American View

News + Politics

Unifying for Change: Gender Equity in Medicine

Bonnie Tucker, a middle-aged writer from Houston, has multiple sclerosis, an often debilitating disease of the central nervous system that can cause fatigue, numbness, tingling and pain. Her symptoms began when she was in her 30s, but it took almost a decade for Tucker to receive a diagnosis.

Bonnie Tucker, a middle-aged writer from Houston, has multiple sclerosis, an often debilitating disease of the central nervous system that can cause fatigue, numbness, tingling and pain. Her symptoms began when she was in her 30s, but it took almost a decade for Tucker to receive a diagnosis.

Jewish educator Karen Feit, 66, of Bellport, N.Y., thought her chest pains—far different from those she believed were typical of a heart attack—were caused by anxiety. Yet, recalling information from Hadassah’s heart health program, she went to the hospital and found she had suffered an acute myocardial infarction—a heart attack.

These cases illustrate the continuing failure of physicians to recognize and treat illnesses in women, and the necessity for greater focus on gender medicine—the growing field of research aimed at analyzing the different medical needs of men and women. This vacuum is why Hadassah launched the Coalition for Women’s Health Equity earlier this year, gathering an array of organizations to address the issue.

“Hadassah has convened this coalition because we needed to do something about the pervasive gender disparities throughout the health care system,” says Ellen Hershkin, national president of Hadassah. “We are driven to advocate for women’s health equity with a well-coordinated and unified force that will fight for equality—from prevention and diagnosis to treatment and cure.”

Currently, there are 20 members of the coalition, including the American Association of University Women, American Heart Association, National Organization for Women, National Women’s Law Center, National Partnership for Women & Families, WomenAgainstAlzheimer’s and Black Women’s Health Imperative, among others. Coalition members share information and collaborate on advocacy efforts, and the group is planning a joint legislative agenda for 2017.

In May, a congressional briefing entitled “From Prevention to Cure: Understanding the Impact of Gender Inequity in Health” brought together coalition member organizations and women’s health experts to address risks and make recommendations for legislation surrounding women’s health equity. “Women, mothers in particular, are the cornerstone of family health,” Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.) said at the event. “If we really want to improve healthy outcomes in this great country of ours, then we need to do more to achieve gender equity in health education and health research.”

Experts note that women and men can present different symptoms for the same diseases and react differently to drugs and medical devices. “Women are not just small men,” says Dr. Marek Glezerman, president of the International Society for Gender Medicine and director of the Research Center for Gender Medicine at the Rabin Medical Center in Israel. Dr. Glezerman’s book, Gender Medicine: The Groundbreaking New Science of Gender- and Sex-Based Diagnosis and Treatment, originally in Hebrew, was published in English in July.

“We find ourselves in a situation where we adopt our knowledge from half of the population to the other half,” he says. “That may cause problems in diagnosis and treatment and may be dangerous and even sometimes fatal.”

Dr. Glezerman cites pain treatment as an example of an issue that is too often mishandled. Women are more likely than men to suffer from autoimmune diseases, frequently associated with pain, yet most pain-management drugs have been tested only on men. The result is that women can be either under- or overtreated.

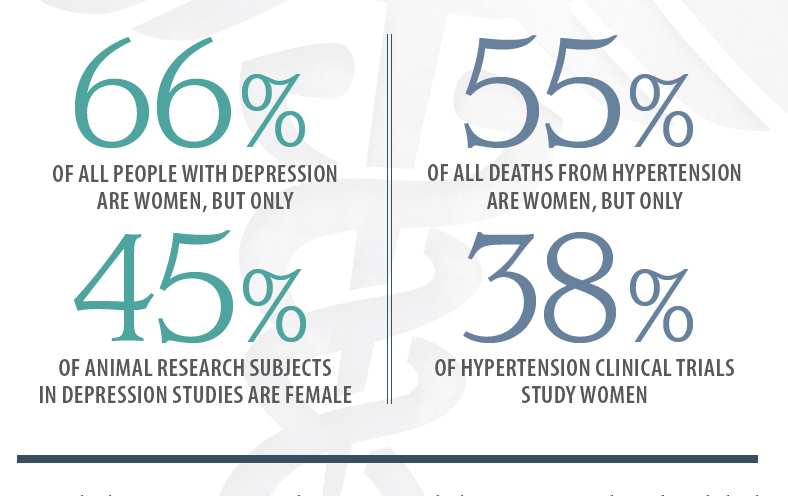

Similar discrepancies pertain to heart disease, which is the No. 1 killer of women in the United States. Yet today only one-third of cardiac research subjects are women.

The most common heart attack symptom is chest pain or discomfort, according to the American Heart Association. But women are more likely than men to exhibit other symptoms. “Women can experience a heart attack without chest pressure,” says Dr. Nieca Goldberg, medical director for the Joan H. Tisch Center for Women’s Health at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York. Dr. Goldberg says symptoms in women can include pain in the lower chest or upper abdomen, nausea, jaw pain, lightheadedness or fainting, upper-back pressure or extreme fatigue.

When Karen Feit, a Hadassah portfolio council member, first experienced chest pains in the spring of 2014, she assumed they were caused by stress. The pains were not sharp or severe—classic symptoms of a heart attack—and she had recently lost her job.

That July, on the way home from Hadassah’s 2014 national convention in Las Vegas, the sensations came back and, once more, she attributed them to anxiety and even post-convention exhaustion. Then Feit remembered something she had learned from Every Beat Counts: Hadassah’s Heart Health Program, that women’s heart disease symptoms differ from men’s. Feit went to her local emergency room and, within 30 minutes, she underwent an EKG and had a stent implanted. She had, in fact, suffered a heart attack without realizing it.

Even though cardiovascular disease and stroke are the cause of one out of every three women’s deaths in the United States, women often assume the symptoms are caused by less life-threatening conditions—from acid reflux to anxiety and even normal aging. “They do this because they are scared and because they put their families first,” Dr. Goldberg says. “There are still many women who are shocked that they could be having a heart attack.”

Studies also show that medical providers are more likely to attribute women’s pain symptoms to psychological causes and men’s symptoms to physical or neurological conditions.

Bonnie Tucker had repeatedly complained to medical professionals about numbness in her feet and legs—a common indicator of MS—but none of the doctors she saw had a medical explanation for her symptoms. In November 1988, Tucker’s problems worsened and her then-husband, Ed, a lawyer, called a neurologist client who ran blood tests and reported the diagnosis.

“No one ever suggested multiple sclerosis before,” Tucker says. “Doctors would say, ‘Well, you’re pregnant so you’re tired, or you have children so you’re tired.’” In fact, recalls Tucker, about a year before her diagnosis, she complained to her doctor about numbness in her legs, and he said, “Just don’t wear high heels.”

“Even though MS is such a serious condition, I was so happy to have that diagnosis because it meant I wasn’t going crazy,” says Tucker, whose disease is now under control through injections she gives herself several times a week.

Elisabeth Finch, 35, a Los Angeles-based writer for the television show Grey’s Anatomy, penned a story for Elle magazine last year about an orthopedic surgeon who dismissed the pain in her knee and joked that he “specialized in neurotic Jewish women.” Finch went to another surgeon, who operated on the cartilage in her knee and found a tumor—and then more on her spine and kidneys. Finch has been through chemotherapy and still undergoes regular checkups to monitor a cluster of cancer cells in her spine.

Indeed, the illnesses these women are experiencing—MS, heart disease and cancer—are among the women’s health issues most critically in need of research, according to Nancy Adler, Ph.D., a social psychologist and former chair of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Women’s Health Research, which published the 2010 report “Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls and Promise.”

She also points to other research needs, including depression and autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

The National Institutes of Health first announced a policy to include more women in clinical trials in 1986. Efforts were expanded after a 1990 report by the General Accounting Office—Congress’s research arm—found little change in medical research in the previous four years. Since then, women gradually have been included in trials, and a number of offices that fund and share information on women’s health have been created at major federal agencies.

“A key reason why progress has been slow is that the male model was the default, even down to the animal research, since women’s bodies were seen to be more complex because of the menstrual cycle,” says Adler, director of the Center for Health and Community at the University of California, San Francisco.

“A key reason why progress has been slow is that the male model was the default, even down to the animal research, since women’s bodies were seen to be more complex because of the menstrual cycle,” says Adler, director of the Center for Health and Community at the University of California, San Francisco.

Following the release of the 2010 report from the Institute of Medicine, now known as the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, Adler’s committee conducted a workshop for medical journal editors, encouraging them to report separate data for men and women. “We got pushback on expense because of how many people would be needed,” she says. “It’s a tradeoff. It will be more expensive, but we will have more data on whether treatments work for both men and women. And we need that because we have been systematically shortchanging women.”

Even as efforts lag, newer issues have emerged, such as the specific needs of gay and transgender women, says Dr. Susan Wood, director of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and former director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Women’s Health. “We need to ask more sophisticated questions, and there is much more to be done at the clinical and policy levels,” she says.

In a 2014 article in Nature magazine, NIH head Dr. Francis Collins and Dr. Janine Clayton, head of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, emphasized the value of including male and female animals in early research. They noted that including women in clinical trials had produced much-needed information, such as how preventive effects of low-dose aspirin differed depending on age and gender, and how different doses of a popular insomnia drug are needed in women and men. However, Drs. Collins and Clayton wrote in the Nature article that there has “not been a corresponding revolution in experimental design and analyses in cell and animal research—despite multiple calls to action.”

To help bring about new research modalities, the NIH is requiring funding applicants to include male and female cells and lab animals in proposed pre-clinical studies, unless they can show why they are not needed.

Alina Salganicoff, vice president and director of Women’s Health Policy at the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, a health policy research institute in Washington, D.C., pointed out that also critical to the knowledge base is finding out when there are no differences between men and women. “Without the evidence base, we’re falling short, and in the long run it could affect quality of care and health outcomes,” she says, adding that such evidence is critical to determining insurance coverage.

In January 2016, the FDA released the Women’s Health Research Roadmap. The plan outlines seven priority areas that will advance understanding of women’s health issues, from safety and clinical study design to data analysis and emerging technologies.

Meanwhile, hadassah’s Coalition for Women’s Health Equity is planning a one-day conference in Washington, D.C., to coincide with National Women’s Health Week in mid-May. “We plan to hit the ground running in 2017—engaging the 115th Congress in our work to address inequities in quality of care, funding, support and gaps in women’s health awareness,” says Hershkin. “We are also hoping to shift public conversation around women’s health by expanding the focus to health and wellness throughout a woman’s entire lifespan.”

Legislation currently being considered by Congress could move women’s health research forward if it is passed.

The Research for All Act of 2015 would provide statutory authority to the NIH’s new policy on the inclusion of female cells and animals in pre-clinical research as well as mandate consistent progress reports.

The Advancing NIH Strategic Planning and Representation in Medical Research Act would support the NIH’s new pre-clinical policy, greater inclusion of women in later-stage research and increased attention to research on pregnant women and sexual minorities.

Good ideas also need to move from thinking to practice, say advocates. “We need to figure out who will be implementing the many laws that have been created to help improve women’s health equity,” says Linda Goler Blount, head of the Black Women’s Health Imperative.

Achieving equity in medicine has a long way to go, Hershkin acknowledges, “but that is why we convened the coalition—to combine our power and amplify our voices, to help us achieve more together than we could working on our own.”

Fran Kritz is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply