American View

Personality

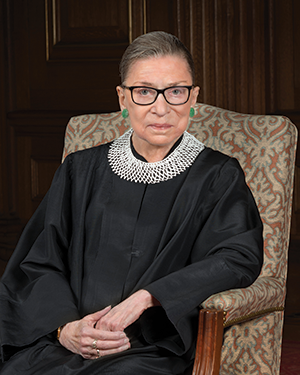

RBG: Supreme Champion of Justice and Civil Rights

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, icon and iconoclast, is not above getting starry-eyed herself. In her chambers, chock-full of photographs, artwork, awards and memorabilia, she singles out a picture of herself with Placido Domingo at Harvard University’s commencement in 2011, when they both received honorary degrees. Though she knew they would be seated next to each other, she wasn’t told that the opera superstar would be serenading her—an opera devotee—with an adaptation of Verdi’s “Celeste Aida.”

“That’s a portrait of a woman in ecstasy,” she says. On a personal level, the degree was a restitution of sorts for the Harvard diploma she gave up 57 years ago when she transferred to Columbia University in her third year of law school to be with her husband, Martin, who had taken a job as a tax attorney in New York City. On a broader level, she points to the graduation speaker seated in the first row of the photo, Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, as “a sign of the changing times.”

A fierce champion of justice, gender equality, individual dignity and inclusivity, Ginsburg, 83, has vigorously shaped those changing times. As a co-founder and advocate at the American Civil Liberties Union Women’s Rights Project from 1972 to 1980, she argued six landmark cases in front of the Supreme Court, winning five. In her 23 years on the Supreme Court bench, she has issued both majority opinions as well as vehement dissents against pay, race and gender discrimination and in favor of affirmative action, voting and reproductive rights. “To be part of the decision-making of this court—that is an incomparable privilege,” she says. “It’s by far the hardest and best job I’ve ever had.”

In the preface to her new book, My Own Words, Ginsburg writes that she was fortunate to have ridden the feminist wave. The book features a selection of writings and speeches on wide-ranging topics, from gender equality and Jewish identity to law and opera, and is co-written with Mary Hartnett and Wendy Williams, law professors whose authorized biography of Ginsburg is in the works. Also forthcoming, Natalie Portman will portray her in the film On the Basis of Sex, about a 1971 case Ginsburg litigated.

Among her heroes, she counts civil rights activist and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, whose chambers she inherited. A silver mezuzah adorns her door, adjacent to a hall closet holding three robes and a collection of collars (jabots) that she varies depending on whether she votes with the majority (“appropriately glittery”) or dissents (beaded black velvet). The white one she wears most often is a gift from South African activist and jurist Albie Sachs.

Dressed in blue slacks, a blue-and-white shawl over a patterned blouse and blue stud earrings—with the legendary scrunchie holding back her hair—Ginsburg exudes a polite demeanor and diminutive appearance, which belies her strong and fearless voice on the court. In 2013, when the court struck down portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Shelby County v. Holder, her outspoken dissent captivated young social media activists, who posted an Instagram image captioned “Can’t Spell Truth without Ruth” and dubbed her “Notorious R.B.G.” Her reputation has spawned T-shirts and tattoos, coloring books and Halloween costumes as well as a best-selling book (Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik).

The justice is bemused. she describes herself as shy and quiet, and sober on the bench. But she loves a good joke: Her husband and Supreme Court best buddy Antonin Scalia, both deceased now, were “funny fellows,” famously able to make her laugh.

She is deadly serious about the Constitution and carries a copy in her handbag. In noting that the 14th Amendment includes her favorite clause—“Nor shall any state deny to any person the equal protection of the law”—she launches into a short lecture: “We start the Constitution with the words, ‘We the people.’ Think back to who we were in the beginning. I wasn’t there. No person held in human bondage was there. Native Americans weren’t there. But the genius of the Constitution is that in over the two centuries that we’ve existed, ‘We the people’ has become more and more expansive and has come to include the left-out people, including women. So I celebrate what the Constitution has become over the years.”

Her admiration for the Bill of Rights stretches back 70 years to the first piece she ever published, in the newspaper of P.S. 38 in Brooklyn, N.Y., where she grew up. The article, which appears as the first entry in My Own Words, describes five great documents: the Ten Commandments, the Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence and the United Nations Charter.

Her parents—Celia, a homemaker, and Nathan, a furrier who later worked in a men’s clothing store—were both products of immigrant families that escaped Eastern Europe. Her mother instilled in her a love of reading and saved $8,000 for her daughter’s college education.

Ginsburg’s childhood, however, was marred by loss. Her older sister, Marilyn, died of meningitis at age 6. Her mother suffered with cervical cancer for years and died the day before Ginsburg’s high school graduation. When President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg to the Supreme Court in a Rose Garden ceremony in 1993, she responded with a tribute to her mother, “the bravest and strongest person I have known.” She frequently quotes her mother’s favorite

pieces of advice: Be a lady—meaning, don’t be distracted by useless emotions like anger and envy—and be independent.

As a young woman, she devoted herself to academics, functioning on minimal sleep (as she does to this day) but also making time to be active in student government, play the cello and twirl the baton.

“She was popular but was not what you would think of as a popular girl,” says one of her oldest friends from high school, Ann Kittner, 84, of Rhode Island. “She had a quiet, magnetic personality. She wasn’t outgoing, but there was something inner that people sensed and felt. She was capable and guarded, warm but not effusive, self-confident but not rash.”

This past July, in her condemnation of G.O.P. candidate Donald Trump, Ginsburg deviated from her usual restraint, drawing criticism regarding her impartiality as a justice.

