Being Jewish

Commentary

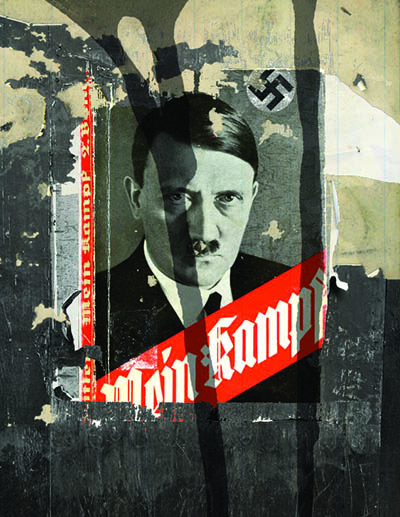

Mein Kampf in Today’s World

For the first time since World War II, the publication of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf has been permitted in Germany. Scholars working with the Institute of Contemporary History Munich–Berlin have put together a two-volume, annotated edition of nearly 2,000 pages—twice the size of the original—that deconstructs the book’s factual errors, lies and distortions in 3,500 footnotes.

Should we be concerned about the publication of the work in the land where it led to the murder of six million Jews? I am curiously indifferent—though not to the rise of the far right in Europe. Nor am I indifferent to the increasing demonization of Jews in Europe, fueled by the inability of many seemingly well-informed intellectuals and political voices to distinguish between opposition to Israel’s policies and the maligning of all Jews.

Mein Kampf has long been available in libraries and online. It also has been published outside of Germany. Obtaining a copy has not been hard, but getting through it is a different matter. It is, quite simply, poorly written and boring.

I am not afraid that Mein Kampf will be read by a new generation of Germans and spur anti-Semitism—though 24,000 copies of the book were sold in the first seven weeks. For those attracted to these views, other works have long been accessible. Sometimes you don’t even need the primary source itself. Few have read the fabricated anti-Semitic work The Protocols of the Elders of Zion from cover to cover, for example, but many have absorbed and internalized its pernicious content.

I am, however, most curious about the reaction of German millennials to Mein Kampf. If I taught in Germany, I would listen carefully to students’ responses. Would they be perplexed that such a mediocre work could persuade its readers, let alone inspire a generation? Young Germans are innocent of the crime, but they are descendants of the perpetrators. They should continue to regard themselves as if they have emerged from tyranny and commit themselves to democracy and pluralism, respect for human rights and dignity and abhorrence of anti-Semitism.

Hitler’s impact was not in the written word but in his charismatic presence, fueled by the anxiety of his time. In pictures, Hitler was not impressive. But in the flesh,he exerted a magnetism that persuaded even sophisticated Germans. Today’s danger, however, is in the amplifications of racial and religious hatred and official policies of exclusion and division. It also stems from the use of social media, which increasingly gives us the capacity to find like-minded people and establish communities of rage.

Perhaps the reason I am most indifferent to the publication of Mein Kampf is because the anti-Semitism of 2016 is radically different than what we experienced 75 years ago. We, the Jewish people, are different today, empowered both in the State of Israel and in the United States—and so, too, is the world. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls said in January in the aftermath of the Paris terror attacks that “France without Jews is not France.”

Because Hitler is dead and the German people are chastened, the Nazi danger is past. Other dangers loom, however, as Psalms (22:17) notes: “…a company of evil-doers have enclosed me.” Those dangers are radical Islam, failed states and terrorism.

But we have many more resources to confront the new threats—if we use them wisely.

Michael Berenbaum is a professor of Jewish studies and director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical and Religious Implications of the Holocaust, at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply