Israeli Scene

Feature

An IDF Program for Teens on the Autism Spectrum

In the nerve center of the Israel Defense Forces known as The Kirya, 10 soldiers are sitting in front of computer screens perusing aerial photographs.

There is nothing especially noteworthy about the sight of these recruits at work in an intelligence unit inside this sprawling Tel Aviv base. Which makes the scene all the more remarkable, since all of the young men are on the autism spectrum.

The 10 are among a growing number of Israelis being trained to serve in various units of the IDF despite a diagnosis that usually means an exemption from any sort of military service. The young men and a few women are doing so thanks to a pioneering program called Roim Rachok. Loosely translated as Seeing Beyond, the program began in 2013 and to date has enabled some 90 soldiers on the spectrum to serve in the IDF.

Roim Rachok is believed to be the only program in the world designed to integrate autistic people into the military. It includes a six-month pre-army training course, three months of which are spent in an IDF unit on a trial placement.

One of the new trainees in this intelligence unit, Private Tom—his name and those of others in the article have been changed in compliance with IDF protocol—is a lanky, dark-haired 19-year-old with a direct gaze. He was in a special track for students with communication problems at the high school at his moshav near Beit Shemesh. “It was hard to integrate socially in high school—others weren’t that tolerant of those who don’t fit the norm,” he says.

Along with communication difficulties, Tom recalls something else that always set him apart: sharp visual awareness. “I would notice whenever someone moved an object at home from one place to another—or see a tiny bug on the ground that no one else saw. I never thought that this would come in handy. But look,” he says, grinning, “here I am.”

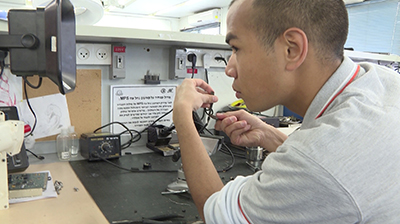

“Here” is the aerial reconnaissance unit, where he and his fellow trainees are working alongside official inductees, scrutinizing satellite and other images, searching for minute changes that could provide critical intelligence for the IDF.

The fact that many people on the spectrum possess exceptional visual acuity and excel at detail-oriented work was one reason why Leora Sali believed they could be a valuable resource for the army, particularly in aerial reconnaissance’s Unit 9900.

“I knew this had potential because it taps into their strengths,” says Sali, a co-founder of Roim Rachok, who understood this from her own experience as the mother of a son on the autism spectrum. She had spent decades working in security when she was approached by a colleague, former Mossad chief Tamir Pardo, with the idea of utilizing the special abilities of autistic individuals to meet Israel’s security needs.

Sali then raised the idea with the director of Unit 9900, whose soldiers are tasked with examining countless images to spot minute changes. He told Sali that he has had difficulty finding soldiers who could do such challenging work and stick with it, since many soon get bored with its repetitive nature. Sali saw a potential win-win situation—as did the program’s other founder, Tal Vardi, a retired security official.

But it was clear to both Sali and Vardi that possessing exceptional visual abilities would not be enough for people on the spectrum to integrate into this or any other unit in the army. “The IDF,” says Sali, “doesn’t know how to deal with disabilities of this kind”—which is why those on the spectrum, even high-functioning individuals, are usually exempted from compulsory military service.

He two realized that in order to ensure a positive, productive experience for both sides, they needed a partner to train the recruits as well as their IDF commanders, who may not have dealt with autistic individuals before.

They found that partner in Ono Academic College, a post-secondary institution with a strong health studies program based in Kiryat Ono, on the outskirts of Tel Aviv. Working together, the IDF and the founders designed the intensive pre-army training program—three months at the college followed by three months at a base—that would not only teach the recruits satellite analysis and other military tasks, but also basic life skills.

In the first three months, a team of speech therapists, occupational therapists and psychologists instruct the recruits on how to communicate with a commander, make a presentation in front of a group, write a polite email and even how to travel by bus (many have never done so on their own).

Sali recalls one soldier who spent several hours preparing a detailed summary of a topic, only to present it to the audience with his back turned to them. “It took a month and half to teach him to do it differently,” she says, “but he did.”

“There is a big gap between the cognitive abilities of these soldiers and their social abilities,” says occupational therapist Efrat Selaniyko, Ph.D., the professional manager of Roim Rachok. “They can understand algorithms, but often lack basic social understanding.”

The Ono team also coaches the commanders in the program—people like Corporal Hagar, who is in charge of the new recruits now placed with Unit 9900.

“Before I came here, I was really ignorant—for me, autism and intellectual and developmental disabilities were the same thing,” she admits. “But once I began working with them, I saw that they were very intelligent, just that their brain works a little differently. They tend to see things in absolute terms—black or white. So if I would say, ‘Come back here around 4:15,’ they didn’t know what to do. But if I said, ‘Come back here at exactly 4:15,’ they would say, ‘O.K.,’ and be back on time.

“I’ve learned to adapt and explain myself in different ways,” adds the 20-year-old commander, who is effusive about the advantages these soldiers bring to the job.

“They are attentive, have a long concentration span and are highly motivated,” she says. “They were thrilled just to put on a uniform. They can sit in front of a computer screen and work intensively—they don’t have coffee and gossip with a friend like other soldiers often do.”

If the participants successfully complete their six-month training, they can join an army unit and serve alongside soldiers who are not on the spectrum. For most of them, it is nothing short of a transformative experience.

Tom, who is close to completing the pre-army program, says his training and experiences in the IDF have allowed him to turn over a new leaf. “I have had a chance to lead,” he notes. “I have many good friends and I feel like I am doing something meaningful by contributing to the country.”

Sergeant Shlomi, a Roim Rachok graduate, sits next to Tom in The Kirya. He agrees that service has changed him. “I came in one person and I am leaving as another,” says Shlomi, who is nearly finished with his 32-month service, the standard for Israeli men. “When I first got here I was really quiet. I would just sit on the sidelines and watch. Then I tried to fit in. One of the guys I work next to said that he would never have guessed I was on the spectrum if I hadn’t told him. I feel like I am among equals here.

“And now that I have this experience, I try to help guide new people in the program,” continues the stocky, sandy-haired 21-year-old from Ra’anana as he exchanges a look with Tom and high-fives him.

The impact the program has on soldiers’ lives goes beyond their military service. “After learning in the course how to manage with public transportation, one participant showed up at his grandmother’s door for the first time on his own. They were both delighted,” says Sali. “Suddenly parents see their children flourishing not just in the army, but in life—they are more independent.”

ccording to shlomi’s mother, Lenore, the program has been “unbelievable” for her son. After he was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome in junior high school, “we were very afraid of what he would do after high school,” she says. “Would he be able to take care of himself? How would he fit in?”

Through Roim Rachok, he learned a profession that he excels in—aerial and satellite analysis—and has even represented the program at public events. “That’s something,” his mother says, “that was unimaginable before.”

Other Roim Rachok graduates have also represented the program in public ceremonies. In 2016, Dan Korkovsky, a member of the first Roim Rachok course, was chosen by the IDF to be an official torchbearer for the annual Independence Day ceremony on Mount Herzl.

The involvement of Roim Rachok continues even after the soldiers complete their service. Program leaders are now helping Shlomi find work in the civilian sector in a position similar to the one he held in the army. Other graduates have continued to work in the army part time while taking courses at university.

“A number of companies have expressed interest in hiring our graduates,” says Sali.

Until recently, only recruits who live in the center of the country could join, since the program operated solely on bases located in or around Tel Aviv. But thanks to the aid of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Beit Ekstein, an organization that provides housing, education and employment for those with disabilities, Roim Rachok got an apartment near Ono college for participants who live in other parts of the country. A second apartment will be available shortly.

Aside from grants from Israel’s National Insurance Institute and Ministry of Social Affairs, the lion’s share of the program is financed through private donations.

The success of Roim Rachok in Unit 9900 led to its expansion into other army units. Now, in addition to deciphering aerial and satellite photos, there are also tracks in software quality assurance, information sorting, electro-optics and various tasks in the air force. With the increase in individuals diagnosed with some form of autism—in Israel, it was in one in 2,000 two decades ago, whereas today it’s one in 100, according to a 2016 Welfare Ministry report—Sali is convinced that the need for Roim Rachok will only grow.

Because of careful screening, about 90 percent of those who are selected for the program complete the six-month training and go on to serve successfully in the army. Those applying must be Israeli citizens, know Hebrew and be able to converse. They must also be aware that they are on the autism spectrum. Most are considered fairly high functioning.

Sali’s own son, now in his 20s, was enrolled in the course but did not go on to serve in the army. “He didn’t continue because it became clear that it wasn’t suitable for him,” she says. “There were emotional problems. I first became involved in this out of personal motivation, but I have moved on to a broader goal—to do something that has an impact on others.”

Those others include not only soldiers on the autism spectrum, but their commanders and society as a whole.

“Commanders have told me that working with autistic soldiers has made them better commanders and better human beings,” says Sali. “They say they are better able to accept others, with their strengths and weaknesses, and develop more patience and sensitivity, which affects their relationships with all soldiers, not just the ones on the spectrum.”

She recalls what one mother told her: “It’s not merely that you saved one soul, but that our extended family and even our neighborhood are affected by this. He comes home in a uniform—our boy who is on the spectrum, serving in an elite intelligence unit—and it’s a sort of statement, a declaration.

“There is a ripple effect,” says Sali. “It’s a change in Israeli society. We’re part of that.”

Leora Eren Frucht is an award-winning journalist who lives in Israel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Ana Kerner says

Thank you for sharing this story! Because of a head injury I had as a young girl I see the world through different eyes too. Though I am healed mentally now, at age 64 I have a passion to help those people who have a difference, like I did. This story is a wonderful example of accepting people as they are and using their gifts.