Israeli Scene

Feature

The War that Changed Everything—for Israel, for Me

I was a 13-year-old boy living in Brooklyn, N.Y., when in May 1967, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser blockaded the Straits of Tiran, Israel’s southern shipping route, and declared the imminent destruction of the Jewish state. At night, I would watch the news on television with my father, a Holocaust survivor. Crowds in Cairo and Damascus waved banners imprinted with skulls and crossbones and chanted “Death to Israel.”

That was the first shock—genocidal Jew-hatred had survived the Holocaust. Don’t worry, my father reassured me, we’re not alone. France, after all, was Israel’s closest ally in those years. But then, at our most desperate moment, France abruptly turned against us. Of course, “us.” Those days transformed me into a surrogate Israeli. Faced with the possible destruction of Israel, many American Jews suddenly realized how essential Israel’s existence was to their own sense of place in the world, just how unbearable another Jewish destruction would be.

But America remained neutral. Mired in an unpopular war in Vietnam, President Lyndon B. Johnson—one of the most pro-Israel presidents until that point—decided not to risk involvement in another conflict. Meanwhile, Nasser formed a military pact with Syria and Jordan, and ordered United Nations peacekeeping forces out of the Sinai Peninsula. Astonishingly, they packed up and left—without so much as a debate in the Security Council. Israel was left exposed and alone, forcing it to make a pre-emptive strike against Egypt on June 5.

The trauma of isolation in May 1967 imprinted on Israelis a permanent wariness toward international guarantees. Not the United Nations, not the European Union, not even the United States can ultimately be trusted to protect Israel; only Israel will protect itself.

The events that year united Jews around the world in an emotional trajectory—from existential fear to relief when Israel pre-emptively struck to euphoria at the extent of its victory. It was, in its way, a replay of the emotional intensity of the 1940s, when the Jewish people went from the abyss to rebirth.

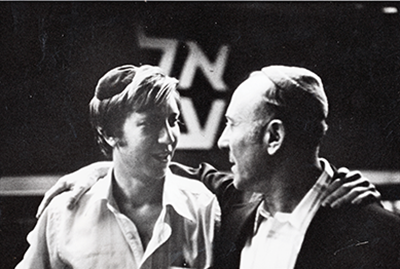

Three weeks after the war, my father and I flew to Israel. Travel to Israel was so unusual then that my friends all came to see me off at Kennedy Airport—and were there to greet me when I returned. Israel was filled that summer with tourists from almost every part of the Diaspora. In fact, mass tourism to Israel began with the Six-Day War. Jews simply had to be there, to touch Israel’s radiance.

At the Kotel, my father made his peace with God. After the Holocaust, he had rejected religion; God, he said, didn’t deserve Jewish prayer. It was a very Jewish response. My father didn’t stop believing in an all-powerful God—which was precisely why he was angry with Him. God could have stopped the Holocaust but chose not to. Now, though, with the magnanimity of a victor, my father could forgive God and pray again.

It was a time of restoration. the state of israel before 1967 lacked a single significant Jewish holy site. (The major sites of Christianity, by contrast, are mostly within the pre-1967 borders.) But suddenly, here were Abraham and Sarah in Hebron, Rachel in Bethlehem, Samuel the Prophet in Ramah. My father, whose parents evaporated in Auschwitz, now had access to ancestral graves.

It was a time of restoration for lost Jewish tribes. The three million Jews sealed behind the Iron Curtain and subjected by the Kremlin to forced assimilation suddenly awakened from amnesia and rejoined the Jewish people. Young Soviet Jews began taking pride in an identity they knew almost nothing about. Natan Sharansky, the prisoner of conscience-turned-Israeli politician, would write years later that he was thrilled to hear that Israel had conquered the Temple Mount, though he didn’t know what the Temple Mount was. Over a million former Soviet Jews now live in Israel, a direct consequence of the Six-Day War.

In 1982, I, too, moved to Israel. Having discovered 15 years earlier how essential a Jewish state was to my life, I could no longer keep away. I live in Israel because it exists.

But the Six-Day War—in which Israel reunified Jerusalem and captured the Sinai, Golan Heights, Gaza Strip and West Bank—also bequeathed to us wrenching dilemmas that would have once seemed inconceivable to my father and his fellow survivors. How do we reconcile power and morality? How can we continue to rule over another people and risk Israel’s ability to remain both a Jewish and a democratic state? And yet how can we return to the pre-1967 borders, merely nine miles wide at their narrowest point, and risk vulnerability in a disintegrating Middle East? How do we choose between the nightmare of an endless status quo that leaves Israel as a permanent occupier of a hostile population and the nightmare of an independent Palestine that could well become yet another radical and destabilized Arab state—minutes from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem?

This year, on the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, I will suspend the debate about settlements and occupation and security and peace. For one day, I will celebrate our survival, the persistence of our dreams. And I will feel grateful for being part of the generation that returned to Jerusalem.

Yossi Klein Halevi is a senior fellow of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, where he co-directs the Muslim Leadership Initiative. He is the author of Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation.

For more of our coverage of the Six-Day War 50 years later, please read:

Six Transformative Days: A Primer on the Last 50 Years

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply