Wider World

Feature

A Medieval Haggadah’s Long Journey Home

From Lleida, the road to the Monastery of Poblet passes fields full of olive, apple and almond trees. Closer to the religious outpost, a reddish hue becomes more dominant as the trees give way to rows and rows of grapevines. The monastery, located in the province of Tarragona in Catalonia, Spain, stands in the middle of all those vines. Its buildings are an eclectic mix of architecture from the 12th to 16th century. The courtyard in front carries whiffs of fermenting grapes newly harvested, while its back courtyard teems with visiting schoolchildren competing in a sack race.

One of the largest Cistercian abbeys in the world, Reial Monestir de Santa Maria de Poblet is considered a symbol of Catalonia: Eight Catalan kings are buried there. But I’m not visiting to learn about the role the Unesco World Heritage site played in the general history of the region or about its artistic riches, which include historical religious works like the revered alabaster altarpiece created by Damia Forment in 1529. Instead, I am here to understand how this bastion of Christian thought came to house a major relic of Jewish history.

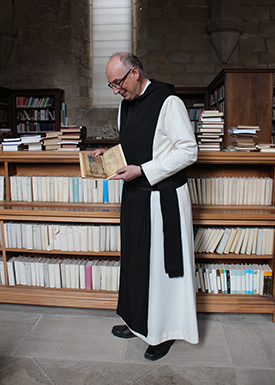

After walking across the two courtyards, I approach the defensive wall, which surrounds the complex’s three enclosures. I enter the monastery through the Royal Doorway—the main gate of the defensive wall—flanked by two polygonal towers. Fra Xavier Guanter, the monk in charge of the monastery’s library, meets me in the visitor’s hall. A tall man in his 50s wearing the traditional Cistercian habit of white tunic and black scapular, he carries a small manuscript in his hands.

“Here,” he says. “This is the Haggadah you came to see.”

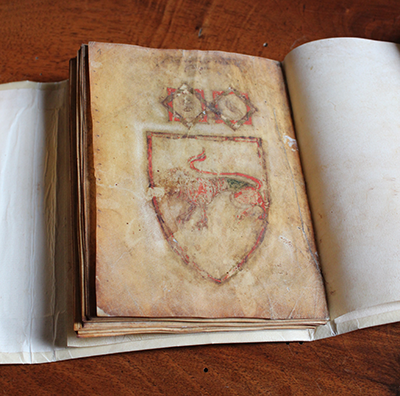

The Haggadah de Poblet—named for the monastery that has given it refuge—is one of 10 known illuminated Haggadahs made for the Jewish community of Catalonia during the 13th and 14th centuries. A tiny book of 38 vellum leaves, it measures only about six-and-a-half inches by five inches. It is bound in flyleaf—blank leaves of paper at the front and back of a book—from what’s believed to be the beginning of the 19th century. When I open it, I see the first illustration: a fiery lion enclosed within the bounds of a shield. The picture has largely rubbed off, and although most of the lion is missing, the red pigment used in its tail, in the shield’s border and in the outlines of two octagonal stars located on top of the shield survive.

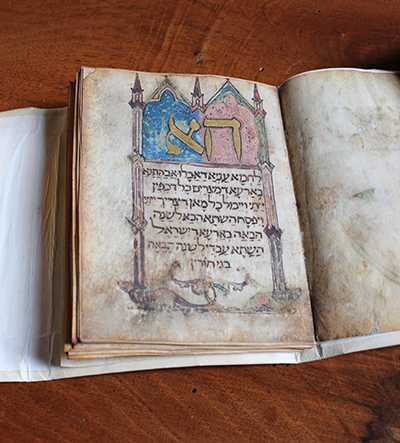

Compared with its more famous brethren—the Sarajevo and the Golden Haggadahs—the Poblet manuscript is modest. It has just five illustrations, only one featuring gold leaf. On the second page, a tall, gothic-like architectural structure frames the opening text. Skimming through, I find a drawing of another lion, a matzah decorated with a Star of David and a representation of maror. Yet, despite its simplicity, there is something special about this tiny book. Created in Catalonia and taken out of the country when its owners fled either the pogroms of 1391 or the expulsion of 1492, it is the only known illuminated Haggadah that returned home to the Iberian Peninsula.

“I was here when it arrived,” says Guanter, “a couple of years before the publication of its facsimile.” He is referring to the edition put out by the monastery and the publishing house Editorial Riopedras in 1992 to mark both the resurfacing of the Haggadah and the 500-year anniversary of the official expulsion of Jews from Spain. “When we opened a sack of donated books, we saw several volumes that belonged to the monastery prior to its closing in 1835, a gigantic edition of Don Quixote and this tiny book with Hebrew writing. Fra Agustin Altisent, the previous librarian, immediately brought it to the University of Barcelona.” (The monastery was confiscated by the government in 1835 and didn’t reopen until 1940, after a 10-year restoration project.)

Altisent contacted José Ramón Magdalena Nom de Déu, currently a professor of Hebrew studies at the University of Barcelona. Until the Poblet monk showed up in his office that day, Nom de Déu didn’t know of any illuminated Haggadahs that had returned to the Iberian Peninsula. Careful study and analysis of its paleography, scribal manners and iconography placed the making of the manuscript somewhere in the second half of the 14th century. The first owner, according to Nom de Déu, must have been a “pious, learned and eminent member of the community, besides being sufficiently wealthy to be able to afford an expensive Haggadah.” The owner would have come from the village of Peralada, near Girona, Nom de Déu believes. Although there was no organized aljama, or Jewish community, in Peralada, that area of Catalonia outside of Barcelona was well known for its Jewish heritage.

The earliest reference to Jews living in Catalonia, specifically in Barcelona, appears in documents dating back to 875 to 877 CE. Working mainly as traders and moneylenders, but also as scientists, physicians, theologians and poets, the Jews of the Kingdom of Aragon and Catalonia were the property of the king—in his service and under his protection.

“They often served as administrators, secretaries and even ambassadors,” says Maria Josep Estanyol i Fuentes, professor of Semitic philology and a specialist in medieval Jewish history at the University of Barcelona. “Because they spoke many languages and had the kind of education that Christians didn’t have, the kings [throughout the Iberian Peninsula] appreciated them.” The same couldn’t be said about the common people, however.

While some Christians worked side by side with their Jewish neighbors, many others despised them. “El pueblo bajo, the common people, often had a very bad impression of the Jews,” says Estanyol i Fuentes, “most of it because of the church. When anti-Jewish uprisings happened in 1348, with Jews being blamed for the plague, and in 1391, following a series of similar riots throughout the Iberian Peninsula, the Jews had more problems with the common people.”

The attacks and the forced conversions of 1391 only led to more animosity toward the Jews, culminating with the now infamous decree of 1492 when Catholic monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand ordered forced conversion or the expulsion of the Jews. While close to 50,000 people converted, around 40,000 fled. It’s not possible to say with certainty when the Haggadah de Poblet left Catalonia—whether following the unrest of 1391 or the expulsion of 1492—or when it returned. But research has determined that it resided in at least two other countries before it came back.

Going through the manuscript, Nom de Déu discovered annotations indicating that the Haggadah first went into “exile in Provence or the papal state of Avignon [in southern France], and later Italy,” he relates. One annotation, dated 1555, was most likely made by a church censor in Rome after examining the manuscript. And as late as 1680, an annotation implies the Haggadah was still in Italy.

No one knows how the Haggadah returned, but Nom de Déu thinks that perhaps it came back with José Maria de Barberà i Canturri. A priest and professor of humanities at a Tarragona seminary, Barberà i Canturri was also an avid Hebrew scholar and translated several works from Hebrew into Spanish. Since the Haggadah arrived in Poblet as part of a donation of books that included those from his personal collection, it is possible that he was the one to acquire the manuscript in Italy and bring it back to Spain.

Donation aside, I was still curious how a Christian institution—one that has long been part of the same church that was responsible for creating the Inquisition and for the persecution of the Jews—ended up being the place of the Haggadah’s final residence. All the other illuminated Catalan Haggadahs are held in museums or government-managed collections. How peculiar is it that the Catholic Church is now in charge of safeguarding this Jewish manuscript?

When I pose that question to Estanyol i Fuentes, she laughs. We are speaking over the phone but I can still hear the uneasiness behind her response. “It sounds incongruent,” she says, “but I don’t think it is. There have been cases in which things like books and works of art that otherwise would have been lost were conserved thanks to the church. In this case, we should be thankful that the Haggadah is still with us because of the Poblet monastery.

This Haggadah is our patrimonio nacional [national heritage] not only because of its Jewish history but also because of its artistic value.

“Besides,” she adds, “it’s important to remember that many of these Haggadahs were made with the help of Christians. The illustrators who illuminated them often came from Christian workshops that worked on Christian books, too.”

There is also a connection between the monastery itself and its neighboring Jewish community that goes back centuries. When I visited, Guanter showed me several documents—written in both Hebrew and Latin—delineating funds loaned to the monastery by local Jewish lenders. But more curious was a notation made in the minutes of the general meetings of the Order of Cistercian Monks, collected since 1116. The first-ever mention of the Poblet monastery appears in 1198, and it’s connected to the area’s Jews. Apparently—and much to the chagrin of his superiors—one of the monks employed a local Jewish citizen to learn Hebrew.

When I ask Guanter if the Haggadah receives many visitors, he mentions only one: an older Jew from Argentina who now lives in Israel and who believes the Poblet Haggadah once belonged to his family. “If there are school visits,” Guanter says, “they come for the history of the monastery and the art it contains. They don’t ask about the Haggadah.”

Estanyol i Fuentes thinks she knows why there is no interest. “There is very little knowledge of Jewish culture in Spain,” she says. “We’ve been living for centuries without knowing it—and sometimes even rejecting it.”

Some hope this could soon change.

In addition to teaching at the University of Barcelona, Estanyol i Fuentes is now the president of Xarxa de Calls De Catalunya, the Network of Medieval Catalan Jewish Ghettos. In existence since 2013, the organization collects artifacts and documents that shed light on the history of Jews in Catalonia. Although relatively new, the initiative has already attracted the attention of many municipalities eager to reclaim their Jewish heritage.

When I leave the monastery, the schoolchildren are getting ready to depart. Perhaps the next time they come to Poblet, their visit won’t solely include the role the monastery had in the history of Catalonia—but also the one it now plays in preserving the history of Catalonian Jewry.

Margarita Gokun Silver is a writer and artist living in Madrid. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Forward, The Washington Post and NPR, among others. You can see more of her writing at margaritagokunsilver.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Shirley Newberger says

Where can one purchase a copy?

Susana Windt says

This is very interesting, thank you. Never heard of the Poblet Haggadah. In a way it is a good thing people “do not know”, it would not be so accesible if they “knew”. One wonders how many jewish treasures are hidden in unimaginable places.

Has any one recorded the story of the old man that visits the Haggadah? There is probably no historical proof, however tales are a common source of historical facts.

Magda Saura i Carulla says

Dear Susana,

Historic French Catalonia and Spanish The The Cistercian Abbey of Poblet is an important World Heritage UNESCO site. Catalonia used to have large Jewish communities till the end of the XV th.century. Should not surprise you at all to find “hidden”this manuscript in “unimaginable places.” Try to study your own Jewish background as much it is also part of my own medieval, Catalan cultural heritage.

Magda Saura i Carulla says

Dear Susana,

Historic French Catalonia and Spanish Catalonia. The Cistercian Abbey of Poblet is an important World Heritage UNESCO site. Catalonia used to have large Jewish communities till the end of the XV th.century. Should not surprise you at all to find “hidden”this manuscript in “unimaginable places.” Try to study your own Jewish background as much it is also part of my own medieval, Catalan cultural heritage.