool for studying the microbiome is fecal microbial transplant (FMT), the transfer of stool from a healthy donor into the colon of a patient with C. difficile to repopulate the gut with good bacteria. Though it’s a crude instrument, FMT has proven remarkably successful in curing recurrent infections of C. difficile, which each year sickens half a million people in the United States and claims 15,000 lives. Practitioners of this new treatment report staggering, even miraculous, success stories.

At Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, a recent transplant was performed on a severely immunocompromised patient who suffered paralysis of his large intestine and was considered too sick for surgery. Two days after the transplant, the patient recovered, according to Dr. Jacob Strahilevitz, who heads Hadassah’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Service and Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

Despite the excitement of such promising therapy, experts caution that the treatment lacks sufficient studies and standards—or Food and Drug Administration approval.

“We don’t even know what’s in a very clean capsule of FMT or why it’s working,” Daschner said.

Still, researchers are exploring FMT for inflammatory bowel disease and the concept of so-called super donors, those with a wide variety of intestinal flora whose stool has given recipients the greatest benefit.

These are just a few examples of the myriad investigations underway as researchers consider manipulating the microbiome to treat everything from autism to cancer.

Meanwhile, as we uncover the links between the state of our microbiome and ourselves, what can we do to fortify our gut?

The NIH suggests limiting antibiotic use and opting for simple handwashing over antibacterial soap and hand sanitizers.

And if you’re preparing to become a mother, vaginal delivery and breastfeeding have been shown to transmit protective microbes to newborns.

But if those options aren’t possible, don’t despair. Microbes are fragile and fleeting, adapting quickly to your daily choices, according to Dr. Robynne Chutkan, integrative gastroenterologist and founder of the Digestive Center for Wellness in Washington, D.C.

“The most important thing is what you eat every day,” says the author of The Microbiome Solution: A Radical

New Way to Heal Your Body from the Inside Out. Avoid the sugary, processed foods so prevalent in the American diet and build a healthy gut with fibrous vegetables, especially leafy greens.

“People don’t want to do that,” she said. “They want to take a probiotic gummy bear.”

Dr. Chutkan and others warn consumers to tread carefully when it comes to probiotics since science has yet to determine whether, how and what kinds of probiotic strains may help. Not only is the supplement industry unregulated, raising concern about the presence of unstudied and potentially harmful pathogens, but only a few probiotic strains have been found effective for certain conditions. And anyone with a health condition such as a compromised immune system could be endangered by these products.

“We are just crawling right now,” said Dr. Fasano, underscoring the infancy of the field and his concern over shortcuts.

As complicated as the subject is, the steps toward better health are straightforward: Get plenty of fruits and vegetables as well as sleep and exercise, use antibiotics sparingly and avoid stress. “The solution is under our nose,” Dr. Fasano said.

Taken literally, you might start with what’s on your plate.

MICROBIOME RESEARCH: A SAMPLING

In 2017, scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Parker Institute found that metastatic melanoma patients who responded well to immunotherapy treatment had a greater diversity of gut bacteria than those who didn’t, and that certain bacterial strains were correlated with both disease progression and remission. In a follow-up to the study, researchers found that patients on a high-fiber diet not only had a more diverse array of gut microbes but also were five times as likely to respond to immunotherapy treatment as those on a low-fiber diet. The study also found that probiotic use was associated with poorer responses to immunotherapy.

At Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, researchers altered autistic behavior in mice with bacterium that restored social behavior. In each of the known origins for autism spectrum disorders—genetic, environmental and idiopathic—researchers found that L. reuteri could rectify social deficits and its particular pathway, promoting social behavior through the vagus nerve, which connects the gut and the brain.

“We have begun to decipher the precise mechanism by which a gut microbe modulates brain function and behavior. This could be key in the development of new and more effective therapies,” according to Dr. Mauro Costa-Mattioli, director of Baylor’s Memory and Brain Research Center.

Rachel Pomerance Berl is a freelance writer living in Bethesda, Md.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply