Health + Medicine

Feature

The Past, Present and Future of Cystic Fibrosis

The champagne was flowing at the laboratory in The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto that bright September day in 1989 when researchers announced they had cloned CFTR, the gene for cystic fibrosis. Among the celebrants was Batsheva Kerem, Ph.D., an Israeli geneticist affiliated with Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who was doing her postdoctoral work there. Hopes were high that this discovery would break the bottleneck of what was then a fatal childhood disease and lead to a cure using the burgeoning science of gene therapy.

It didn’t quite turn out that way. The difficulty of replacing a mutant gene in the lungs was far too complicated. But the discovery did open pathways for investigating important new therapies that hadn’t been available previously, meaning that a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis was no longer an early death sentence.

In the past four years, two important drugs have come to market that address the root cause of cystic fibrosis. One of them, Kalydeco, attacks the gene defect by waking up the inactive CFTR protein. But it’s only effective on its own for fewer than 5 percent of patients. A second breakthrough, a combination drug called Orkambi, works by pushing the protein up to the surface of the cell. When administered together, these two drugs have been a major game changer, allowing many with cystic fibrosis to lead longer and more productive lives.

Unfortunately, neither of these drugs corrects the mutation that caused Emily Kramer-Golinkoff’s cystic fibrosis. To behave properly, the CFTR gene requires a complete string of 1,470 amino acids to build the protein that prevents cystic fibrosis. Emily’s problem, the Ashkenazic mutation, is one of 1,900 glitches that interfere with this process. Through her organization Emily’s Entourage, Emily has been advocating for more research on the Ashkenazic mutation and, ultimately, a cure for her cystic fibrosis. One in every 29 Ashkenazic Jews carries the mutation, which is why Jewish genetics centers encourage testing that includes Jewish disorders. The mutation was isolated in 1992 by Batsheva Kerem at Hebrew University, working in collaboration with her husband, Dr. Eitan Kerem, and the cystic fibrosis unit at Hadassah Medical Organization. Batsheva Kerem, who recently joined the scientific advisory board of Emily’s Entourage, first met Emily when Kerem attended one of Emily’s conferences at the University of Pennsylvania. “I was very impressed by Emily and her mother,” she says, speaking by phone from Jerusalem. “They are very brave.”

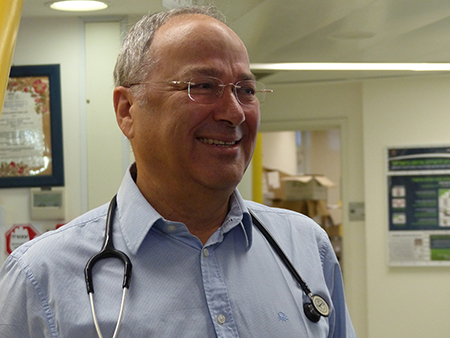

Currently working its way through the pipeline is a drug that might actually help Emily. It is based on what scientists call the read-through concept. It gets around the Ashkenazic mutation by instructing the cell to ignore—or read through—the stop sign and trick the amino acid chain to keep growing. The early work was done by Dr. Kerem, head of pediatrics at Hadassah Medical Center, who, along with his wife, has been conducting cystic fibrosis research for the last 25 years.

“We began by asking whether it was possible to give humans—not lab animals—a drug that would correct the Ashkenazic defect, and we found the answer was yes,” Dr. Kerem says. “But the inhaler drug we created was somewhat limited because of its toxicity.”

Meanwhile, PTC Therapeutics, a biotech company in Plainfield, N.J., was doing similar research and had come up with its own oral, less-toxic compound, Ataluren. When PTC learned about Dr. Kerem’s work, the two labs teamed up to conduct worldwide phase III clinical trials. The results of their double-blind, placebo-controlled study is expected to be released next year. If successful, the next step would be for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to approve Ataluren specifically for cystic fibrosis.

Ataluren has already been approved in Europe and is being prescribed to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy. However the FDA recently refused to review the European data and give the green light for the drug.

“The drugs we are developing do not cure cystic fibrosis,” Dr. Kerem points out. “But, together with other therapies, we now have the possibility that our patients might live long enough to become parents and grandparents and, by then, we will have the cure we need.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Moath Al.refai says

Hello my name is Moaz I have been suffering from cystic fibrosis for a long time and I live in Jordan and we did not have enough medicines