American View

Feature

Pittsburgh Jews Resilient After Squirrel Hill Tragedy

Year after year, Pittsburgh has been named one of the country’s most livable cities, according to the Global Liveability Index. In 2018, The Economist magazine, which determines the rankings, placed it higher than any other city in the continental United States. (Only Honolulu ranked higher.)

Pittsburgh residents are justifiably proud. Those who live in the city’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood—home to approximately 13,000 Jews and one of the largest urban Jewish enclaves outside New York City—share that pride, describing it as a diverse neighborhood where people of all colors and creeds coexist in harmony.

In such a peaceful setting, says Barbara Burstin, a historian and the author of several books about Steel City Jews, the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue on October 27 felt “like a dagger in the heart. It has shaken people to the core.”

The question some are asking now is: Will Pittsburgh—and Squirrel Hill—bounce back, or will this horrific tragedy that took the lives of 11 individuals destroy its livability for Jews and non-Jews alike for the foreseeable future?

To Marshall Hershberg, a co-vice president of the Squirrel Hill Urban Coalition and a neighborhood resident for more than 50 years, the answer is clear. “We will overcome this tragedy. We are a very resilient community and have received such a positive outpouring of support,” notes the past president and past board chair of the Young Peoples Synagogue.

He says he is especially grateful to the city’s first responders and police. Positive steps began immediately after the shooting, he says, with the security department of the United Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh and law enforcement working closely to meet the community’s heightened safety concerns—particularly at preschools and day schools. “My personal preference is not to have armed guards,” Hershberg says, looking ahead to debates over how best to protect the area’s 49,000 Jews, 26 percent of whom reside in Squirrel Hill, with the rest living in outlying suburbs. He prefers stepped-up patrols “with a bigger presence,” he says, and increased safety training to help people be more aware of and respond more rapidly to potential threats.

In 2017, the federation introduced a rigorous security program with measures that include ensuring that first responders have blueprints of synagogues and teach people to run and hide rather than move toward the source of a commotion, among other precautions, according to Adam Hertzman, the federation’s director of marketing. These protocols, barely a year old, are credited with preventing more injuries and death at the hands of gunman Robert Bowers, who reportedly stormed into Tree of Life declaring “All Jews must die!”

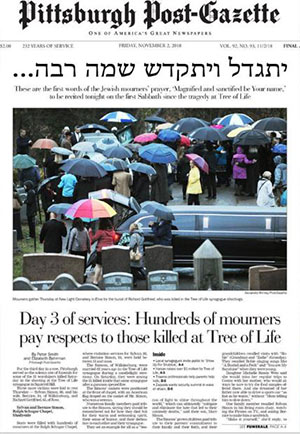

Longtime residents, newcomers and former residents alike echo Hershberg’s belief in Pittsburgh’s tenacity. Burstin, a 40-year resident who teaches at both the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, says she was heartened by the huge turnout at protests and events to memorialize the dead. She was likewise struck by her students’ outpouring of grief. The community will recover, Burstin believes, “but I do not know how long it will take.”

Will Pittsburgh’s pre-eminent colleges and universities continue to attract students in the meantime? “Absolutely!” says Erica Vonderheid, who moved to Squirrel Hill from New Jersey last year to study at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Nursing. “The massacre would not have changed my mind. It might even have made me more likely to move to Squirrel Hill to be in solidarity with the people who were targeted.”

Author Helen Lippman first reported on Pittsburgh for Hadassah Magazine in 2015, when she wrote The Jewish Traveler: Pittsburgh

For Jewish native sons and daughters who have moved away from Pittsburgh, the tragedy left them pining for “home.”

“It’s very hard not being there with them,” says Joseph Cohen, who was a lifelong resident of Pittsburgh until two years ago when he moved to Charleston, W. Va., to become the executive director of the ACLU of West Virginia. Before that, he was a congregant at Squirrel Hill’s Temple Sinai and a graduate of the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Law. He still has family in Pittsburgh.

“A friend of ours, Dan Stein, was one of the 11 people who were killed,” Cohen says, noting that Stein—whose wife, Sharyn, was a prominent Hadassah volunteer—used to work with his wife, Anita Cohen. “It’s strange because we’re mourning him. But I’m also mourning for Pittsburgh, which is such a big part of me.

“My brother called when the shooting was taking place, before any details were known, and I was very frightened,” Cohen adds. “But I knew even then that Pittsburgh would set an example and show the rest of us what justice and compassion look like. I know that the Jewish community and the city as a whole will double down on opening itself to refugees, and to the ‘other.’ ”

“My brother called when the shooting was taking place, before any details were known, and I was very frightened,” Cohen adds. “But I knew even then that Pittsburgh would set an example and show the rest of us what justice and compassion look like. I know that the Jewish community and the city as a whole will double down on opening itself to refugees, and to the ‘other.’ ”

Those interviewed for this article emphasize that the shooting at Tree of Life was the act of one lone hater. In contrast, they point out, messages of love and solidarity abound. You can spot them on T-shirts, emblazoned on Facebook profiles, stitched onto professional sports’ jerseys of Pittsburgh teams, reinforced at communal vigils and shared throughout the country from the bimah of synagogues that sponsored solidarity Shabbats over the weekend.

Helen Lippman, a freelance writer based in Montclair, NJ, was the author of Hadassah Magazine‘s Jewish Traveler feature on Pittsburgh in 2015.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply