Arts

Feature

The Gloriously Anxious Art of Roz Chast

In many of the cartoons in her graphic memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Roz Chast draws herself as frazzled and harried, her eyes crazed behind off-kilter glasses, her mouth a squiggled black hole and her blond hair frizzing wildly with her emotions. The book, after all, is the story of her parents’ aging and passing almost 10 years ago, and of her maddening relationship with them.

Chast, 61, has built her reputation on chronicling the anxieties, absurdities and simple joys of contemporary life in her wry, neurotic style that often seems decidedly Jewish. She was 23 when her first cartoon was published in The New Yorker and, since then, over 1,200 of her cartoon commentaries and 18 covers have appeared in the magazine. She has also created cartoons for Redbook, Scientific American and other publications. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, which has won a host of honors, will be released in paperback this fall after its initial 2014 publication. A recent exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, “Roz Chast: Cartoon Memoirs,” featured more than 200 of her works. Several children’s books and nine collections augment her prolific output.

At her home in Ridgefield, Conn., Chast is a little calmer than her cartoon persona. Two of her three loves—art and birds—are immediately evident. Her unpretentious and comfortable surroundings are decorated with craft projects from origami to hand-painted eggs, and her art and cartoon collections—works by Helen Hokinson, Jules Pfeiffer, Saul Steinberg and more—even extend into the bathroom. Casually dressed in jeans and a purple shirt decorated with blue hummingbirds, she apologizes for the holes her two pet parrots, Jacky and Eli, have pecked in her beige living-room sofa. They squawk intermittently from their cages nearby, and she calls to them, “Hi baby, I’m here, I’m here.”

“We call across the jungle sometimes,” she explains.

The urban jungle—New York—is her third passion and the subject of many of her cartoons. She moved to Connecticut 20-plus years ago to raise her two sons—Ian Franzen, 29, and Pete, 25—with her husband, writer Bill Franzen, but maintains a pied-à-terre on the Upper West Side.

Chast enthusiastically brings out her latest project, a small embroidered tapestry of horses with the word “neigh” repeatedly stitched—imperfectly. “Uniformity and perfection are not my highest values,” she says. Her art, too, features distinctive shaky lines. Those imperfections, in art and in life itself, are the essence of her cartoons.

Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor for The New Yorker, calls Chast’s style “primitive, sophisticated, playful, whimsical, intensely personal and completely attuned to her subject matter.” Chast, he says, “is the pre-eminent New Yorker cartoonist of the late-20th and early-21st century and has an integrated body of work that transcends any publication.”

Subway Sofa, a large mural she created for “Cartoon Memoirs,” mirrors her New York-centric view. A motley group of people crowd together uneasily on one of Chast’s ubiquitous sofas, a lamp-lit, diamond-patterned wallpaper behind them. Yet this domestic scene takes place on a subway train, where bombastic ads shout, “Buy This Soda, It’s Life-Changing,” and the train’s destination is marked, “The Unknown.”

Chast juxtaposes the “familiar and the terrifying,” says curator Frances Rosenfeld. “Her blend of discomfort and coziness reflects a complex voice that strikes many notes at once.” Chast’s style is “deceptively approachable,” Rosenfeld adds. “There’s something affectionate and sympathetic about how she draws people. It’s her genius to make it look like she’s just dashed it off, but it’s actually very well thought out.”

Though her cartoons are not autobiographical, everything is fair game. She pours all her “anxieties, fears, superstitions, failures, furies, insecurities, and dark imaginings—the kit and caboodle of her psyche” into her work, writes New Yorker editor David Remnick in the introduction to Chast’s opus, Theories of Everything: Selected, Collected, and Health-Inspected Cartoons, 1978-2006. It is her “gift for comic invention that makes them funny.”

Nowhere is this truer than in Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? Chast records the decline of her parents, Elizabeth and George Chast, and her role as an only child with the responsibility to care for them. She reveals her thoughts uncensored: When returning to Brooklyn for the first time in 11 years, she muses that she had done a pretty good job of avoiding her old neighborhood and fantasizes of her parents, “Maybe they’ll both die at the same time in their sleep…and I’ll never have to ‘deal.’”

Her father, a French and Spanish high school teacher who spoke Italian and Yiddish and loved words, was kind and sensitive, a dilly-dallier with chronic anxieties, she writes. Her mother, in contrast, was a critical and uncompromising perfectionist who once wanted to be a concert pianist. When she got angry, she didn’t hesitate to deliver what she called “a blast from Chast.”

Chast wrote the book to remember her parents. “The more they are gone from my life and the older I get, the easier it is for me to have empathy with them,” she says. The book seeks to strike a universal chord. “This is the first time I feel that the things I was saying were not just about people who live in the New York area. It surprised me.” She hopes the book will raise awareness of the critical issues of aging. Some situations her parents experienced were so appalling—for instance, the high cost of assisted-living facilities—that, she says, “I’d like this to be different if I get to be that age.” Both lived well into their 90s.

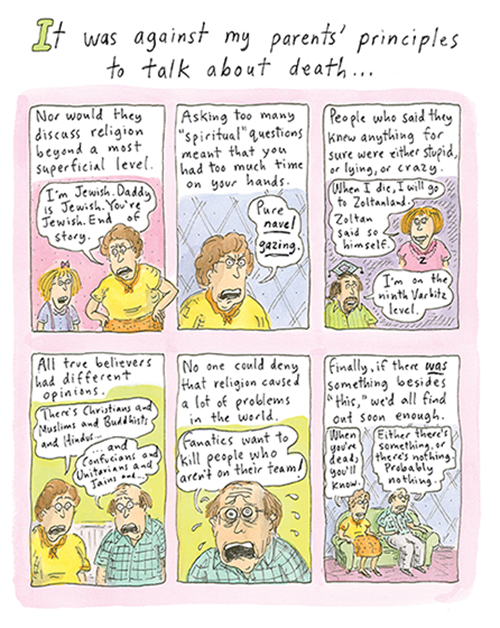

Chast details her Jewish background from the first pages of the memoir. Her grandparents on both sides were Russian, and many members of her family perished in the Holocaust. Judaism was taken for granted, Chast says, pointing out a cartoon in which her mother, arms akimbo, announces, “I’m Jewish. Daddy is Jewish. You’re Jewish. End of story.”

She recalls that her mother belonged to Hadassah and B’nai B’rith and there was a mezuzah on the doorway of their home. Far more than a love of materialistic things, her parents imbued in her the values of conversation, ideas and music. Her mother also had a talent for telling jokes, hosting dinner parties at which joke-telling was a highlight. Chast imitates the conversation, changing and raising her voice: “‘O.K., everybody, I heard a new one. A guy goes to the doctor, blah blah blah,’ and then they would all laugh.”

Chast’s cartoons are sometimes overtly Jewish; sometimes more subtly so. In one titled “Oy!” a jar labeled “Grandma Yetta’s Gefilte Fish” shows a jovial elderly woman shrugging as she says, “What’s in it? Don’t ask.”

Chast’s art is “Jewish” in the tradition of distinct New York cultural voices like Nora Ephron’s that find humor in angst and anxiety, says Rosenfeld. “She weaves together text and image to illuminate the inner state of her characters, making the case that neurotic is not only extremely funny, but also totally normal.”

Mankoff adds that the Jewish layer derives partly from Chast’s exploration of a world that is not especially welcoming. “She looks at a topic every which way to find out the things about it that are threatening or worrisome and annoying so that you can figure out a way to wrap your mind around it, and it becomes less so. She does that through thinking, through a combination of the rational and irrational—and that’s where humor lies.”

Chast says she has loved cartoons ever since she devoured Charles Addams’s darkly humorous work (The Addams Family) as a child. At an even earlier age, her parents would keep her occupied at restaurants by giving her pencil and paper.

Because cartooning was not thought of as “real art,” Chast majored in painting at the Rhode Island School of Design. But, she acknowledges, she was not a very good painter and reverted to drawing after she graduated. She moved to New York and dropped off samples of her work at various publications, including The New Yorker. “Little Things”—a loose collection of objects described by nonsense words—was accepted immediately with a note from the cartoon editor to come back every week. “This was a shockeroo, the most amazing thing that ever happened to me,” she says.

At the time, only one other New Yorker cartoonist was female. A role model for other female cartoonists today, Chast has learned the craft of juggling work and family, and often examines the interactions between mothers and children. Her 2008 cartoon “Doris K. Elston” offers this tribute: Below a statue of a woman with a briefcase the inscription reads, “Brain Surgeon. Professional Model. Artist. Lawyer. Plus Mother of Four.”

What’s courageous for Chast is routine for others. On her website, she depicts herself as a 9-year-old engrossed in a tome dubbed The Big Book of Horrible Rare Diseases. In fact, “big-time medical anxiety” remains a debilitating issue—she hasn’t had a physical in over 25 years.

Chast submits a batch of six to eight cartoons to The New Yorker every week. Of those, the magazine “hopefully” chooses one. File cabinets in her second-floor studio are filled with “rejects” that she sometimes redraws and resubmits. Above the tools of her trade—pens, paintbrushes, scissors and a light box—she has tacked up pictures her children drew when they were young.

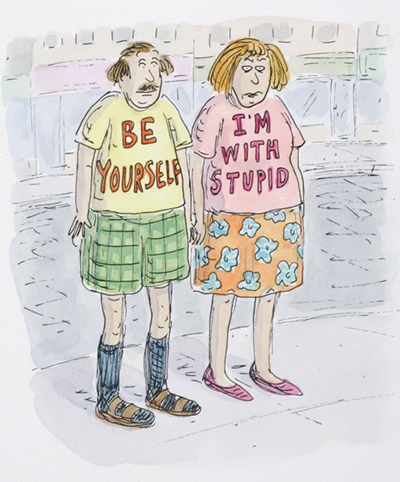

A favorite Chast scenario is the disorientation a New Yorker experiences in suburbia. But no matter where her characters are, they struggle to make sense of a perplexing world. “No-Action Comics” shows six worried people in a grassy field with zigzagged balloons overhead: “Mull!” “Ponder!” “Fret! Fret!” “Obsess!!!” “Dwell!” and “Stew!” Fans of Chast’s work can add one more balloon: “Laugh!”

Rahel Musleah, a regular contributor to ‘Hadassah Magazine,’ also runs Jewish tours to India.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Mike Rhode says

Pfeiffer is actually spelled Feiffer

John Banka says

Russian grandparents? Or where they Polish and counted as Russians due to the Russian occupation of a part of Poland until 1918? thank you