Though she is not religiously observant, Ginsburg stresses that Jewish values inform her identity. Several works of art in her chambers frame the biblical words, Tzedek, tzedek tirdof (Justice, justice you shall pursue). “Being Jewish is part of what I am just as being a woman is part of what I am,” she says, adding a caveat: “I can’t say that I decide cases one way or another because of my Jewish heritage.”

She considers one of her “big achievements”—with the aid of Justice Stephen Breyer, who is also Jewish—to be getting the court not to sit on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur. “We had the great Yom Kippur conference,” she says. What persuaded former Chief Justice William Rehnquist was the contention that some of the lawyers who would come before them would have to choose between observing their religious faith and presenting the arguments they had been practicing for months.

A life member of Hadassah (a gift from her mother-in-law), Ginsburg says she wished she knew as a teenager about a letter written by Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold—one of seven daughters—to Hyam Peretz, who offered to say Kaddish in Szold’s stead following her mother’s death. “It was a pitch-perfect putdown, but she did it so eloquently. She said, ‘I understand how kind your offer is, but my mother would want me and my sisters to say the prayer.’”

Another Hadassah connection includes Ginsburg’s regular Supreme Court appearance with participants of Hadassah’s Swearing-In Program, organized for Hadassah members who are lawyers by the Center for Attorneys Councils.

Earlier this year, Ginsburg co-authored a feminist reading of the Passover story with Lauren Holtzblatt, associate rabbi of Adas Israel in Washington, D.C. Their interpretation highlighted the pivotal role of five brave but “invisible” women.

“Being part of a people in the shadows for so long has given her the mission to uplift and give voice to others who are downtrodden,” says Holtzblatt. “That’s an important thread for her.”

Ginsburg’s biography is replete with “firsts” and “fews:” First in her class at James Madison High School in Brooklyn; first at Cornell University, with a bachelor’s degree in government; one of only nine women of 500 students at Harvard Law School; first female member of Harvard Law Review; first in her class at Columbia Law School; second woman to teach law at Rutgers University in New Jersey; first female professor at Columbia Law School to earn tenure; second female and first Jewish woman on the Supreme Court. In 2013, she was the first Supreme Court justice to officiate at a same-sex wedding. Now the senior justice among the triumvirate of women, she says she plans to stay as long as she can do the job “full steam.”

Along with all her professional distinctions, Ginsburg is proud of her familial ones as well. In their 56 years of marriage, she and her husband supported each other wholeheartedly, with Marty taking on all the culinary duties in the home. Early on, she helped him through law school as he overcame testicular cancer and balanced her own studies with caring for their newborn daughter, Jane, who is now a professor at Columbia Law School. Son James is founder and president of a classical music recording company in Chicago. She is now a grandmother of four.

Despite her stellar achievements, Ginsburg could not find a job upon her law school graduation in 1959. No one would overlook her triple “handicaps:” She was a woman, a mother and a Jew. Finally, Federal District Court Judge Edmund Palmieri hired her. After her two-year clerkship, she began dividing her time between New York and Sweden, which had begun to take an interest in freeing men and women from gender roles. She learned the language fluently enough to do the research for her book Civil Procedure in Sweden in 1965.

Ginsburg served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, appointed by Jimmy Carter in 1980, until she joined the Supreme Court.

Neither her age nor her health issues nor losing her beloved husband to cancer in 2010 has slowed her down. She herself recovered from cancer twice without missing a day of court, works out twice a week in the Supreme Court gym, watches the evening news while on the elliptical and does 20 pushups a day. Her apartment at the Watergate is across from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, home to the Washington National Opera. She often visits backstage and has been onstage three times as a super, the opera equivalent of an extra.

Her portrait on the cover of My Own Words is far from the rapt “woman in ecstasy” on her mantel. Her solemn, penetrating demeanor befits the focus of a change-maker, one who continues to deliberate the serious issues of our times.

Rahel Musleah, a regular contributor to Hadassah Magazine, also runs Jewish tours to India (explorejewishindia.com).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Janet Ruth Heller says

This is a great article about one of my favorite Jewish women. Thank you for publishing this! In the 1970s, I co-founded the University Feminist Organization at the University of Chicago with Ruth Bader Ginzberg’s daughter Jane. Jane often talked about her mother, who was then an important feminist lawyer. I was delighted when RBG rose to become a Supreme Court Justice.

Best wishes for 2017!

Janet Ruth Heller

Author of the poetry books Exodus (WordTech Editions, 2014), Folk Concert: Changing Times (Anaphora Literary Press, 2012) and Traffic Stop (Finishing Line Press, 2011), the scholarly book Coleridge, Lamb, Hazlitt, and the Reader of Drama (University of Missouri Press, 1990), the award-winning book for kids about bullying, How the Moon Regained Her Shape (Arbordale, 2006), and the middle-grade book for kids The Passover Surprise (Fictive Press, 2015).

My website is http://www.janetruthheller.com/

bev morse says

more than marvelous. no, just marvelous.

Andrea Andrews Ventris says

Thank you for this article about one of the most accomplished women in American history. I was truly touched by her story. I am grateful for her lifetime commitment to women’s issues.

My mother also endured the “triple handicap” upon law school graduation in 1968, to become a state Court of Appeals judge at age 38. The story of Judge Ginsburg has given me even greater insight and appreciation.

Jacqueline L. says

Wonderful article about a wonderful person. I have the pleasure and privilege of knowing her personally, because my mother (of blessed memory), a lawyer herself and professor of constitutional law toward the end of her working life, became her friend after RBG was appointed to the Supreme Court. Note: In the end, it wasn’t Natalie Portman who played the young RBG in the movie, “On the Basis of Sex.” Felicity Jones was the actress who starred, with Armie Hammer as Marty Ginsburg.