American View

Feature

Confronting Anti-Semitism in a Small Montana Town

When Rabbi Francine Green Roston decided to leave her Conservative pulpit in South Orange, N.J., and move with her husband and children to the remote town of Whitefish in northwestern Montana, she knew they were in for big changes.

They’d be trading a work-centered East Coast life for a rural Western town of 6,000 where the biggest attraction is nearby Glacier National Park. Her kids would be moving from a Jewish day school to schools where practically everyone is white and Christian. And buying kosher meat would no longer be as simple as going to the supermarket.

But what Roston, 48, could not anticipate when they made the move in 2014 was that she would find herself at the center of a confrontation between Jews and supporters of a local neo-Nazi that would make news all over the country and stoke anxiety about the rise of the so-called alt-right movement. “We never expected to be the target of a hate campaign,” Roston wrote in a widely circulated letter sent in the beginning of the year to rabbis around the country. “This is a time of great anxiety for our Glacier Jewish Community and the city of Whitefish.”

Whitefish is the hometown of alt-right leader and white nationalist Richard B. Spencer. A vocal supporter of President Donald Trump, Spencer made headlines a week after the election by delivering a speech at a neo-Nazi conference in Washington, D.C., that ended with Spencer roaring, “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!” to a smattering of Nazi salutes.

In the ensuing weeks, the small Jewish community—the rabbi counts about 100 known Jewish households in the region, known as the Flathead Valley—was subject to a concerted campaign of online harassment

and threats.

In mid-December, The Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website, called on followers to “take action” against Jews in Whitefish, ostensibly because the negative attention surrounding Spencer’s group, the National Policy Institute, was making it difficult for his mother to sell the family property in Whitefish that was listed in public records as the group’s primary office. The Daily Stormer listed the names, email addresses, phone numbers and physical addresses of several Jewish residents of Whitefish, prompting local police to step up security measures.

Meanwhile, local activists, led mostly by non-Jews, mounted their own counter-campaign. They held community meetings, distributed “Love Lives Here” signs and held a “Love Not Hate” rally in downtown Whitefish on January 7 that brought out hundreds of supporters in sub-zero temperatures. Earlier, they had asked state residents and businesses to place menorahs or a picture of a menorah in their windows during Hanukkah as a sign of solidarity. That effort echoed a famous act of solidarity in Billings, Mont., in 1993, in which hundreds of non-Jews placed menorahs in their windows after an unknown assailant threw a brick through the bedroom window of a Jewish home displaying a menorah.

In mid-January, the police chief in Whitefish nailed a mezuzah to the doorpost of the police station as a symbol of solidarity with his city’s beleaguered Jews. Around the same time, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock met privately with the Jewish families being harassed, and he and the state’s two senators, congressman and attorney general issued a joint statement of support and unity against anti-Semitism.

“In our darkest nights this winter, this state, our elected representatives, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, you all lifted us up,” Roston said in a speech at the January rally, wearing a colorful talit over her long winter coat. “You let us know we are not alone.”

The neo-Nazis, meanwhile, were in the midst of organizing their own rally. But just days before the planned demonstration, Whitefish city officials denied a permit to the group, saying it had failed to file the necessary paperwork. Organizers announced they would reschedule the march.

Through it all, Roston tried to keep a low profile while rallying locals against the hate campaign and serving as one of the most visible representatives of the local Jewish community. She is, after all, the only active rabbi in town (there’s also a local retired rabbi).

Roston didn’t plan to become the town’s rabbi when she left her New Jersey congregation of more than 500 members just a few years ago. She was burnt out from the rabbinate and looking to lead a quieter lifestyle where she could regularly have dinner with her family and spend more time outdoors, she said. She and her husband, Marc, had fallen in love with Whitefish on successive summer trips and decided it was time to live their dream.

“As a congregational rabbi, there’s so much you’re giving out to people, and you have to make sure you have enough spiritual energy coming in. I was really drained,” Roston said in a 2015 interview with JTA. “In nature, I really refuel. I feel more connected with God’s power and presence in the world.” In Whitefish, she could take daily walks in the woods and on Shabbat, instead of going to synagogue, she might go hiking or kayaking.

Very quickly, though, Roston started to plant Jewish roots in her new community. She began organizing occasional get-togethers, including Shabbat and Yom Kippur services and a Purim party. Soon, the rabbi was establishing a formal community association for Jews in the area.

Today, the Glacier Jewish Community-B’nai Shalom meets about three times a month, and Roston is formally its rabbi. Though she hails from a Conservative background—she was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City and was the movement’s first female rabbi to serve in a congregation of more than 500 members—B’nai Shalom is nondenominational and open to all.

The harassment following Trump’s election wasn’t the first time Roston had experienced anti-Semitism in Whitefish. During their second year in town, Roston’s son, now in eighth grade, watched his classmates sing “Happy Birthday” to Hitler on April 20. In her daughter’s 10th-grade AP history class, a classmate declared that the Holocaust wasn’t that bad.

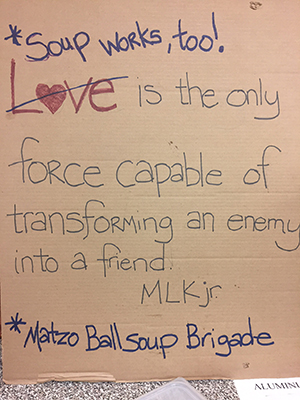

But nothing resembled the intimidation that followed Trump’s election. After neo-Nazis announced plans for their march, Roston said the Jewish community would not hold a counter-demonstration, which the experts warned would only encourage the attention-seeking extremists. Instead, they made plans for a community gathering with comforting Jewish staples like matzah ball soup.

Once again, the idea for the program came from non-Jewish supporters, including a local farmer and activist named Pam Gerwe.

“I was feeling pretty frustrated by the whole thing that was going on with Richard Spencer, and I just hated that people were getting targeted. I wanted to do something,” Gerwe said. “I’m a farmer, and I see food as a real unifier. I thought the soup event would be an easy way for people to do something that was cooperative and healing and bringing people together. And matzah ball is really the only Jewish soup I know about.”

Held in the Whitefish Middle School cafeteria on Martin Luther King Jr. Day—the same day the neo-Nazis had planned their march—the program drew about 300 people. Local businesses and residents donated the supplies, and a couple of days before the event, Roston took charge of teaching about 20 volunteers at a local food bank how to make the matzah balls.

Months later, Roston is still marveling at the outpouring of support. During the height of the ferment, she said, she received hundreds of handwritten cards and letters of support, many from

children around the country. After feeling threatened and targeted and attacked, “I’d be lying if I said we didn’t think about the question of whether we had moved to the right place,” Roston said. “The message from Montana citizens from those cards was: We do belong and this is our home. It was just this immediate, loving response. They couldn’t stop the attack, but they helped us feel like we were not alone.”

So did the larger Jewish community. The Anti-Defamation League reached out to lend support and Secure Community Network, the national Jewish security program, dispatched a professional from Seattle to help the Jews with security assessments. “It felt lifesaving at the time,” Roston said, fighting back tears. “You go to live in a far-off place and cannot be immediately connected with Jewish institutions. That’s a part of life here, and that’s OK. But that they showed up to take care of us because we’re a Jewish community—it was extraordinary.”

Since the neo-Nazi flare-up, some local Jews who hadn’t been involved with the Jewish community have connected, and Roston has discovered a handful of people in town whom she hadn’t known were Jewish. “People don’t really move here with Jewish community as a priority, but the people here still have a sense of Jewish identity,” she said.

Though the firestorm has since died down, activists plan to stay on guard. Another “Love Not Hate” rally is being planned for the summer. Roston is talking to the school system about educational initiatives to help children fight hate and bigotry. A group of local faith leaders, including Roston, held their first-ever interfaith clergy meeting. And the rabbi is keeping her eye out for any further harassment.

“As a community leader, I’m going to continue to watch white supremacists and white nationalists in my state and monitor hate chatter,” she said. “I’m going to continue to watch Richard Spencer and point out the anti-Semitism, racism, sexism and bigotry at the core of his political philosophy.”

Uriel Heilman is a journalist who works for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in New York.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply