Israeli Scene

Feature

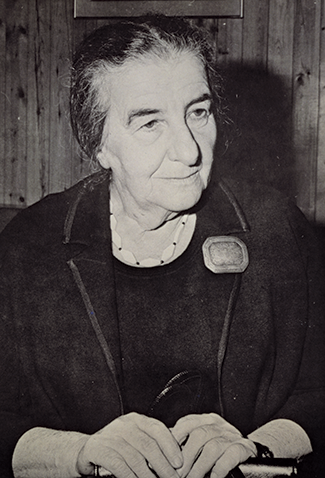

Golda: A Force of Nature

Golda Meir, the fourth prime minister of Israel, was a woman of many contradictions. The Russian-born, American-raised Golda was single-minded in her dedication to Zionism and tough as steel in demanding her way. An irate stare from her could wither the strongest official and her disapproval could send fear through the hearts of seasoned politicians. She could also be everyone’s loving grandmother. Her charm, when turned on, disarmed the most antagonistic adversary; her homey anecdotes spread an aura of warm camaraderie. A dyed-in-the-wool socialist, Golda developed tight friendships with wealthy American Jewish capitalists. Poorly educated, she nevertheless mesmerized audiences with her speeches, most of them unscripted. The ultimate insider—she had been labor minister as well as foreign minister before becoming prime minister—she was also an outsider: a woman reaching for the highest leadership roles in a male-dominated society.

Her struggle to secure her place in Israel’s political upper echelon led to other contradictions. She opposed organized feminism and would not acknowledge that she herself had experienced discrimination because of her gender, although from her youth onward she had. On the other hand, that she refused to be identified by gender reinforced one of feminism’s ultimate goals: She bridled at being referred to as a woman minister. She did not become prime minister in 1969 because she was a woman, she maintained, but because she had the support of the majority in the Knesset. And her achievements, despite formidable obstacles, inspired women everywhere.

The following feature is adapted from the newly published Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel by Francine Klagsbrun.

After the United Nations voted in 1947 to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, Great Britain prepared to give up its mandate over Palestine, while the Arab League, composed of the surrounding Arab nations, prepared to wage an all-out war against the Jewish state. Right before that vote, in November 1947, Golda, then head of the Jewish Agency political department in Jerusalem, had met with King Abdullah I of Jordan. At that time, Abdullah gave his word not to attack the Jews if the vote went through. He made it clear, however, that he intended to take over the West Bank after partition. They met in the northern village of Naharayim, a strip of land that borders Israel and Jordan.

But in May 1948, with war imminent, Golda wanted to meet with the king again to make sure he would keep his word to stay out of the conflict that was brewing.

Fearful of other Arab leaders, Abdullah agreed to the meeting reluctantly and on condition that Golda go to him in Amman. After conferring with David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv, she went on to Haifa, where Ezra Danin—an Arabist who later became an Israeli intelligence officer—joined her. From there, Danin and Golda began a long, hazardous trip. Danin asked her why she was taking the risk, because the mission would probably fail. “If there is the slightest chance of saving one Jewish soldier, I’m going,” she answered, and they pushed on. In Naharayim, Danin donned the traditional headgear of an Arab man. Golda disguised herself as an Arab woman in a long black dress and veil. The pair would appear as husband and wife for the benefit of Arab legionnaires, as Jordan’s soldiers were called, who lined the borders between the two lands. Muhammad Zubati, the king’s close confidant, arrived after dark to drive them to Amman. On the way, they were stopped at least 10 times while legionnaires checked their identity and Zubati called out his name to carry them through.

In Amman, Zubati took them to his home in a car whose windows had been covered with heavy black fabric. The king received them there in a friendly manner, but to Golda he seemed different from the person she had met several months before—pale, depressed, tense. He had sent a proposal in advance of what he wanted: Palestine would remain undivided, and the Jews given autonomy in the areas they inhabited. At the end of a year, the entire country would be merged with Jordan under Abdullah’s rule, with a single parliament in which Jews would have 50 percent of the seats.

Abdullah declared right off that the only way to avoid war was to agree to his offer, and Golda indicated immediately that it could not be accepted. Why, he wanted to know, were the Jews in such haste to declare an independent state? A people who had waited two thousand years could hardly be described as hasty, she answered. She reminded him of the agreement they had made and of their many years of friendship. “We are your only friends in the Middle East,” she said.

The king did not deny that he wished to keep the agreement, but things had changed. “Then I was alone, now I am one among five,” he said, referring to the nations preparing for a conflict—Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon. “I have no choice, and I cannot act differently.” When Golda pointed out that if there had to be war, the Jews would fight with all their strength, Abdullah agreed that the Jews would have to resist any attack. When he suggested a meeting of moderate Jews and Arabs to discuss his proposal, Golda rejected the idea out of hand. Not even “10 responsible Jews” would support his plan, she said. If, in fact, there was to be a war, the Jews would win it, and perhaps they could meet again after the Jewish state existed.

Despite the hard words, the rest of the conversation remained friendly. Abdullah bade his guests farewell and left. Sick at heart, knowing war was inevitable, Golda wanted to leave immediately, but Danin advised that refusing the bountiful dinner arranged for them would insult the king. She dutifully heaped her plate full and barely ate, and the two left as soon as feasible. It was near midnight, Monday, May 10, 1948. From their car window, as they

drove through a Jordanian military camp, they saw Iraqi forces preparing to invade Palestine.

Their Arab driver, frightened by all the checkpoints, dropped them off on the Jordanian side of the border, about two miles short of their destination in Naharayim. They groped their way in the dark through dangerous Arab territory until, about three in the morning, they met up with a scout from the Haganah, the Jewish underground army, who led them to Naharayim.

With little rest, Golda headed from there to Tel Aviv and a meeting of the Mapai Party’s central committee. As she entered the room, Ben-Gurion looked up expectantly. Rather than interrupt the meeting, she scribbled a note and handed it to him. “We met in friendship,” she wrote. “He is very worried, and he looks terrible. He did not deny that there had been talks and an understanding between us…but now he is only one of five.” She could barely look at Ben-Gurion’s face as he read. He understood that the last shred of hope that the king would refrain from war had vanished.

According to Moshe Dayan, Israel’s military leader, after their meeting Abdullah forever bore a grudge against Golda. She had placed him in an impossible position, the king said, by giving him the alternatives of either agreeing to an ultimatum that came from the lips of a woman or going to war. In such a situation, he had “of course” to take the second option.

True, Abdullah would probably have felt more comfortable with a Moshe Sharett or Eliyahu Sasson, men who knew the Arabic language and Arab culture. But Golda’s refusal reflected the thinking of the nascent country’s leadership: Neither Ben-Gurion nor Sharett, nor any other Jewish leader, would have agreed to the king’s terms. In fact, Ben-Gurion dismissed a last-minute appeal to him from Abdullah to accept his proposal before declaring a state. Nothing Golda said, or who she was, led the king to join with the Arab League against the Jewish state. Intense pressure from other Arab leaders and the Arab public drew him into battle. Blaming Golda was a cheap excuse.

Although not a member of the Administrative Council—the provisional government set up in preparation for declaring a state—Golda had been invited to its meeting to report on Abdullah. She accurately summed up the king’s situation: “He is going into this matter [the war] not out of joy or confidence, but as a person who is caught in a trap and can’t get out.”

Three of the 13 council members were absent. The 10 who were present, as well as guests like Golda, sat around a large square table in the Jewish National Fund office building in Tel Aviv. The discussion soon turned to the most crucial subject at hand: whether to declare a state as soon as the British left.

Hesitation and anxiety gripped the group. Moods and statements swung from one extreme to another, often in the same person—joy at freedom from British rule, fear of the looming Arab invasion. For the first time, there would be no third party to act as a buffer between Jews and Arabs. The questions of when and how to proclaim the state had been agonized over for months, but now the moment of truth had arrived.

“It is doubtful that a quorum of 10 Jews was ever before summoned to determine the course of Jewish history in such a manner,” one observer wrote.

Ben-Gurion called on the heads of the Haganah, Yigael Yadin and Israel Galili, who were in attendance, to assess Arab strength versus Jewish. “At this moment I would say that our chances are 50-50,” Yadin said. “To be more honest, I would say they have a big advantage.” It was a daunting statement.

Perhaps, some members argued, they could stop short of actually proclaiming the state, find a compromise and announce an interim position. Golda disagreed.

“We cannot zigzag,” she told her colleagues. Once they decided to create a state, they could not go partway. They had to follow through fully, with “every detail of the details” in place. “This is what the world is waiting for,” she said. Since she was not on the council, Golda could not vote, but her outspoken support for statehood helped sway others. Six of the 10 members voted for declaring a state.

The British were scheduled to leave at midnight on Friday, May 14, 1948. The state would be proclaimed that afternoon so that no gap in governing existed. Ben-Gurion insisted that Golda return to Jerusalem on Thursday to confer for a final time with the British High Commissioner and remain in the city. It broke her heart to have to miss the ceremony establishing the state that was to take place in the Tel Aviv Museum. The two-seater Piper Cub plane that would carry her to Jerusalem was scheduled to return immediately with Yitzhak Gruenbaum, slated to become minister of interior in the new government. Soon after the takeoff from Tel Aviv, the plane developed severe engine problems, forcing the pilot to turn back. With the engine almost gone, he landed in Tel Aviv. And that is how Golda was in Tel Aviv to sign Israel’s Declaration of Independence while Gruenbaum remained in Jerusalem.

Golda washed her hair and put on her best dress for the ceremony. A car and driver took her to the museum. Although the time and place of the ceremony had been kept secret for security reasons, word leaked out, and at least half the city thronged outside. At exactly four o’clock, the ceremony began. Ben-Gurion rapped his gavel, and the more than two hundred guests rose spontaneously and sang “Hatikvah.”

“I shall now read to you the Scroll of the Establishment of the State,” he began softly. His voice rose slightly as he read the 11th paragraph ending with the words “We hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael, to be known as Medinat Yisrael, the State of Israel.” Almost as one, the audience rose again, clapping, singing and sobbing with joy and excitement.

After the entire proclamation was read and adopted, signers walked to the desk one by one in alphabetical order to write their names on a sheet of parchment. Golda’s hands shook and tears poured from her eyes as she signed “Golda Meyerson” (her married name). She thought about the signers of the American Declaration of Independence she had learned about as a child and about her journey from her birthplace in Russia to this land, and she couldn’t stop weeping. That evening, she and two colleagues went to Ben-Gurion’s home with a bouquet of flowers to congratulate him for all he had done to make this day happen.

When asked in later years what her most important day in Israel was, Golda replied without hesitation, “Friday afternoon, when the state was declared. It was the greatest moment.”

Golda, the Lover

Separated from her husband, Golda was involved with David Remez, her mentor and lover, for many years. He was jailed by the British in 1946 along with other leaders of pre-state Israel suspected of hiding arms. Her letters to him, in Hebrew, reveal her warm and passionate side.

“Do you know how dear you are to me?” she asked in her letter of September 25, 1946, the eve of the Jewish New Year. “Do you have any clue about all the things in my heart? It seems to me that if we were to meet now, I would say everything to you.”

She had sent him a book of poems that she hoped would express her feelings better than her own words. For her, she wrote, “every word of yours, every letter is holy to me.” She compared Rosh Hashanah to another holiday, Passover, which the two had spent together. “How good it was for me then. We were together. Day after day, hour after hour, night after night. I look forward to that.”

She ended with the same loving sentiments: “If only a shred of what is in my heart reaches you today, it will be a small part of the contents of my wishes for a good year.”

Adapted from Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel. Copyright © 2017 by Francine Klagsbrun. Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply