Being Jewish

Commentary

Amos Oz on Challenging God, in Search of Justice

The Jews as a people are not disposed to obedience. Never have been. Moses could tell you how unaccustomed the Israelites are to being obedient. God Himself complains throughout the Bible that the Israelites are insubordinate: The people argue with Moses; Moses argues with God; Moses hands in his resignation and eventually backtracks, but only after negotiating with God, who gives in and accepts his main demands (Exodus 32:31-33). Abraham bargains with God over Sodom like a used-car salesman: Fifty righteous men? Forty? Thirty? Twenty? Would you settle for ten? And when it turns out that there are not even ten righteous men in Sodom, Abraham does not beg God to forgive him for his impudence. On the contrary. He utters what might be the boldest words in the Bible: “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do justly?” (Genesis 18:25). In other words: You may be the judge of this entire land, but you are not above the law.

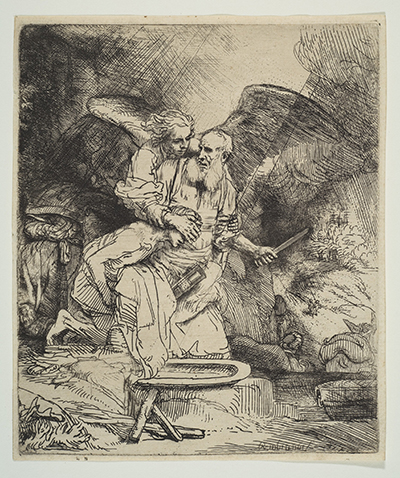

However, a few chapters later, the same Abraham is willing to sacrifice his son, Isaac, out of blind obedience. How might we bridge the chasm between the Abraham who fights God on behalf of strangers and the Abraham who does not hesitate when God commands him to slaughter his own son? The Israeli writer Shulamith Hareven offers a fascinating interpretation of the Binding of Isaac. Like all commentators, Hareven agrees that Abraham was being tested. But contrary to the traditional readings, she believes that Abraham utterly failed the test, because in fact he should have told God, “You yourself forbade us to make human sacrifices, and so I refuse to sacrifice my son.” Abraham failed because he said, “Yes, sir!” instead of declaring, “That is a patently illegal order with a black flag waving above it.”

And in recent generations, Hasidic rabbis have demanded that God appear before a rabbinical court to justify the terrible things occurring in this world. God, of course, does not appear, but the summons is still valid. The rabbis wait in the earthly court for Him to finally explain why “the righteous suffer and the wicked prosper.”

This rebellious streak is interwoven throughout Jewish history. A thread leads from the offenses hurled at the heavens in the Torah, in the Prophets, in the Book of Job, in the Gemara and in Hasidic tales, all the way to Uri Zvi Greenberg’s wonderful yet horrifying poem, “At the End of Roads Stands Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev and Demands a Great Answer.” In this post-Holocaust poem, Levi Yitzhak castigates God by asking, more or less, “Where were you? How could you?”

Decades later, in his poem “God Full of Mercy,” Yehuda Amichai wrote, “Were God not full of mercy/there would be mercy in the world, and not just in Him.” It is Amichai who is the true heir to the finest of Jewish culture. He carries the psychosocial and moral genes of Abraham arguing for Sodom.

This is the anarchist core, the rebellious gene that has flickered for thousands of years in Jewish culture. We don’t just follow orders. We want justice, and we demand it even from the Creator. “Justice, justice shalt thou pursue.”

A young man searching for lost she-asses and a shepherd struck by inspiration can be anointed king of Israel or write the Book of Psalms. A sycamore fig farmer can turn into a prophet. An illiterate shepherd, an unknown shoemaker, a work-weary blacksmith or even a rehabilitated thief can go on to teach the Torah, write interpretations and leave their imprint on the daily lives of every Jewish person for millennia. Yet they were each dogged, almost always, by the question, How do we know you are genuine? You may really be a sage of the Torah, but on the neighboring street lives another sage, who proposes a completely different conclusion from yours. Not infrequently, it transpires that “both these and those are the words of the living God.” And often the disagreement is not a curse but a blessing, “an argument for the sake of heaven’s name.” And in a rare moment of grace, the Lord Himself might admit His error, smile and say, “My children have triumphed over me.”

In Jewish history, the question of interpretive authority has usually been decided by partial consensus rather than unanimously. The history of Jewish culture in the past millennia is a series of bitter disputes, including a few tinged with malicious urges, and some wonderful and fertile ones. The Jewish people often had no authoritative mechanism for formal decision-making, at least not since the decline of the Sanhedrin. A particular rabbi might be considered greater than another rabbi simply because many people think him greater.

Jewish culture has been built with the creative energy arising from tension between the kohen and the prophet, between Pharisees and Sadducees, between the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai, between Sephardi and Ashkenazi prayer services, between Hasidim and their opponents (Misnagdim), between the devout and the proponents of Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah), between Zionists and anti-Zionists, between religious and secular, between hawks and doves—to this very day.

Jewish culture at its finest is a culture of give and take. Of acuity and powers of persuasion. And sometimes of ties: When the greatest minds were unable to agree on a solution, they would declare a tie, or in Hebrew, teko, a term still used in colloquial Hebrew, and which, according to one derivation, is the acronym of an Aramaic phrase meaning “the Tishbite (Elijah) will settle the question when he comes.” In other words: Never mind, we’ll agree to disagree until Elijah the prophet turns up and makes the call. We can certainly live in an open-ended situation. But there is one crucial caveat: Arguments must be conducted without resort to violence.

Jewish culture sanctifies disagreement for the sake of heaven’s name. Undeniably, it is also sometimes a culture of aggressive impulses—of power, authority and honor—disguised as disagreement for the sake of heaven’s name. And to my mind, this heritage coexists superbly with the ideas of pluralistic democracy. One might say that the tradition of arguments and disputes in Jewish culture is analogous to the musical concept of counterpoint as well as to the notion of human polyphony, whereby the community is viewed as a chorus of different voices, or different instruments orchestrated by an agreed set of rules.

Many lights, not one light. Many beliefs and opinions, not one.

Amos Oz is an award-winning author living in Tel Aviv. This column is adapted from his book Dear Zealots: Letters from a Divided Land, translated by Jessica Cohen, to be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in November 2018.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply