Arts

Exhibit

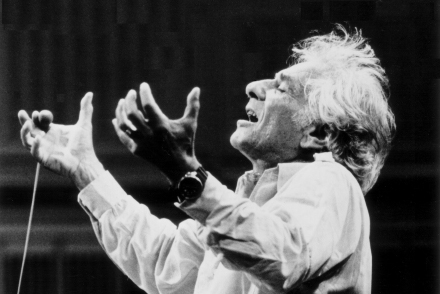

A Shofar Sounds in Leonard Bernstein’s Work

Some people remember where they were when John F. Kennedy was shot or when Neil Armstrong took his first lunar steps. I remember where I was when Leonard Bernstein died. It was October 1990, and I was on my honeymoon, crossing a traffic circle in Beaune, France, when my newly minted husband read the headline from the International Herald Tribune in shocked tones.

Like many music lovers, we found inspiration in Bernstein’s art but also in his life. Here was a musical polymath who proved it was possible to do it all. Bernstein was the principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic, a noted Gustav Mahler expert and the charismatic presenter of the Omnibus series and Young People’s Concerts on CBS television. He also composed symphonies, chamber music, ballet and film scores, choral works, operas and a cache of musicals, including one of the most beloved of all time—West Side Story. But Bernstein was more than just a towering American musical presence who happened to be Jewish. He used music to actively explore his Jewish identity, further the cause of social justice and search for a solution to what he called the 20th-century crisis of faith.

These elements of his life and work provide the foundation of “Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music,” a traveling exhibition that premiered at Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History in 2018, part of the centennial celebration of the great musician’s birth, and is now at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland through March 1, 2020. Through listening stations, films, interactive media and personal artifacts, the exhibition offers a multi-layered appreciation of Bernstein’s work as it relates to the Jewish experience.

Bernstein was born on August 25, 1918, to Samuel and Jennie Bernstein, Ukrainian Jewish immigrants who settled in Lawrence, Mass. His earliest exposure to music was at Congregation Mishkan Tefila, a fairly progressive Conservative synagogue that featured a mixed choir, organ music and a Vienna-trained cantor.

“Bernstein, in looking back on his life, many times would point to the music he heard there as ‘the first real music I ever heard,’ ” said curator Ivy Weingram. “He was overcome with emotion when he’d hear the choir, cantor and organ thundering out. That was when he first realized music was his raison d’être.”

Bernstein was committed to bringing the culture and language of the Jewish people to a wider audience. His “Chichester Psalms” is one of the most performed Hebrew choral works in the world, and two of his three symphonies incorporate Jewish musical and textual themes. Symphony No. 1 “Jeremiah,” which includes a setting from the Book of Lamentations for mezzo-soprano, paraphrases the haftorah trope. For Symphony No. 3 “Kaddish,” Bernstein took the unusual step of adding narration, incorporating his own, somewhat controversial text that challenges God to explain his relevance in a world with so much pain. He then explores the answer in music. Even his musicals contain covert references to his Jewish identity: The Jets’ call that opens West Side Story (“da-daaa-DAH”) simulates the call of the shofar, and he repeats this sound in the overture to Candide.

“We’ve developed a custom, signature interactive piece that allows visitors to explore the thematic origins of Bernstein’s music, regardless of one’s musical background,” said Weingram. “We take a sampling of his work and break it down into layers, with a little performance or a bit of the score. So, we’ll watch someone blow a shofar, and then turn a block and hear just that snippet of the Jets’ call. Or we’ll hear a cantor reciting the Kaddish.”

Of all Bernstein’s compositions, the one that most directly reflects his struggle to come to terms with the burdens of the 20th century is MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers, which forms a centerpiece of the exhibition. MASS is one of the first true crossover pieces, integrating pop, rock and classical music into the setting of a Roman Catholic Mass. While that may seem a surprising choice for a Jewish composer and his Jewish lyricist, Stephen Schwartz, it resulted from a commission by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to open the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., in 1971. MASS memorializes the country’s only Catholic president and questions how one can still believe in God in the face of war and violence.

“It was during the Vietnam era, and Bernstein saw so much tragedy, violence and the complexities of American military intervention abroad,” said Weingram. MASS’s main character, known as the Celebrant, a Catholic priest conducting the ritual, begins the piece with his faith intact. Over the course of two hours, a rowdy street chorus attempts to spiritually break him down. “We can see Bernstein as the Celebrant in that moment,” posited Weingram, “feeling like the world has shaken his faith in God, humanity and our nation’s leaders.” MASS is slated for several productions this year, including in Kansas City, Mo., and Orlando, Fla.

In the exhibition, an immersive film plays on a curved surface in a chapel-like gallery, surrounding the viewer with a combination of video selections from MASS and still images of Vietnam, Martin Luther King Jr. and anti-war protests. The projections transition to subsequent examples of Bernstein’s musical activism, including his famous 1989 Christmas concert celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall. Bernstein assembled an international ensemble for a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 that substituted the word “freedom” for “joy” during the “Ode to Joy.” The concert was simulcast on screens along the main thoroughfare next to the wall, and Berliners listened as they chiseled away at the structure and traversed the city freely for the first time in 28 years.

The film concludes with recent examples of musicians confronting injustice. It describes how, for instance, when riots broke out in Baltimore in 2015 after a 25-year-old black man, Freddie Gray, died in police custody, the city imposed a curfew, forcing the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra to cancel its evening concerts. Conductor and Bernstein protégée Marin Alsop took the orchestra outside during the day, invoking Bernstein’s credo: “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

Among the more than 100 artifacts on display are Bernstein’s tuxedo and baton, one of his pianos and Judaica from his private collection, including a Talmud handed down from his father, who was descended from rabbis.

If the museum’s mission is to tell the story of how Jews have shaped and are shaped by the American experience, Leonard Bernstein is the perfect subject.

“He went to Boston Latin School, Harvard, the Curtis Institute of Music, he became director of the New York Philharmonic. He was grateful for the freedoms he could have as a Jew in America to reach the highest levels of culture and society,” said Weingram. “And at the same time, he walked a very fine line between presenting himself as the quintessential American and being true to his Jewish heritage. Perhaps his greatest gift was knowing music could bridge the many pieces of his identity.”

For information on other centennial events, including concerts and films, go to leonardbernstein.com.

Joanne Sydney Lessner is the author of the novel Pandora’s Bottle and writes reviews and features for Opera News and ZEALnyc.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply