Israeli Scene

Feature

Six Transformative Days: A Primer on the Last 50 Years

The 1967 Six-Day War transformed Israel and the Jewish people. It is impossible to understand the postwar reaction—and repercussions—without knowing the dramatic events of May that led up to the June war. The Soviet-backed Egyptian leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, had unified the Egyptian, Jordanian and Syrian militaries under the United Arab Command, declaring “our basic objective will be the destruction of Israel.” He expelled the United Nations buffer force between Egypt and Israel in the Sinai Peninsula and blocked the international shipping routes to Eilat in the Straits of Tiran, both considered acts of war under international law. Mobs gathered in Arab capitals shouting, “Death to the Jews.” Many around the world spoke in hushed tones about the possibility of a second Holocaust.

When Israel decisively defeated the surrounding Arab armies in a pre-emptive act of self-defense, Israel and the Jewish world rejoiced. When the United Nations Security Council declared a cease-fire after 132 hours of fighting, Israel had added 42,000 square miles to what the Israeli diplomat Abba Eban once called the post-1948 War of Independence’s “Auschwitz borders.” The death toll for Israelis was close to 800, a number far lower than expected, while the Arabs lost some 20 times that number.

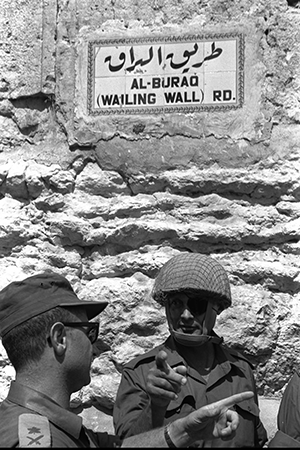

Celebration turned to euphoria, especially when the Israeli commander Mordechai “Motta” Gur announced, “The Temple Mount is in our hands.” During the 1948 war, the Jordanians had captured the eastern section of Jerusalem, dividing the Jewish people’s capital city and later desecrating its synagogues and cemeteries. Israel now controlled the Sinai, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and a reunited Jerusalem.

Three months after the war, the Arab League nations, meeting in Sudan, proclaimed “The Three Nos” in the Khartoum Resolution: “no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel and no negotiations.” United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, which was adopted in November 1967 and focused on the combatants and ignored the Palestinians, encouraged “withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict.” The Israeli cabinet agreed to consider trading some of the land it captured for peace, respecting 242’s wording, which mentioned “territories,” not the territories.

Since those momentous days, much has transpired. East Jerusalem, which Israel annexed in June 1967, became part of Israel’s unified capital city, pursuant to a Basic Law adopted by the Knesset in 1980. Following the Camp David Accords of 1978, Israel agreed to return the Sinai to Egypt. The peace treaty between Egypt and Israel still holds some four decades after being signed in 1979, stabilizing the region. In 1988, Jordan ceded claims to the West Bank to the Palestinians and, in 1994, signed a peace treaty with Israel.

Still, the war created challenges that continue to confound Israel, especially how to achieve peace with the Palestinian people and the wider Arab world while protecting its own fundamental security. After 1967—and especially after the 1970s—the focus of the conflict shifted toward the Palestinians, thanks to Yasser Arafat and the Palestine Liberation Organization’s effective use of terrorism to focus the international community on Palestinian concerns.

Here, we present a timeline of the war and lay out the major issues that emanated directly from those six dramatic days.

DAY ONE: June 5

Israel launches a pre-emptive air attack in the morning and destroys Egyptian Air Force bases. Later it conducts air strikes in Jordan and attacks Syrian Air Force bases. Arabs launch air strikes against Haifa, Netanya and other Israeli locations. Jordan begins artillery fire

in Jerusalem.

DAY TWO: June 6

Within 24 hours, Egypt’s forces begin retreating—although Israel does not secure the Sinai until June 8. Syrians begin artillery fire. Israel takes Ramallah and areas in Jerusalem, including Ammunition Hill and Talpiot. Jordanian forces leave the West Bank.

DAY THREE: June 7

Jerusalem’s Old City and the towns of Nablus and Jericho fall to Israeli forces. Egypt and Jordan turn down United Nations and Israeli cease-fire initiatives.

DAY FOUR: June 8

Egypt accepts a cease-fire. Israel captures Hebron. Fighting with Syria continues along the Golan.

DAY FIVE: June 9

Israeli elite forces, including the Golani Brigade, attack the Syrian Army on the Golan Heights.

DAY SIX: June 10

Israel takes Kuneitra on the Golan. A cease-fire is declared on all fronts and signed the next day.

TWO-STATE SOLUTION

In 1993, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat exchanged letters of mutual recognition that set the stage for the signing of the first Oslo Accord in a ceremony on the White House lawn. That agreement, followed by others in 1994 and 1995, set forth a negotiating framework and identified permanent-status issues that needed to be resolved through direct negotiations, including security, borders, Jerusalem, refugees, settlements and relations with Israel’s other Arab neighbors. The accords did not specify the form of any eventual Palestinian entity.

In addition, these agreements led to the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a provisional government in the West Bank and Gaza. The West Bank—also referred to as Judea and Samaria—was divided into three areas:

• Area A, where the PA has full security and civil control, includes some of the largest Palestinian cities, like Ramallah, Nablus, Bethlehem, Jericho, Jenin and most of Hebron;

• Area B, where Israel is responsible for security and the Palestinians for civil affairs; and

• Area C, where Israel maintains full control over areas in which the majority of Jews live, including Ma’ale Adumim, Gush Etzion, Givat Ze’ev and Modi’in Illit.

An international consensus—grounded in the United Nations charter recognizing people’s right to self-determination—has emerged that the Palestinians should achieve an independent state, living with Israel in peace. This is known as the two-state solution. Despite investing significant time and energy in the peace process, the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama all failed to help the two sides reach a comprehensive, conflict-ending agreement. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak made generous offers to Arafat in negotiations that took place toward the end of the Clinton administration in 2000. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert made even more far-reaching offers to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas during the Bush administration. These offers, which were rejected by the Palestinian leaders, included Israeli withdrawal from most of the West Bank and the Arab neighborhoods in Jerusalem as well as the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

An international consensus—grounded in the United Nations charter recognizing people’s right to self-determination—has emerged that the Palestinians should achieve an independent state, living with Israel in peace. This is known as the two-state solution. Despite investing significant time and energy in the peace process, the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama all failed to help the two sides reach a comprehensive, conflict-ending agreement. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak made generous offers to Arafat in negotiations that took place toward the end of the Clinton administration in 2000. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert made even more far-reaching offers to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas during the Bush administration. These offers, which were rejected by the Palestinian leaders, included Israeli withdrawal from most of the West Bank and the Arab neighborhoods in Jerusalem as well as the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

Israel’s current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has recognized the right of the Palestinian people to a state and insists they reciprocate by recognizing Israel as the Jewish state—not as a precondition to negotiations but as an outcome of them.

Since the idea of a two-state solution began to be pursued seriously in the 1990s, it was assumed that a future Palestinian state would include both the West Bank and Gaza. Egypt did not want the heavily populated Gaza Strip, which Israel controlled until Prime Minister Ariel Sharon enacted a unilateral disengagement in 2005, uprooting its settlers and enabling the PA to fill the vacuum. Hamas, a terrorist organization committed to Israel’s destruction and often hostile to Egypt, then wrested control of the Gaza Strip from the PA. This has created another serious obstacle to reaching the two-state solution.

Some Israelis and Palestinians endorse a one-state option. The Jewish one-staters in Israel come mostly from the political right. Motivated by ideology and security worries, they do not want to relinquish any part of the biblical Judea and Samaria. On the other side, there are Palestinians who seek one binational state either because they reject Israel’s right to exist or out of despair from two decades of failed peace negotiations.

SETTLEMENTS

In the 1967 war, Jordan lost both East Jerusalem and the West Bank, territory it had captured in the 1948 war but had never been recognized as belonging to Jordan by the United Nations. Negotiators in 1949 drew the armistice line in green, which is why Israel’s pre-1967 border is called the Green Line. Some 400,000 Israeli Jews have moved to the West Bank since 1967 and live among as many as 2.5 million Palestinians, making this a major flashpoint.

The first settlements reinforced a security buffer against Jordan. Gradually, cheaper housing lured some Israelis to the area, while others were drawn ideologically to the heartland of the ancient Israelite kingdom. Eighty percent of the settlers live in major population blocs adjacent to the pre-1967 boundaries. Israelis across the political spectrum do not support relinquishing these blocs, which now contain well-established cities, in any future peace agreement.

The international community believes these settlements violate international law and the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits an occupying power from importing civilians. Many Israelis insist the convention is irrelevant in this case. They note there never was a recognized sovereign state in the West Bank, they have legal and historic ties to the land and the Israelis moved into the area freely.

United States policy has generally opposed settlement activity, sometimes distinguishing between natural growth within settlements located near the pre-1967 border and those in the heart of the West Bank that would make separation into two states more challenging. Before Israel disengaged from Gaza in 2005, Bush sent Sharon a letter recognizing “new realities on the ground,” stipulating it would be “realistic to expect that any final-status agreement will only be achieved on the basis of mutually agreed changes that reflect these realities.” Sharon interpreted this letter as an American guarantee that in a final agreement, Israel would keep the heavily populated settler blocs in exchange for some territory inside Israel’s pre-1967 borders.

JERUSALEM

Despite israel’s declaration of united Jerusalem as its capital, foreign embassies are in Tel Aviv because the international community has not recognized Israel’s sovereignty in the city. Palestinian policy considers Jerusalem its capital, too, emphasizing its Muslim holy places, along with more than 300,000 Palestinian Arabs living there, approximately a third of Jerusalem’s population.

REFUGEES

In the 1967 war, between 175,000 and 250,000 Palestinians became refugees, some for a second time since 1948. Palestinians assert a “right of return” under United Nations resolutions that would enable those refugees as well as the refugees from Israel’s War of Independence—and their descendants—to return to their homes inside Israel. While this is another permanent-status issue, most Israelis reject an unfettered Palestinian refugee return. Backed by United States policy, Israel believes Palestinian refugees and their descendants could be resettled in a future state of Palestine or elsewhere, while compensation for lost property could be considered. Many also want compensation for the approximately 850,000 Jewish refugees who fled to the Jewish state after 1948, escaping violence in their native Arab countries.

SECURITY

Not surprisingly, security remains Israel’s priority. Despite its powerful army and repeated military victories since June 1967, Israelis legitimately feel embattled and vulnerable. The threat of concerted aggression by Arab states has receded. But Iran regularly threatens to wipe out Israel while seeking to build nuclear weapons. Moreover, Israel has suffered from waves of Palestinian violence, incitement and celebration of terrorists as “martyrs.” Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza, followed by the Hamas coup there, led to underground tunnels and barrages of rockets aimed at cities in southern Israel like Sderot. Accusations that Zionism is racism and campaigns to delegitimize Israel also reinforce a continuing sense that many Palestinians are still fighting the 1948 war over Israel’s existence, rather than the 1967 war over Israel’s future borders. Israel’s insistence on demilitarizing a future Palestinian state, maintaining Israel Defense Forces deployment in the Jordan Valley and recognition of Israel as the Jewish state all must be understood in this context.

At the same time, Palestinians see themselves as a victimized, stateless people suffering under the occupation of a powerful, militarized country. They resent the rhetoric of Israeli maximalists who continue to lay claim to the entire West Bank, the ongoing growth of settlements and the behavior of settler extremists.

RELATIONS WITH SYRIA AND THE WIDER ARAB WORLD

For years, syria had bombarded northern farms and villages from the strategic Golan Heights. Israel’s two-day conquest of the territory in 1967 ended the threat—although Syria almost reconquered the territory when it and Egypt surprised Israel with an attack in October 1973, setting off the Yom Kippur War. In 1981, Israel annexed the Golan Heights—although it considered exchanging the land for a peace treaty with Syria in the 1990s. Syria’s civil war today makes most Israelis relieved that they retained the territory, which now buffers Israel from the chaos.

As the Middle East changes, possibilities for peace wax and wane. Currently, fears of an aggressive and hegemonic Shi’ite Iran in the region have led Sunni Arab states, spearheaded by Saudi Arabia and Egypt, to see Israel as a strategic ally. That shift has led some to hope for an “outside-in” approach to peacemaking to resurrect the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002, which offered normalized relations with Arab countries in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from all 1967 territories and a “just settlement” of the Palestinian refugee issue.

Fifty years later, the issues persist, and people still seek some comprehensive solution. But just as few in 1967 would have predicted how strong, stable and prosperous Israel would be today, we, too, can hope that Israeli and Arab leaders will defy the past and find the courage to achieve peace.

Martin J. Raffel, former senior vice president at the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, writes a biweekly column for the New Jersey Jewish News and consults for nonprofit organizations. Gil Troy is a professor of history at McGill University in Montreal and the author of 11 books; his next book will be an update of Arthur Hertzberg’s The Zionist Idea.

For more of our coverage of the Six-Day War 50 years later, please read:

The War that Changed Everything—for Israel, for Me

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] This comprehensive article looks back on how the Six Day War transformed Israel – for better or for worse. Recalling how Israeli society moved from terror to euphoria in just a few weeks, the authors provide a brief timeline of the major events of the war and a summary of the major outcomes with which the country is still struggling today, such as the Peace Process, Israeli settlements, the status of Jerusalem, Palestinian refugees, Israel's security concerns, and Israel's relationships with other Arab nations. Published in Hadassah Magazine, this article was written by Martin J Raffel, former senior vice president at the Jewish Council for Public Affairs and Gil Troy, professor of history at McGill University. […]