Books

Personality

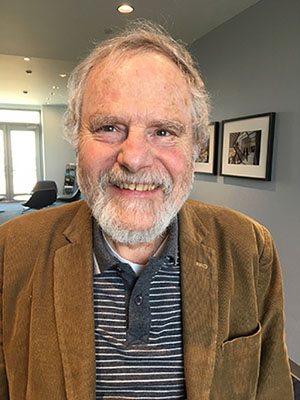

The Translator: Jeffrey M. Green

Jeffrey M. Green is an American-born translator who moved to Israel with his wife, Judith, and the first of their four children in 1973—two weeks before the start of the Yom Kippur War. Since then, the Jerusalemite has translated works by many renowned Hebrew writers, including S.Y. Agnon, Amalia Kahana-Carmon, Uri Nissan Gnessin and Aharon Appelfeld, the Holocaust survivor whose books depicted that catastrophic time through a child’s eyes. Green’s translation of Appelfeld’s final novel, The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping, came out in 2017; the author died in January. Green, 73, also translates from French into English and was recently an Olamot Center Visiting Scholar in the Jewish studies program at Indiana University in Bloomington, where this interview took place. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What was it like to work with Appelfeld?

I worked with him for about 30 years, so [our relationship] evolved a lot. He was around 55 when I first met him. He didn’t know English that well. Then he spent some time in Oxford and in Boston, so his English really improved. He wanted very simple language, very direct language in his books. He wanted everything to be in the present tense. In his opinion, present tense is direct. We had fights about it—he lost that one. I realize now that I had a good deal of resistance to Appelfeld. I was close to him, but I didn’t want him to inhabit me. You don’t want to be Appelfeld, with such traumatic Holocaust memories.

What are some things about translating books that might surprise people?

Translators are very focused on individual words and sentences. It’s very slow. Novels are meant to be read at a certain speed—if you read them too slowly, you’re not getting the right pace. I never read a novel that I am translating at the right pace.

Does that take some of the fun out of reading?

Yeah, but it’s not fun, it’s work. I also never read the book first before I translate—if I don’t know how it ends, there’s an incentive to keep going. People are always shocked that I don’t read the book first, but I’ve talked to other translators, and they don’t either. And once I finish a translation,

I don’t re-read it.

Are there aspects of translating Hebrew that are particularly challenging?

Hebrew is heavily imbued with Jewish culture. I remember Appelfeld described a funeral in one of his novels and said something about the kohanim having to stay outside the cemetery. How do you explain that to a reader who isn’t Jewish? Jews understand these references, but he wasn’t only writing for Jews.

You have compared your work as a translator to that of “the man following the elephant in a circus parade, gathering up the s—.” What did you mean?

In the end, it’s not about you. It’s similar to the role of an editor. He or she might have a major impact on the work, but it doesn’t say “edited by” on the cover. In The Translator’s Invisibility, Temple University professor Lawrence Venuti argued that the translator should “intrude” on the writer’s work. I think that’s dead wrong.

What are you working on these days?

I’m translating a book about 18th-century Jewish history. It’s a monster book. That’ll keep me busy for a while.

Jennifer Richler is a freelance writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Esther Hecht says

I wonder how Mr. Green resolved the issue of the kohanim having to stand outside the cemetery.

R.R. Brooks says

Green’s comment on the importance of reading novel at a certain pace is so true. As a novelist, I take it on my self to create that pace and appreciate the success of other novelists in achieving the elusive goal of changing pace in such a way as to never lose the reader.