American View

Life + Style

He Was Larger Than Life Despite Disability

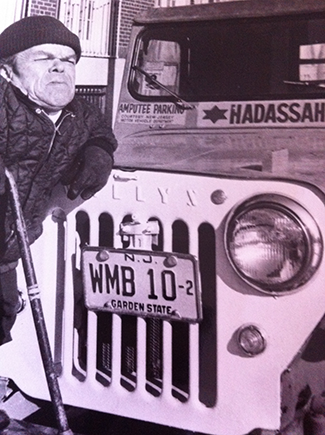

If you lived in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania between 1940 and 1980, you likely would have seen my great-uncle, Moishe Morris “Mace” Bugen, driving his open-roofed Jeep painted with blue and white stars and a sign that read “Hadassah” across the front window. Many thought of Mace as a one-man parade of Jewish pride: Pedestrians would call out “Hey Macey” when they saw him coming, and he would wave back with an official air.

Hadassah, his beloved Jeep, was equipped with custom pedals that reached his feet. Mace, my grandmother’s younger brother, was born in 1915 with achondroplasia, a bone-growth disorder that causes the most common form of dwarfism. His head grew normally while his height topped out at 43 inches. Mace had a hump on his back and a crooked spine that deteriorated as he aged. However, what made Mace memorable were not his physical characteristics but his resilience in the face of society’s prejudices and his oversized chutzpah.

In examining Mace’s life for my recent book about him, The Little Gate-Crasher: The Life and Photos of Mace Bugen, I was reminded how far the United States has come in advancing the rights of people with disabilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, which, among its provisions, requires that public spaces are accessible for people with mobility issues. When Mace drove to events, he often had to park on the lawn close to an entrance because there were no designated handicapped spaces.

As the mother of a child with cognitive disabilities—my 14-year-old son, George, is on the autism spectrum—I am keenly aware that families still need to fight for their children’s access to education, therapy and inclusion in the community. I have newfound appreciation for how my great-grandparents made sure that even if the world outside scorned Mace, home was a place of unconditional love. This was quite unusual for that era, when children with differences were typically sent

to institutions.

Mace had a bar mitzvah, became his school’s basketball team manager and graduated from high school. He also had a taste for adventure. When he was a teenager, his older brother Phil helped him get a bus ticket to Chicago to see the boxer Joe Louis in action. Walking through a sea of people, Mace made it to the ringside, jumped in and wished Louis “Jewish luck.” After Louis won that match, Mace was seen kissing boxing gloves on an RKO newsreel that was shown all over the world.

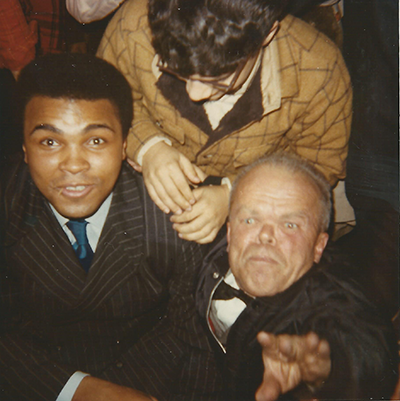

Mace went on to become a successful real estate agent, and he was dedicated to his aging parents. He was often seen driving around the area picking up used clothing that his mother would box up for refugees in the new State of Israel. He and his family were strong Zionists and fervent supporters of Hadassah Hospital, as evidenced by the name of his Jeep. He continued to pursue his hobby of meeting and taking photos with celebrities—his impressive collection includes Joe DiMaggio, Ella Fitzgerald, Muhammad Ali and Sammy Davis Jr.

Despite Mace’s successes, his choices were limited because of the lack of accommodations for his disability. For example, he gave up his dream of going to law school since there was no way for him to carry around the heavy books. There was no awareness then, as there is now, that reasonable accommodations should be made.

For my part, I remember him as the most fun-loving adult from my youth. When he came to visit, his pockets were full of candy and he piled my siblings and me into Hadassah to go get ice cream. When he died in 1982, his celebrity photo albums went to my grandmother and, after she died, to my mom. My mom encouraged me to take the photos and weave together a narrative about how Mace rejected society’s prejudices to become one of the happiest, most successful people she ever knew.

As my research on Mace deepened, I discovered a kindred spirit in my Great-Grandmother Sarah. Like her, I have a child with differences. But I live in a time when I have support in my community and can easily go online to find both resources and other parents who share my experience. My great-grandmother had none of that; she used her instincts and her heart to guide her parenting of Mace.

In sharing Mace’s story, I am claiming my family’s legacy of honoring differences and holding up expectations that my son’s life will not be defined by his disability. While the parallels between my great-uncle’s dwarfism and my son’s autism may not seem obvious, both their lives reflect the tremendous diversity of the human experience—and that is to be celebrated. My son struggles with communication and social understanding, struggles he will likely have all his life. But with the help of his family and his community, he can access love and affection.

My hope is that as our Jewish community continues to raise awareness about the need for welcoming, supporting and creating accommodations for people with disabilities, we remember and model the stories of people like Mace who claimed his right to be a valued member of his community.

Gabrielle Kaplan-Mayer, a writer and educator, leads disability awareness training in Philadelphia’s Jewish community as director of Whole Community Inclusion at Jewish Learning Venture.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Meredith says

Thank you for sharing; we benefit from being reminded that what we enjoy today, is not a given, but had to be fought for and we need to continue our endeavours to treat all people fairly.

Rodger Castleberry says

What a marvellous, inspiring story of a “Giant” of a man who overcame his disability to live on in cherished memory by those who knew, met or were touched by him in whatever manner.

God Rest You, Mace! Pray to meet you in the great beyond, having only seen you once in your fabulous “Hadassah” Jeep.

Shalom.