American View

Personality

Health + Medicine

Personality

A ‘Champion of Change’ for Cystic Fibrosis

Emily Kramer-Golinkoff settles into the sofa in her parents’ den in suburban Philadelphia, props her laptop on the table in front of her and hits the switch that starts the afternoon routine critical to her survival. Her slender torso is strapped into a black vest attached by two narrow hoses to an airway-clearance machine designed to agitate the gummy mucus in her lungs that impedes her breathing. With the plastic mouthpiece of an electronic nebulizer clasped firmly between her lips, she steadily inhales a mist of antibiotics. This is the second of three palliative procedures she goes through every day to combat cystic fibrosis.

Earlier, she swallowed most of her daily allotment of 30 pills, and she has already jabbed herself with two of the four insulin injections that manage her cystic fibrosis-related diabetes.

The action of the machine sets off uncontrollable spasms of shivering. Yet Emily sits nonchalantly shaking and sucking air as her fingers furiously tap away—answering emails, attending to business and texting with friends.

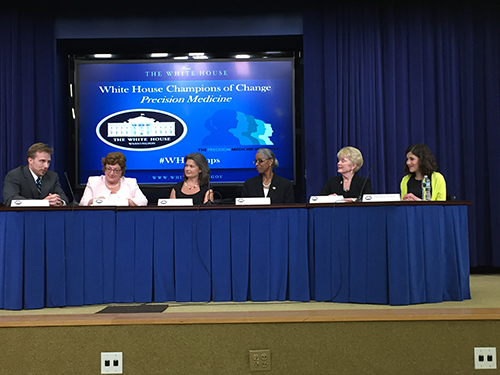

Were you to see this petite, vivacious 31-year-old at any one of her many public appearances—lecturing at a medical conference at Stanford University; making a guest appearance on the CBS television show The Doctors; delivering a TED talk; being honored at the White House; or speaking on the patient perspective at a symposium in Paris—you wouldn’t have the slightest inkling that Emily is gravely ill.

Cystic fibrosis is a fatal genetic disease that affects 70,000 people worldwide—30,000 in America alone. The disease causes abnormally thick and sticky mucus to build up in the lungs and other organs, increasing their susceptibility to life-threatening infections. Emily’s parents, Liza Kramer and Michael Golinkoff, both carry a recessive gene known as the Ashkenazic mutation, one of 1,900 mutations that cause cystic fibrosis. Their children had a one in four chance of inheriting the disease. Emily got hit with two matching mutations. Her younger brother, Coby, was spared as were her twin sisters, Julia and Annie. But Annie was born with severe heart problems and underwent several intricate surgeries in the first week of life that left her medically fragile and unable to speak or move.

Advances in medication have extended the life expectancy for people born with cystic fibrosis to 36 years. Emily, whose lung capacity is down to 35 percent, is already pushing those limits. But that hasn’t stopped her. Talk to her for five minutes and you will realize that she is tenacious, focused and driven by a mission.

That mission is Emily’s Entourage. Five years ago, fueled by a mixture of frustration and desperation, the Kramer-Golinkoff family decided to do something dramatic to keep Emily alive. As her health deteriorated, they realized she would be unlikely to benefit from current cystic fibrosis research. For her to survive, they had to encourage researchers to focus directly on her Ashkenazic genetic mutation. Gathered around the kitchen table one day, the family conceived a plan that morphed into Emily’s Entourage, a nonprofit dedicated to accelerating research for cystic fibrosis.

“We believe in storytelling,” Emily explains. “So we decided to make a video of my story and see if we could inspire people to contribute to our cause.” Coby practically moved into the local Apple store to hone his skills as a videographer and, just before New Year’s Eve 2011, sent out a simple, heart-wrenching video to everyone they knew with a request to donate money and pass it on. The video took off. “We hoped we’d raise $50,000 in a year—and we raised $45,000 in a week,” her mother, Liza, says, still amazed. “We were paralyzed with gratitude.”

To date, Emily’s Entourage, run almost entirely by mother and daughter, has taken in some $2 million in contributions. It’s a small but mighty grassroots organization mostly soliciting online and with events like an annual gala, marathons, yogathons and bike-a-thons.

Not long ago, it would have seemed far-fetched for patients to get involved in seeking their own cures. Not anymore. Today, they are setting agendas, injecting themselves into all aspects of research and forcing science to explore patient-centered outcomes. Like Emily, activists with problems as varied as inherited cancers, vasculitis and multiple sclerosis view themselves as disrupters. Several groups have joined to form independent, patient-powered research networks, a few dozen of which belong to a consortium called PCORnet, the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. These are all part of an emerging trend known as precision medicine, which aims to focus on an individualized rather than a generic approach to curing diseases.

In his 2016 State of the Union address, President Obama pledged $215 million to a Precision Medicine Initiative. The National Institutes of Health is getting $130 million to establish a bank of biospecimens, with the goal of enrolling more than one million Americans to contribute their biological samples to help researchers study individual differences in health and disease. The intent of this pioneering model of patient-powered research is to redesign the traditional one-size-fits-all treatment approach and create therapies that work best for individual patients.

Emily’s Entourage, though not currently aligned with any network, represents this seismic shift in the world of medicine, where patients have become agents for action. In 2015, the White House honored Emily as one of nine Champions of Change for Precision Medicine. Since then, Emily has emerged as a prominent spokeswoman for the movement.

Emily believes she was honored specifically for her efforts to cultivate collaboration and break down walls between the various scientists working in the field of genetic defects known as nonsense mutations. These mutations—the Ashkenazic mutation is one of them—affect millions worldwide. Nonsense mutations are responsible for about one-third of some 2,400 genetic disorders and are typically placed in the category of orphan diseases, an umbrella term for rare or underresearched disorders. Because orphan diseases affect comparatively few people, they have little profit potential—so drug companies shy away from investing resources in cures. But that view is shifting amid growing evidence that discoveries for one nonsense mutation might be useful in treating others.

Emily’s Entourage hopes to accelerate research on genes with a nonsense mutation, particularly in cystic fibrosis, through scientific grants and strategic partnerships with academia and industry. The organization has already distributed funds, from $50,000 to $200,000, to researchers at McGill University in Montreal, The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of California, San Francisco. Emily has also donated cells to existing studies worldwide. A grant to the laboratory at the University of Alabama at Birmingham has helped advance the development of an experimental therapy for cystic fibrosis. The Birmingham center launched a trial in the spring in which Emily is the first and only patient enrolled.

As part of its commitment to encourage researchers to share information, Emily’s Entourage has assembled an impressive scientific advisory board, headed by Kevin Foskett, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Physiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He used his contacts in the cystic fibrosis research community to organize two international symposia over the past several years in Philadelphia, co-sponsored by Emily’s Entourage.

“I never expected to be doing something like this,” says Foskett, shaking his head of thick, shaggy gray hair, “but my daughter went to school with Emily and she got me involved. Emily and Liza are hard to resist.” In his view, Emily has “definitely had an impact. She is passionate, articulate and very knowledgeable about her disease. These assets have been powerful tools in her drive to promote research in nonsense mutations and to get her type of CF on the radar screen of drug companies as well as the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.”

Last fall, Emily resigned from a position she loved at the Penn Social Media & Health Innovation Lab at the University of Pennsylvania to devote herself full-time to her burgeoning nonprofit. “Leaving my job was a really hard decision,” she says with more than a touch of sadness. “Going to work made me feel normal, but I was replaceable there and I’m not replaceable here.”

Her family is close-knit. Friends describe Liza as brave and amazing but she consistently calls herself “lucky.” For a woman with two compromised daughters, Liza has an astonishingly sunny attitude. When the twins turned 21 in April, she and Emily thought nothing of loading Annie’s wheelchair on a plane and taking her to visit Julia, a student at Tulane University in New Orleans, so the twins could celebrate their big day by making the rounds of some local bars. “I keep going because I have no choice,” Liza says. “I have my eye on the prize—a cure for CF. That’s all I want. I do worry and I do get scared, but it never, ever occurs to me to feel sorry for myself.”

Emily’s father has his own take. “Liza does not see the world through rose-colored glasses, but she just doesn’t give in to hopelessness,” Michael says. “She won’t let reality discourage her.”

While cystic fibrosis imposes restrictions on Emily’s life, she makes it clear she has no intention of letting her condition strangle her spirit. She lives independently in a contemporary, one-bedroom apartment in downtown Philadelphia. When she travels, she packs her treatment machinery in her suitcase and sprays sanitizer on her airplane seat. When she went on a Birthright Israel expedition in 2007, the moment the plane landed, Emily made a beeline for the closest bathroom, where she plugged her machines into an electrical outlet and squeezed in a treatment before boarding the tour bus.

Despite 10 hospitalizations while an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, she lived in a campus dorm, served as rush chair of Sigma Delta Tau (her Jewish sorority), graduated cum laude on time with her class in 2007 and went on to earn a master’s degree in bioethics.

She sports a Fitbit on her wrist and tries to clock 10,000 steps a day. “I can’t live in a bubble,” Emily says matter-of-factly. “I was raised not to let my disease define me. My mother, who is my absolute best friend, is all about optimism. When I was in preschool, she’d have my friends come over and make a game out of the chest-pounding we had to do twice a day. Every year, she’d buy me a really beautiful dress that was two sizes too big. That was her way of making me believe I’d grow into it. My health is a priority, but I have others, too. And having my mission is very motivating.”

The clock on Emily’s life is ticking loudly. “I do think about dying,” she acknowledges, “but it doesn’t paralyze me. I worry when the quality of my life will change. And I worry that a breakthrough won’t come in time to help me.

“My biggest fear,” she adds, “is what my death would do to my family, the gaping hole I would leave. But I try to turn this into something positive. I have a big circle of amazing friends. The ability to do my meaningful work is very important

to me. And I have hope. What else is there?”

Carol Saline is a journalist, speaker and author of the photo-essay books Sisters and Mothers & Daughters.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Gloria Feldman says

Goinkoffpersons, you are all amazing. You exude courage and tenacity. You should be cloned.

With tons of admiration and love – gloria

PS – the article was written beautifully, it was poignant and riveting emotionally.

Gloria Feldman says

See above comment.

Leslie Leslie says

Emily and Emily’s family are an inspiration to all of us. May we find the cure and always have the courage, strength and hope!

Carol Tova Newman says

Dear Emily,

Blessings of continued Joy, Passion, Good Health, Wisdom, Friendships and Love in the new year for you and your fabulous family and friends. I’m sending the article about you to another 31 year old CF warrior friend and to my friends whose son is 8 and who vibrates with a smile.

Kol haKavod!

Shana Tova u’Metukah. Shenaht Bree’oot V’Hatzlahah to you all.

thanks to Carol Saline for writing your story.

carol in Astoria, OR

Donna says

Thank you so much for writing and sharing Emily’s story. My brother, Irwin, was born with Cystic Fibrosis. He lived to be 41 years old. He was a beautiful person and well liked also. While working at the Cystic Foundation, a gene was discovered that caused CF and I became quite hopeful that a cure was just around the corner. Unfortunately it is still slow in coming but I too am optimistic that it will come.

Elena says

She is inspiring as is her family. We hope to see a cure in her lifetime and celebrate with her and her family.

Gordon Kaplan says

I knew someone who died from cystic fibrosis. She died in 1982 about a month after her twenty-first birthday. When she was born, I think the life expectancy at the time for cystic fibrosis children was seven years. Forty years before that, most cystic fibrosis children usually did not live beyond their first year. Today, they can live between forty-two and fifty years.

Emily’s story and the story of her family inspired me to write an essay for my Modern Hebrew 201 class.

Gordon