Israeli Scene

Feature

On the Slow Road to Zionism

I have long bragged that I was born together with the State of Israel in 1948. But my first visit to the country was not among a group of idealists or smuggled as a refugee. Instead, I came for a two-week visit flanked by my parents on a scheduled El Al flight from Idlewild Airport in New York City. My crumbling leather travel diary memorialized the date: April 17, 1959. Middle of the At. Ocean. Weather: Fair. I wrote in a stilted self-conscious style, parroting what I imagined was expected: I plan to take many pictures and absorb many new things. Still, candor crept in: Our stewardess is pretty except for her long nose.

I was a precocious 10-year-old—an only child—who believed everything good about the new state. I was also an American who loved Saturday morning television shows and Halloween, and I recited the Pledge of Allegiance. Ambiguities had yet to surface.

I brought a Nancy Drew mystery onto the plane, but my mother didn’t allow me to turn on the reading light. The trip on the propjet was impossibly long, 24 hours. I counted down my time of imprisonment, measuring the hours against the most punishing boredom I knew: a two-hour session of Hebrew school would have passed, I calculated, then two, then three.

We landed long past dark. My uncle waited by the wire exit fence with wilted carnations to reunite with the sister he had separated from 13 years before in post-war Europe, when as survivors their lives took different paths. I had helped pack the food cartons we regularly mailed to my uncle and his family, including Hershey’s cocoa powder and Maxwell House coffee.

I was woozy with fatigue, but we were driven straight to a welcome reception in Tel Aviv for my father thrown by people from Brest-Litovsk, his hometown, which was then part of Poland. He hadn’t seen them since the 1920s or ’30s when they had left for Palestine; all who stayed behind were murdered by the Nazis, I was told.

The glamorous Dan Hotel loomed over the seashore in Tel Aviv, but we stayed down the street at the Palace Hotel, a wild misnomer. Breakfast had no Corn Flakes or Rice Krispies, but the middle-aged waiter with a twinkle in his eye and formal, accented English told jokes—though his punch lines had to be explained to me.

Things I took for granted were missing. Tissues didn’t come in a box. Instead, individual pieces were cut off a thick roll barely soft enough for my nose.

Leaning over my peeling balcony two floors over HaYarkon Street, I spied a donkey pulling a peddler’s cart. The only donkeys I knew in New York City were in the zoo. Sent downstairs to play alone in Park London, I fled back upstairs in tongue-tied panic when someone asked me a question in Hebrew.

In Tel Aviv, my parents shopped for handicrafts and memorabilia along Ben Yehuda Street: filigreed silver work, hammered copper plates, finely carved wood sculptures.

I had to wait in boredom while my parents’ long-lost acquaintances from their pre-war lives came in droves to visit for afternoon tea.

But Israel was also full of adventures.

My uncle was our guide all over the country. Nineteen when the war broke out in his native Warsaw, he survived Russian labor camps to sneak across borders after the war. He smuggled his sister—my mother—into the British zone of Germany, where they spent a few months as displaced persons. My mother eventually went to North America, while my uncle boarded a clandestine ship for Palestine. Intercepted by the British, he was sent to a Cyprus detention camp for 10 months, landed in Haifa on the eve of Israel’s independence and was immediately drafted. At the recruitment center, he claimed to be an experienced sailor. Soon, he found himself part of Israel’s infant navy and spent Israel’s War of Independence on a patrol boat making the run from Haifa to Atlit.

He talked his way into the Hebrew University and became a phytopathologist—“A doctor for plants!” my mother proudly explained. My uncle unlocked his laboratory after hours and showed me how to look through a microscope. My travel diary reports: I saw a fungus.

My uncle drove us the length and breadth of the land in the big, old black Ford sedan that my father rented. Once the car overheated and its engine sputtered. We found ourselves at a transit camp full of tents. A man with raggedy children peeking around his side offered us buckets of water for the radiator but refused the payment my father pushed forward.

My uncle himself owned a motor scooter with a detachable sidecar to seat his wife and little daughter. It resembled a rocket ship in an amusement park; the roads were full of them.

A year earlier, my Hebrew school class had been shown a pile of postcards with images of pressed wild flowers. Each bore the name and address of an Israeli child offering to become a pen pal. Thus began my correspondence with Atalia from Kibbutz Givat HaShlosha in Petach Tikvah.

Now that I was in Israel, I was invited to the kibbutz as an overnight guest. I rode there seated behind my uncle on his scooter, for once imagining myself glamorous.

I spent the night at the kibbutz, sleeping near Atalia in the communal children’s house, which wasn’t that different from being in summer camp—except for the boys in the next room. Atalia’s parents, plump and smiling, wore wrinkled, baggy clothing. At their modest two-room, ground-floor unit I was plied with chocolates and raspberry soda. Squares of torn newspaper hung on a nail in the toilet; with relief I discovered an old Kleenex in my pocket.

Atalia’s family treated me as a visitor from a rarified world. When we sat barefoot on the grass playing checkers, Atalia’s father asked if it was the first time I had felt grass between my toes. I went to Atalia’s 12th birthday party and, for presents, her classmates brought armfuls of wildflowers they had picked as they made their way across the kibbutz fields.

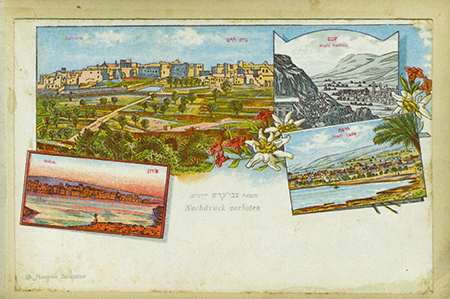

Every day of our trip we were introduced to another part of the country: an artists’ colony in Ein Hod, galleries in Safed, churches in Nazareth. I saw orchids at the flower show in Haifa. “Haifa!” I was told, “as beautiful as San Francisco!” As a child of Manhattan, the view from the Carmel Mountains down to the sea was magical in its splendor.

In the Negev, I duly noted in my diary Bedouin and camels, and the heart-stopping switchbacks of the new road winding down to Sodom. Swimming in the Dead Sea stung so terribly that I ran out in excruciating pain, too embarrassed to admit where it hurt. Even in my travel diary, I recorded: You don’t have to be afraid of crabs because nothing lives there.

On the road to Jerusalem, we photographed the red poppies growing between rusting tanks that had been abandoned during the War of Independence. (Much in Israel may have changed over the decades, but the mute testimony of the tanks is still there today.)

At a guesthouse on Mount Carmel, where the staff spoke only German, we ate varieties of homemade sour cream. A stop at the Sea of Galilee proved that it was not unlike familiar New England lakes—except for its squishy bottom and the absence of any safety rules—and in Akko, we had chewy pitas as enormous as pizza pies.

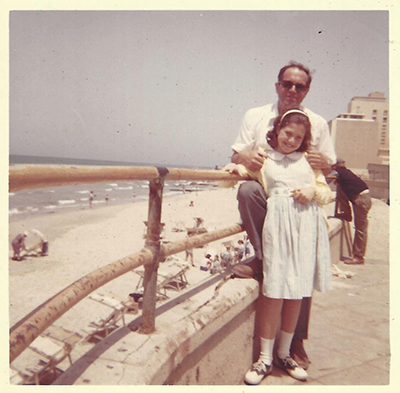

I look today at that photo of the girl with chubby cheeks posing next to the Crusader fort and the cannons planted by Napoleon in Akko. I wear an unflattering bucket hat called a kova tembel, an incongruous contrast to my baby blue, starched cotton dress with embroidered forget-me-nots.

I cannot truly recall the reality of Israel from my childhood, other than the riot of color and mystery, at once austere and exotic. What was a genuine impression and what had my memories distorted through the prism of time?

It seemed everybody I met in 1959 asked if I wanted to move to Israel, which I emphatically denied. I didn’t fall in love with the place until later. But a spark had been lit. My first entry in the travel diary ended in optimism: Many stars are out tonight.

My strong impressions eventually bloomed into aliyah. I returned time and time again until I settled down for good with my family, until it became as natural as if I had been there from the very beginning.

Helen Schary Motro, an American-born writer and attorney, has been living in Israel with her family since 1985.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply