Hadassah

Feature

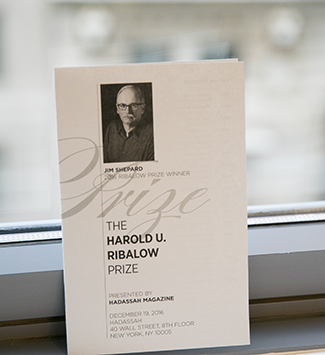

Ribalow Prize Winner Is ‘Ultimate Monument to Jewish Loss’

Reena Ribalow, daughter of Hadassah Magazine‘s literary prize namesake, Harold U. Ribalow, called Jim Shepard’s prize-winning Book of Aron “a searing, hallucinatory testament of a novel, composed of detail upon unbearable detail—a devastating historical mosaic of incomprehensible cruelty and barbarism.” A resident of Jerusalem, Reena was unable to attend the Dec. 19 awards ceremony, but her words were read by her cousin, Leah Nadich Meir, niece of Harold Ribalow.

And don’t miss reading Jim Shepard’s award ceremony remarks or the talk delivered by guest speaker Matthew Thomas.

This prize has known many losses in the past few years. My brother Meir, of course, with whom I conceived the prize and saw it come to life at Hadassah Magazine: who read with me the piles of books—he on one continent and I on another—and in long, laugh-punctuated phone calls, chose the nominees from among them: who spoke to you every year with humor, grace and profound love about my father and what he was: Meir, who left too soon his rich creative life and is remembered by all those he encountered: who is mourned by countless friends—many of them sitting in this audience, honoring him and the prize to which he dedicated himself, friends who continue years later to remember and miss him in ways only a few fortunate people are remembered or missed. My mother, who took the pride of a tigress in this prize and in the memory of my father and their life together, and who for years offered her always definitive, often idiosyncratic and thoroughly irreversible opinions about which book deserved the prize, is also gone. So is my father’s sister, Martha Hadassah Nadich, who, with her background in Hebrew and Jewish literature, and her position as the erudite Rebbetzin of the Park Avenue Synagogue—coupled with her fierce love for and pride in her brother—was one of the nominating committee until she was unable to go on. Then last year Alan Tigay, editor of Hadassah Magazine from the prize’s inception, who tended and nurtured it for over 30 years, retired, leaving us all scrambling to gather together the details he had so effortlessly assembled without anyone realizing how much he did. In the same year, we lost our permanent judge, the magnificent Elie Wiesel, who lent his vast knowledge, deep instincts and noble spirit to the endeavor almost from its start.

Sometimes I feel like a figure in Greek myth, alone and embattled, defending the life of this prize. But since our prize is a Jewish one, the losses have also shown that we are a community, and that the task is bigger than any one of us. Alan and Sharon Pomerantz—a woman who, in addition to being a fine writer, is a cherished friend of Meir’s, of mine, and of Hadassah Magazine—stepped in as judges. My daughter, Riora Kerr, became my partner in reading the books. Lisa Hostein, Hadassah Magazine’s new editor, took up the reins, while managing editor Zelda Shluker continued her expert and invisible mending, and Deb Meisels dedicated her energies to keeping things going, despite her own health issues. Hillary Clinton (the right person to quote in a year of loss) said it takes a village, and this year it really did. But what is most important is that we had a village, and a goal greater than any one of us—something worth fighting for and preserving: the pursuit of excellence in the honoring of an Anglo- Jewish Literature, which we have achieved with the Harold U. Ribalow Prize, against the slings and arrows of sometimes beneficent, often outrageous fortune.

It is somehow fitting that the winning book in such a year is about the ultimate monument to Jewish loss, the Holocaust. The Book of Aron is a searing, hallucinatory testament of a novel, composed of detail upon unbearable detail—a devastating historical mosaic of incomprehensible cruelty and barbarism. Piece by harrowing piece Jim Shepard creates the reality of life in the ghetto, through the child Aron, and his savior, the heroic Janusz Korczak, who protected the children of his orphanage as long as he could, ultimately choosing to go with them to their death in Treblinka. This novel, astonishingly researched and remarkably imagined, concerns itself with the elemental struggle, not just to survive, but to maintain against all odds the divine spark of what make us human. As one reviewer said : “(Jim) Shepard, a National Book Award finalist who’s been called America’s finest living writer, has created a stark masterpiece. His brilliant, iconic book about genocide and the resilience of the human spirit ranks with the best literature that explores the dark side of the human soul.”

This is a book, and a subject, that fittingly honors the memory of Elie Wiesel as a child survivor. It, like Wiesel, insists on remembrance, and facing the unhealable wound of the Holocaust. Jewish literature is our record of where we have been, but it is also the revelation who we are, and the prophecy of where we are going. We are a people of the book, because our strength and our vision rise from our texts and our narrative. The word is sacred in Judaism; through its power we have over and over again risen from the ashes as individuals, and as a people. Elie Wiesel himself wrote, “Others have been here before me, and I walk in their footsteps. The books I have read were composed by generations of fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, teachers and disciples. I am the sum total of their experiences, their quests. And so are you.”

The Ribalow Prize is dedicated to this faith in the written word and the continuity of the Jewish story, because the man for whom it was named lived his life in the light of this vision. Many of you have heard about my father over the years, but some have not, and may wonder, who is this man and why name a prize after him? I will tell you why: because before him American-Jewish literature was a nebulous and basically disdained concept. He was one of the first to anthologize and review (in his 15 books and countless articles) novels and short stories by various writers, and recognize and honor them as artists forging a body of distinct English-language Jewish fiction. He often told the story of how American publishing houses would turn down manuscripts by Jewish writers with the caveat, “We have done our Jewish book for the year.” He personally helped and publicized writers such as Cynthia Ozick, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Anzia Yezierska, Edgar Lewis Wallant, Meyer Levin, and too many others to list. He embarked on a solitary mission to republish Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep, which he considered a masterpiece —dragging our entire family up to the Maine poultry farm where Roth was hiding out from his own greatness as a writer. Subsequently Call It Sleep was recognized as one of the seminal American and great Jewish novels. My father did all this selflessly, because he gloried in talent, and believed in the redemptive power of the written word. He always chose writers whose Judaism was positive, over those for whom it was a burden and a neurosis. In the heyday of the Jewish novel, when the heroes of Philip Roth and Saul Bellow came to represent the alienated American anti-hero, through their ambivalent Jewishness, he praised Bernard Malamud, whose Judaism was rich, varied, and bone-deep. This was not a popular position, and he was considered by some both reactionary and old-fashioned. But my father was above all a man of integrity, answering only to his own truth and to his conscience, with no thought of the cost.

The Ribalow Prize is dedicated to this faith in the written word and the continuity of the Jewish story, because the man for whom it was named lived his life in the light of this vision. Many of you have heard about my father over the years, but some have not, and may wonder, who is this man and why name a prize after him? I will tell you why: because before him American-Jewish literature was a nebulous and basically disdained concept. He was one of the first to anthologize and review (in his 15 books and countless articles) novels and short stories by various writers, and recognize and honor them as artists forging a body of distinct English-language Jewish fiction. He often told the story of how American publishing houses would turn down manuscripts by Jewish writers with the caveat, “We have done our Jewish book for the year.” He personally helped and publicized writers such as Cynthia Ozick, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Anzia Yezierska, Edgar Lewis Wallant, Meyer Levin, and too many others to list. He embarked on a solitary mission to republish Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep, which he considered a masterpiece —dragging our entire family up to the Maine poultry farm where Roth was hiding out from his own greatness as a writer. Subsequently Call It Sleep was recognized as one of the seminal American and great Jewish novels. My father did all this selflessly, because he gloried in talent, and believed in the redemptive power of the written word. He always chose writers whose Judaism was positive, over those for whom it was a burden and a neurosis. In the heyday of the Jewish novel, when the heroes of Philip Roth and Saul Bellow came to represent the alienated American anti-hero, through their ambivalent Jewishness, he praised Bernard Malamud, whose Judaism was rich, varied, and bone-deep. This was not a popular position, and he was considered by some both reactionary and old-fashioned. But my father was above all a man of integrity, answering only to his own truth and to his conscience, with no thought of the cost.

Growing up in a house with walls of books—books which were actually read and discussed—we continued the tradition of my grandfather, Menachem Ribalow, the editor of Hadoar, the first Hebrew weekly in the United States. While his father was a leading Hebraist intellectual, my father staked out his claim in the English language; but the pilgrimage was the same—the charting of the Jewish soul and its experience. My brother and I would joke when cartons of books arrived for review, that one day we expected to see a book called The Jew and the Elephant. When I started to get books for this prize, my own kids would read the blurbs and titles and in turn make their jokes (I particularly remember one called Which Big Giver Ate the Chopped Liver.) My daughter tells me that my granddaughter now goes through the boxes of books arriving for her mother to read; at nine-years-old, she picked one up called The Night of the Broken Glass, and said, “That’s a scary name.” (It was—its subject was Kristallnacht.) I took pride in and solace from this story, because I know this is the way Jews were meant to live: to pass on their history through stories, for generations. This is why Shema Yisroel, the essential Jewish prayer, meant to be on our lips as we live and as we die, tells us to teach its precepts “diligently to your children and speak of them when you sit down and when you walk, when you lie down and when you rise”. Passing on the word is the essence of Judaism—not buildings, not governments, not wealth, not treasure. The word. It may be very ambitious to expect our contemporary writers and their novels to be judged by this standard; but, I take seriously the admonition of Pirkei Avot (The Ethics of the Fathers): “It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.” Each book, each writer, each reader, is part of a greater whole—the creation of a culture and tradition of our own making, linked to what came before. As a writer myself I know only too well that we will always fail to be as good as our dreams, no matter how much we strive and how well we write. But, as Samuel Beckett put it: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.”

It may be unfashionable to think of the artist as part of a community, rather than as a brave and intrepid solitary soul. But the older I get, the more I see how we are part of a whole, links in a chain of destiny and history. We cannot always succeed, but we write, read, and award prizes to the books that strive toward the truth to which my father dedicated his life. He was a man of wide and eclectic interests and enthusiasms. He wrote about sports: knew facts about bees and ants, and almost anything else you could imagine: loved D.H. Lawrence : the blues: folk music before hippies ever heard of it: was an expert in the Bloomsbury Group and could never get enough of London. But as his own mother—a highly educated woman with a love for Russian literature, who met many leading Jewish writers and artists due to her husband’s position, and was less than impressed with many of them—used to say (in Yiddish) “The real person is on the page.” The real Harold U. Ribalow was in his books and reviews, writings and essays, and dedication to the finest writers in the Jewish canon. When he was a judge for various Jewish literary prizes, he was deferred to because often he was the only one who had read all the books. He did not read them for the prize, but because they mattered, and because he cared, and because he was a believer. He was not a religious person to put it mildly, but he was a man of deep faith—in the enduring importance and wonder of who and what we are and how we tell it to the world. That is why this prize , which has had the rare privilege of thriving for over 35 years, while most other Jewish literary prizes disappear, is named for him and carried on—year after year—in his memory.

It may be unfashionable to think of the artist as part of a community, rather than as a brave and intrepid solitary soul. But the older I get, the more I see how we are part of a whole, links in a chain of destiny and history. We cannot always succeed, but we write, read, and award prizes to the books that strive toward the truth to which my father dedicated his life. He was a man of wide and eclectic interests and enthusiasms. He wrote about sports: knew facts about bees and ants, and almost anything else you could imagine: loved D.H. Lawrence : the blues: folk music before hippies ever heard of it: was an expert in the Bloomsbury Group and could never get enough of London. But as his own mother—a highly educated woman with a love for Russian literature, who met many leading Jewish writers and artists due to her husband’s position, and was less than impressed with many of them—used to say (in Yiddish) “The real person is on the page.” The real Harold U. Ribalow was in his books and reviews, writings and essays, and dedication to the finest writers in the Jewish canon. When he was a judge for various Jewish literary prizes, he was deferred to because often he was the only one who had read all the books. He did not read them for the prize, but because they mattered, and because he cared, and because he was a believer. He was not a religious person to put it mildly, but he was a man of deep faith—in the enduring importance and wonder of who and what we are and how we tell it to the world. That is why this prize , which has had the rare privilege of thriving for over 35 years, while most other Jewish literary prizes disappear, is named for him and carried on—year after year—in his memory.

How fitting to close with the consummate words of Anne Roiphe, a past winner of the Ribalow prize: “All people have stories. All peoples have legends they tell each other around the tended fire or in the field or forest or in drawing rooms, or in temples or cathedrals. But Jews have made their stories, their history, into the Tallis that wraps itself around the shoulders of all its people, past, present, and future. And this wrapping binds us together, insists that we pass it on to our children, and keeps us from falling apart like so many fragments of an exploding star. We won’t explode until the last Jew alive has forgotten the last Jewish story he heard. “

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply