Health + Medicine

Feature

Treating Liver Disease

Two years ago, Rochelle Rodney Lando took a vacation in Greece and got bitten by a dog. Back home in Jerusalem, the once energetic curtain designer became so weak she had to ask one client to measure the windows she had come to dress.

“I turned yellow, and then I went to Hadassah,” said Lando. “They found I was allergic to the antibiotic prescribed for the dog bite and now had irreversible liver damage.”

Her illness gave her a new appreciation for this often ignored yet vitally important organ. Before getting bitten, “I’d never thought much about my liver,” she added.

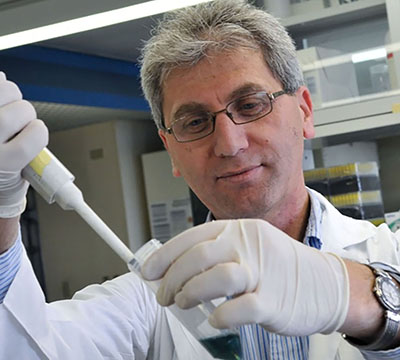

In its complexity and multiple functions within the body, “the liver puts to shame the heart, lungs and other headline-grabbers,” noted Dr. Rifaat Safadi, 54, director of the 30-year-old liver unit at the Hadassah Medical Organization in Jerusalem. Three pounds of reddish-brown tissue tucked under the diaphragm, the liver churns out over 1,000 different types of enzymes to help digest food, store energy and wash out toxins. Among its more than 500 essential jobs are regulating blood flow and clearing the bloodstream of harmful substances, such as caffeine and alcohol, as well as producing dozens of vitamins, antibodies and proteins.

It is therefore alarming that the incidence of disease in this all-important organ is exploding due to both lifestyle and environmental factors, said Dr. Safadi. According to a 2018 report from the European Association for the Study of the Liver, liver disease accounts for two million deaths a year worldwide.

Lando, who was born in Boston and made aliyah in 1986, is among the 7,000 patients admitted annually to Hadassah’s busy liver unit, which treats a range of ailments, from heatstroke and cirrhosis to fatty liver disease and congenital and autoimmune disorders.

The number of patients would triple, said Dr. Safadi, with larger facilities. “Not only do viral, malignant and hereditary disorders continue targeting the liver,” he said, “but people are living longer and embracing lifestyles that make them unfit and obese. This results in a rising number of liver patients”—up by 2,000 from only four years ago.

Part of Hadassah’s internal medicine division, the unit has no beds of its own and hospitalizes its patients in the internal medicine and surgery departments. “We frequently overflow the facility, with three patients hospitalized in two-patient rooms,” Dr. Safadi said. The renovation of Hadassah’s Round Building, the goal of Hadassah’s current Full Circle Campaign: 360° of Healing, will alleviate the congestion. The plan is for the refurbished building to include 16 beds dedicated to an expanded liver facility—which will “save even more lives and allow us to improve our service and prepare for the future,” Dr. Safadi said.

One of the lives the unit has already saved is that of Sara Quasrawi. A smiling 18-year-old from Bethlehem, her face framed by a pink hijab, she studies political science at Al-Quds University and wants to be a diplomat. “Last summer, I went running in the desert near Jericho and collapsed,” she said. Quasrawi had suffered heatstroke and was in liver failure.

“The first step was keeping her alive, either until her liver regenerated or we could transplant her,” said Dr. Safadi. Because chances of regeneration were remote, “we prepared for transplantation, with the patient’s mother as the living donor. The liver can rebuild itself within months, even with 80 percent cut away. Thankfully, youth was on the patient’s side. Her liver function returned, and transplant plans were canceled.”

For patients with end-stage liver disease, however, organ transplantation is the sole option. The number of liver transplants at Hadassah has doubled from 12 in 2016 to 24 last year and will likely more than triple this year. Hadassah’s success rates are on par with the best worldwide: a one-year survival rate of 89 percent and 75 percent after five years, according to a 2016 data report from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, a United States government agency.

Katrina, 51, a mother of two, received a new liver at Hadassah in 2017. A caregiver from Moldova who asked not to disclose her last name, she and her husband, Paul, who works at the Apple R&D center in Haifa, have lived in Israel for eight years. Katrina woke one day feeling ill. Five months later, she was in a near vegetative state, diagnosed with Wilson’s disease, a rare genetic disorder in which copper builds up in the body. Her liver, destroyed by copper overload, no longer functioned; she needed a new one to survive. The transplant waiting list, however, was 1,160 people long, and although Katrina and her family have permanent-resident status in Israel, she is a noncitizen and was therefore ineligible to join the list.

“As a bridge to transplant, she was put on a machine known as MARS,” said Dr. Merhav Hadar, Hadassah’s transplantation director. MARS (molecular absorbent recirculation system) is essentially liver dialysis, filtering toxins from the blood. “We fought not only to get her onto the transplant list, but at its very top.” Within hours of approval by the National Transplant Center, the government body that manages the country’s organ donation system, a liver became available—and five hours in surgery gave Katrina a new liver and a new life.

San Francisco-born Moshe Pomerantz, 67, a telecommunications engineer who today lives in Ofra, north of Jerusalem, was a unit patient for years before receiving a liver transplant. A father of five and grandfather of 11, he is battling primary sclerosing cholangitis, the inflammatory autoimmune illness that put him in liver failure.

“I gained weight, my stomach swelled, and I had trouble breathing,” said Pomerantz. “All of which, I learned, indicated portal hypertension,” an increase in pressure on the portal vein often caused by liver disease. Today, he comes to the hospital for monitoring and the immunosuppressive agents, antihypertensive medications and prophylactics essential for all post-transplant patients.

“I’m in lifelong follow-up,” he said. “Without Hadassah, I wouldn’t be here. I’m always aware of that, especially when I’m with my grandchildren.”

For 40-year-old former journalist Oshrat Ohana Nagar from Beit Shemesh, the issue was not grandchildren, but children. “Three years ago, I had a 15-year-old from an earlier marriage and a baby, but desperately wanted another child,” she said. Nagar, however, has primary biliary cholangitis, a chronic autoimmune illness that destroys the liver’s bile ducts. Unaware that the disease can also affect a woman’s ability to carry a child to term, she had casually mentioned a sixth miscarriage to

Dr. Safadi.

“He immediately said, ‘Tell me next time you get pregnant, and we’ll help.’ ” When she became pregnant once more, Nagar was given a cocktail of medications to maintain the pregnancy and regulate her liver function. “Each additional week I carried my baby was a celebration,” she added, thankful to Dr. Safadi and Hadassah obstetrician Dr. Shlomo Yahalomy, both of whom “kept me and my baby alive.”

Afik arrived eight weeks early weighing just 4.2 pounds, but he was crying and breathing on his own. “The birth was magical,” said Nagar. Her liver values have improved, but Nagar must check in regularly with Hadassah to follow the progression of the disease. Fatigue and bone, joint and muscle pain brought on by her illness have cut short her career, but she is still able to care for her three children.

With research ongoing at Hadassah and worldwide, answers have been found to some liver ailments. Since the 1990s, for example, vaccines against hepatitis A and B were developed, largely at Hadassah under the direction of Dr. Daniel Shouval, former head of the liver unit. As research and subsequent treatment protocols weaken one liver enemy, another takes its place, and fatty liver disease has now become a key research focus at Hadassah. This illness, in which fat displaces functioning liver cells, can progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer and is estimated by the National Institutes of Health to affect up to 20 percent of adults in industrialized nations. Largely linked to lifestyle—obesity, lack of physical exercise, excessive alcohol consumption—genetics are also in play, as the family of 49-year-old Jerusalem accountant Khaled Khalil shows.

“My father, two cousins and I all have it,” he said. “I didn’t even know until two years ago, when I had stomach pain. My wife, Hoyada, is a nurse at Hadassah, so that’s where I went—and learned I needed a liver transplant. I had four kids in school. Would I see them grow up? When a liver became available, I wasn’t well enough for surgery. I waited three months in the hospital for another.

“Today, with a new liver, I’m doing O.K.,” continued Khalil. “I don’t eat junk food, I go to the gym and press my kids to do the same.”

Compared with transplant patients such as Khalil, dog-bite victim Rochelle Rodney Lando—who is on medication to slow the progress of her cirrhosis—knows she is relatively lucky. “My story is absurd!” she exclaimed. “I went to an archaeology museum in Greece, kept my distance from a mother dog with pups, only to feel its very sharp teeth on me. I wasn’t even worrying about the right thing—my fear was rabies. Even the diagnosis is an embarrassment: I have cirrhosis, even though I’ve never been a heavy drinker.”

But, she added with a smile, “Hadassah got it under control.”

Wendy Elliman is a British-born science writer who has lived in Israel for more than four decades.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

sylvia berger says

Looking for help. My grandson was born with Biliary Atresia, at 6 months received a new liver, was doing well so doctors lowered his anti rejection medicine too aggressive, which cause major complications, his numbers are very high and they want to injected toxic medicine to get his levels down!

Can you help he’s in Jackson Memorial Miami Pediatric Dr. Garcia is his doctor.

Need HELP!