Arts

Exhibit

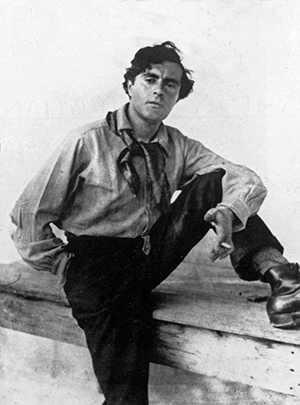

Revealing the Real Modigliani

“Modigliani Unmasked,” at Manhattan’s Jewish Museum from September 15 through February 4, 2018, could not be timelier. It’s the first exhibit—another will open at the Tate Modern in London in November—leading up to the centennial of Amedeo Modigliani’s death in 1920 at 35, of tubercular meningitis. The great Italian artist’s fame has skyrocketed, as has the market value of his work. This elegant exhibition, curated by art historian Mason Klein, explains why.

The 150 drawings, paintings and sculptures on display from Modigliani’s early years in Paris bring into sharp relief the fact that Modigliani was a multiculturalist even before multiculturalism existed.

Part of that attitude, as explained in “Modigliani Unmasked,” was due to his upbringing in Livorno, Italy. The city was a cultural melting pot where Jews were welcomed, and the artist himself was steeped in the universalist traditions of his cosmopolitan Sephardi family.

Modigliani arrived in Paris in 1906, the year Alfred Dreyfus was vindicated. But anti-Semitism lingered, intensified by an influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, including artists such as Marc Chagall and Chaim Soutine. Unlike those other artists with their thick foreign accents, Modigliani, with his Italianate panache and fluent French, could have “passed.” He chose not to and famously went around Paris proclaiming his Jewishness.

“The exhibition addresses the importance of the artist’s audacity in defining himself as different,” Klein said in an email. “His embrace of his Jewish otherness, at a time of intense xenophobia and anti-Semitism, was deliberate and self-affirming.” Although direct references to Judaism are rare in Modigliani’s art, he makes his Jewish heritage explicit in two paintings in the exhibition—The Jewess, an early portrait, and Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, which incorporates Judeo-Christian symbolism.

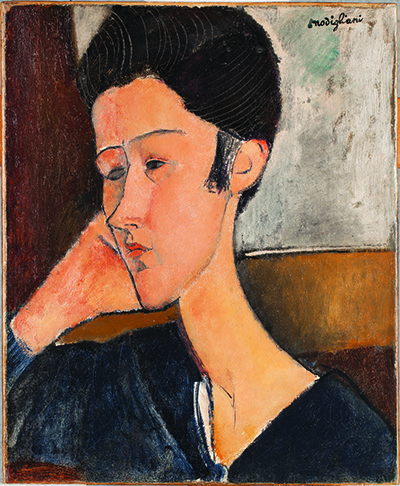

Modigliani’s distinctly global worldview, however, is apparent everywhere in these early pieces. Like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and most of his peers, Modigliani fell under the spell of the non-Western works shown in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, the first anthropological museum in Paris. But his use of those influences—African, Egyptian, Middle Eastern—was unique and apparent in the long, narrow noses; oval faces; and almond-shaped, often opaque eyes of his portraits. He did more than just appropriate exotic forms in the service of style (as with Picasso and Cubism); he absorbed their diversity into a multicultural vision and recreated the art of portraiture for a diverse and complex world.

This vision is meticulously spelled out in this exhibition, most literally in the elongated shapes in iconic paintings such as Portrait of Hanka Zborowski and Portrait of Lunia Czechowska as well as through a series of drawings of heads—some spare, some adorned with elaborately arranged hair and jewelry—that reflect his developing style.

A selection of beautiful drawings of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, with whom he had a passionate friendship, reveals her as another source of inspiration. Tall and gazelle-like, with an aquiline profile, she was his vision incarnate. Akhmatova, in turn, was inspired by Modigliani’s embrace of all cultures, all peoples—an attitude we could use more of these days. It reverberates throughout this exhibition, casting off the sensationalized, romanticized Modigliani legend and revealing the compassionate, idealistic man behind his timeless art.

Elin Schoen Brockman writes about art and travel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply