Books

Non-fiction

The Joys of Torah in English Translation

In 1604, centuries later and on another continent, England’s King James convened the Hampton Court Conference and conceived of a new English translation of that very same Hebrew Bible with a more modest contingent of 47 scholars, all of them members of the Church of England. Their work, by an official act of Parliament, became known as the Authorized Version, more commonly referred to as the King James Bible and, in academic sarcasm, translation by consensus.

In December, a new milestone will be added to the chronicle of biblical translations: the publication of The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (Vol. 3) (W.W. Norton) by Robert Alter. It is the first-ever all-English translation of the entire Hebrew Bible by a single scholar. As Simchat Torah approaches, this year on October 1, it is a fitting time to welcome Alter’s contribution to the study of the Torah.

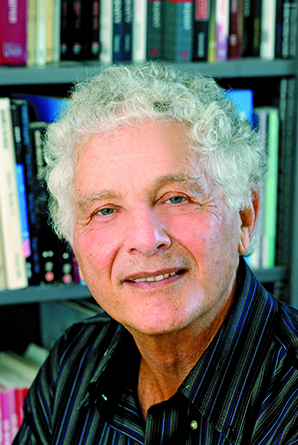

Robert Alter—Class of 1937 Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, where he has taught since 1967—worked entirely alone, consulting only his imagination and his formidable knowledge of literature. These influences were augmented by his lifelong devotion to the Hebrew language, both biblical and the revivified tongue of the modern State of Israel.

Long immersed in biblical studies—his 1981 book The Art of Biblical Narrative received the National Jewish Book Award for Jewish Thought—Alter labored on his translation for two decades. Brought to fruition in 5,000 pages in a beautiful three-volume boxed set, it is enhanced by footnotes that cite sources, explain word choices and offer perceptive, occasionally humorous insights into life—and love—in ancient Israel.

In a recent exchange, Alter, 82, shared his experience as an academic deeply committed to literature and a grandfather delighting in his young granddaughter’s commitment to the language of his heart. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What inspired this project?

My editor suggested that I edit and/or translate either a work on Franz Kafka, a writer about whom I have lectured extensively, or perhaps a book of the Bible. Just one book. My love of Hebrew and the opportunity to translate biblical Hebrew as I thought it should be translated persuaded me to choose Genesis. It was truly a labor of love that was both challenging and engrossing. That first volume was well received, so a second volume was commissioned. Soon, the project took on a life of its own. I worked book by book, completing the Five Books of Moses and then each book of the Prophets and the Writings.

Given the existence of many other translations, why did you undertake this project?

In my translation, I emphasize the intrinsically Judaic aspect of the text: I draw my commentaries from a wide range of sources that amplify and add dimension to the work. I also pay particular attention to the accuracy of the Hebrew. Given the

strong gap between English and biblical Hebrew, which is devoid of personal pronouns and exercises an economy of language, I had to develop a strategy to tighten the English rendition, to avoid polysyllabic and Latinate terms and to emphasize biblical syntax and rhythm.

Over the years, I have received appreciative letters and emails in response to my translation from an eclectic range of readers, including a church organist and a 14-year-old Jewish day school student.

Can you give an example of what you mean by “accuracy”?

In the 23rd psalm that begins “The Lord is my shepherd,” the King James translation of the concluding line reads: “I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” My translation reads: “I shall dwell in the house of the Lord for very long days.” The word “forever” is an abstraction, referring to God’s house in heaven. My translation, “for very long days,” refers to the Temple in Jerusalem. The Hebrew is more accurate, reality-based, easily understood and thus more relevant to contemporary readers and worshipers.

Given that you were born in America and attended public schools in Albany, N.Y., how do you explain your love of the Hebrew language?

I grew up during a vanished era of American Jewish life. Immigrants from Eastern Europe came from a multilingual society: Polish, German and Yiddish were all spoken, and Hebrew was another language to be mastered and used. That culture was incorporated into American Jewish life and led to the birth of Jewish camps that emphasized Hebrew. I attended a very good Hebrew school in Albany and had a post-bar mitzvah Hebrew education, but it was as a student at Columbia University and taking classes at the Jewish Theological Seminary that my love affair with the language, first nurtured at Camp Ramah, began.

I embraced the language, even making a naïve early effort to memorize every word in the Hebrew dictionary. I read the early Hebrew novels, Hayyim Nahman Bialik’s poetry and by 20, I was thinking and dreaming in the language, participating in a chug ivri, studying with great Hebraists. In short, Hebrew had become my life and I continued that immersion when I went on to doctoral studies at Harvard.

Do you favor any particular section of the Bible?

I consider the Book of Psalms the most magnificent poetry in any language. Of course, it is difficult to compare narrative to poetry. The resonance found in the Book of Job is awe-inspiring. The Jacob story is the first literary exploration of a multigenerational family. And, of course, the David narrative is unrivaled in its representation of political life and human nature. For me, it is an eternal mystery how that arid strip of land, ancient Israel, produced the miracle of a language of such richness, profundity of meaning and dramatic sweep.

How can the American Jewish community transmit love of Hebrew to its youth?

I deeply believe in Jewish day schools and Jewish camps. We are fortunate to have Israeli teachers who share their love of their native language with students in day schools, Hebrew schools and post-bar mitzvah classes. I would emphasize spoken Hebrew, even sung Hebrew. I’ll spare you my Hebrew rendition of “Popeye the Sailor Man,” which added choice words to my granddaughter’s vocabulary. Eight-year-old Dassi, who attends a Jewish day school in the San Francisco Bay area, proves my argument. Recently, I pointed to a loaf of freshly baked challah and wanted to teach her the Hebrew word for the knotted ends. “Neshikah,” she shouted before I could get a word in. She proudly explained that a neshikah, which means kiss, signifies both a beginning and an ending. Hebrew has already seeped effortlessly into her life. Is biblical Hebrew next? I hope so.

Gloria Goldreich’s latest book is The Bridal Chair.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply