Hadassah

Feature

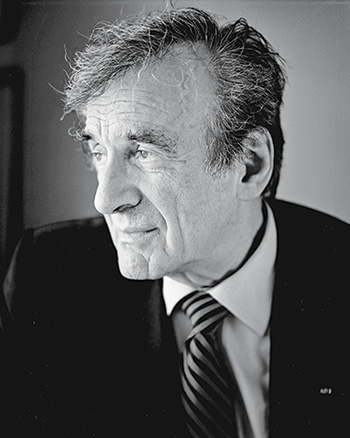

Elie Wiesel, Hadassah Author

Hadassah Magazine mourns the passing of Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor whose experience made him a passionate fighter for social justice and a lover of his people and of the State of Israel. The eloquent author, teacher and thinker was not only a long-time member of the magazine’s editorial board and a judge of its Harold U. Ribalow literary prize. He was also a prolific contributor to its pages for over 50 years. Below are three articles he wrote for the magazine: remembering 9/11; celebrating Israel’s fortieth anniversary; and Warsaw 1943.

Hadassah Magazine mourns the passing of Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor whose experience made him a passionate fighter for social justice and a lover of his people and of the State of Israel. The eloquent author, teacher and thinker was not only a long-time member of the magazine’s editorial board and a judge of its Harold U. Ribalow literary prize. He was also a prolific contributor to its pages for over 50 years. Below are three articles he wrote for the magazine: remembering 9/11; celebrating Israel’s fortieth anniversary; and Warsaw 1943.

The Day We Became a Family

Because of their long history of suffering, following the despicable terror attacks in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, Jews have been asked by their gentile friends: How does one cope with such sorrow and anger? How does one respond to the painful knowledge of so many lives lost? Is consolation possible?

For days and nights, stunned Americans from all social spheres, ethnic origins and religious affiliations have looked forlorn and disoriented. They all wanted to know how such a horror-filled event could happen in the very heart of this civilized agglomeration. How could a few fanatic murders do so much harm in such a short time?

Commentators spoke of a defining moment in the young presidency of George W. Bush. Others mentioned a turning point in our nation’s consciousness. Nothing will be as before. Are we, now, going to view all foreigners with suspicion? Or, at least, board every airplane with fear and trepidation?

United in sadness, people became kind to one another. They waited hours in line to give blood. They shared food and water. In a way, that was their personal answer to the inhumanity of the suicide-hijackers.

What has the wide world learned from the tragedy?

It learned that terror is an international threat to all nations. If left unchecked and not eradicated, it will strike other cities for its practitioners believe not in life but in death. Life—their own and that of others—is of no value to them. Their goal is not to improve civilization but to destroy it. Their god is not God but death.

What then do we Jews say about coping with tragedy? We tell them that it is our tragedy as well. We have the same enemy. There is a link between all suicide fanatics.

We must fight them. Together.

This article originally appeared in the November 2001 issue of Hadassah Magazine.

A Day in May

SABBATH OF INDEPENDENCE

Today is a holiday; let’s not disturb it. Criticizing, arguing, blaming, these can all wait one day. Apprehensions, too. And also wrenching questions. Today, joy alone is in order, since today we are celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Jewish sovereignty, a glorious sovereignty which our people has reconquered in the land of its ancestors.

Forty years, in the Bible, is a generation. This anniversary, then, will bear the stamp of a turning point in history. From now on, things will be different. Nothing will henceforth be as before. The history of Israel is entering into a new era.

That’s what we also used to say 40 years ago I remember and I will continue to remember until the end of my days. I was 19 years old, and I had just discovered hope.

It was a Friday afternoon. I lived cramped up in a small room near the Porte Saint-Cloud in Paris. I had no radio. To find out what was going on in Jerusalem, I went out several times to buy the latest editions of the afternoon newspapers. I would read and reread the Declaration of Independence, David Ben-Gurion’s speech: the first speech by a Prime Minister in the Land of Judea. I would dwell on each sentence, I would repeat certain words aloud, memories and prayers would whirl around in my head all ablaze, children and old people would stretch out their hands to me in a distant dream, buried and hidden: Come, I would say to them, come let us greet the approaching Shabbat, this Shabbat which must never end. This Shabbat of Independence.

A Shabbat in a class by itself—unique; one could feel the neshama yeteira, the additional soul which takes hold of you and draws you toward the highest spheres. The ”Angels of Peace” must have been busy that Shabbat, because the overflowing collective joy of our people was already diminishing. Israel had hardly been born and already its future was in danger. Seven Arab armies were moving forward to destroy it.

The days following I would run from one demonstration to another; I was bent on being together with other Jews. The leanings of the party that had organized the event mattered little; the speakers were singing the praises of Israel—that was enough for me. In Yiddish, in French, in Hebrew, they were declaring themselves to be inextricably bound to the Jewish state, to its fighters and to its citizens, and they were speaking in my name as well.

That is because, for us, Israel represented not a beginning, but beginning anew. That a people was able to pull itself together, to recover so quickly—let us remember, only three years separated the Jewish rebirth from that catastrophe called Auschwitz—was for us a source of both wonder and rapture. Ordinarily, the mourning in which we were immersed ought to have lasted decades and eternities. Without negating that mourning, our people was able to overcome it, to transcend it and then to transform it into an awe-inspiring prophetic project whose principle was faith in Israel and its memory, faith in man and in his right to dignity.

There is nothing surprising about the fact that Israel holds such a central place in Jewish existence, even in the diaspora. Everything that happens there affects us. We participate in its victories and in its crises. When things go poorly there, we tremble, just as we are proud when things go well. Yehuda Halevi was right: The Jewish heart is always in the Holy Land. And Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav, who said: “Wherever I may go, my steps take me to Jerusalem.”

Can you imagine your life without Israel? Without the enrichment we receive from Israel? Remember your first trip to Israel, and you will have the answer.

I remember mine. Summer of 1949. The last night of the crossing, I did not sleep. Standing on the bridge, I was preparing myself for my first impression of Mount Carmel. At dawn I was grabbed by an emotion that was both familiar and unknown. “Here finally is a place where I am surely welcome,” I thought, I had to make an effort not to cry.

I remember my first visit to Jerusalem. I had the impression that it was not my first; I had already strolled through its narrow streets, bathed by an incomparable light. I remember my encounter with the Wall, or rather with myself in front of the Wall; everything in me began to pray—I became prayer. Other encounters, elsewhere; other memories linked to other events, I remember them, all of them. Oh, of course, not all of them were bearers of promise; there were among them others which engendered fear and trembling, but let us not talk of these. Not today.

Today is a holiday. Let us see to it that nothing will cast a pall of gloom over it. Tomorrow it will be different. Today, it is incumbent on us to exercise self-restraint. In a single generation, Israel has passed through so many trials and so many conflicts that it has a right to joy.

And so do we.

(Translated from the French by Joseph Lowin)

This article originally appeared in the April 1988 issue of Hadassah Magazine.

WARSAW ’43

PASSOVER 1943. While preparing dinner, a Jewish woman finds time to read a Hungarian newspaper. “Why did they do it?” she whispers sadly. They: the Jews in Warsaw. They have staged an uprising, according to the news item. “Why did they do it?”

The woman cannot understand their foolish haste: Why provoke the enemy? Why precipitate events? “Couldn’t they wait, just wait peacefully for the war to end? It won’t be long. Why irritate the Germans?” She doesn’t know that waiting is no solution, that the alternative is Treblinka. She has never heard the name.

Poor mother.

In Warsaw, the fighters believe that they can influence the course of history. That an entire generation is following their struggle with anguish and pride. That Jews in America, Palestine and other free countries are knocking at every door, mobilizing every friend and ally to their rescue. And that in Jewish homes, from Washington to London to Johannesburg, people are talking of the uprising and of nothing else.

The fighters are convinced that Jews everywhere are aware of the awesome implications of the event and that they are praying for their survival if not for their victory. When they learn from an English broadcast that their rebellion is known to the world, they shout with joy. Emanuel Ringelblum notes this is in a diary. A wave of hope sweeps through the ghetto on that day. Now that the world is informed, help is bound to come.

Poor dreamers.

Mordecai Anielewicz’s messages are poignant and simple. He appeals to the conscience of mankind, to the heart of his brethren. He describes the desperate battle, the astonishing triumphs. The prospects. The losses. The smood of the combatants, their tactics. The ghetto is resisting; that is the main accomplishment.

Then the ghetto begins to burn; it needs arms and it needs them urgently. It needs help, any help. And encouragement, in any form. Even a few words of praise, of prayer. To assure the warriors that their combat is being witnessed and will be remembered. That their sacrifice will not be in vain. That their messages are being answered: “From beyond the walls we cry with you, we weep over you, we weep for ourselves, too.” A few words to tell the last heroes and defenders of the ghetto that they are not alone.

But they are alone.

Even though the story is being reported, phase after phase, with baffling accuracy. Three days after the outbreak of the rebellion, news about it reaches the capitals of the free world. It is printed with due emphasis in the Yiddish press, carried by all the wire agencies, including the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, published in The New York Times. The factual story tells of the action against “the last 35,000 Jews in the Warsaw ghetto.” Of shooting in the streets. Of house-to-house resistance. “Women and children defend themselves with bare hands . . .”

The reaction? Almost none. Check the back issues of American dailies of the period. Check your own Temple bulletin. How many leaders organized mass demonstrations in Madison Square Garden? How many Jewish spokesmen called on the White House to protest and demand action? How many rabbis devoted their sermons to the subject?

The mood was festive, the Passover holiday unperturbed. This men’s club prepared its annual dinner, that sisterhood committee looked forward to its semiannual fashion show. Drinks, cocktails, dances. One synagogue promised to supply a famous humorist for its annual dinner.

He came. The dinner was a success.

In London, a Polish Hew, a Bundist named Shmuel Zygelboim, despairs. He writes a farewell letter: “…My life belongs to my people in Poland and that is why I am sacrificing it for them.” Also: “My companions of the Warsaw ghetto fell in a last heroic battle with their weapons in their hands. I did not have the honor to die with them but I belong to them and to their common grave.” And then: “Let my death be an energetic cry of protest against the indifference of the world which witnesses the extermination of the Jewish people without taking any steps to prevent it.”

How naïve he was; his suicide went almost unnoticed.

Thirty years later students of history and literature try o explore the doomed world of European Jewry and come up with disturbing questions: Why didn’t American Jewry do something, anything? Why wasn’t there any action undertaken in Palestine to dispatch some help to the besieged ghetto? Why were Anielewicz and his comrades left in such solitude?

A boy reads some pages about the ghetto uprising to his class and remarks: “I am proud.” Then a girl quotes press clippings about the passivity of Jews in America and comments: “I am ashamed.”

What can their teacher say? He can tell them only to read again. And again.

This article originally appeared in the April 1973 issue of Hadassah Magazine.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Lori Weintrob says

Powerful words especially on Warsaw.

QUESTION: In 1968, Wiesel wrote a play that was published in Hadassah’s magazine called: “A Black Canopy, A Black Sky.” It was to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. If you have any information about it, or if you could send a scan of any prologue to the play, please contact me at LRWeintr@wagner.edu. I am researching it. Thank you.