Books

Non-fiction

Till We Have Built Jerusalem

Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Architects of a New City

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 368 pp. $28) Elin Schoen Brockman

Jerusalem embodies the spiritual like no other city. This is partly accident (the light, the heavenly topography). But the look and feel of this mysterious, majestic, fraught, fought-over place—its earthy incandescence—also owes much to the work of British Mandate period architects Erich Mendelsohn, Austen St. Barbe Harrison and Spyro Houris. The three shared, if little else, a passion for local culture and aesthetic traditions that went way beyond the 1918 law prohibiting the use of any building material here except in local Jerusalem stone.

In Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Architects of a New City, Adina Hoffman goes beyond writing history and biography to bring these visionaries, their dreams and their work vividly and poignantly to life. She begins her voyage of discovery on Jaffa Road, pointing out “what I see…” Mendelsohn’s grand, portholed seven-story tower, once a bank, now a government ministry; the main post office by Harrison; and Houris’s pinkish honeycomb of flats and shops. Hoffman also hints at “what I don’t see”—at where she will take us via digital archives, paper trails and visits to building after charismatic building. In her book, she digs deep, but also casts her net outward to pull in dozens of fascinating supporting characters—like David Ohannessian, the great Armenian tile-maker brought in by the British to help renovate the deteriorating Dome of the Rock, a project that devolved into a political morass, as so many projects in Jerusalem always have done.

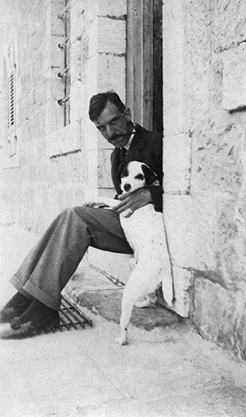

But Ohannessian’s Ottoman tile work became a hallmark of the Jerusalem look, from the trilingual Old City street signs to the exotic mansions (one has become a Palestinian cultural center) that are practically the only clues left to the existence of the possibly Arab, possibly Greek Houris. Throughout the book, Hoffman pursues Houris’s “ghost,” finding traces of a character who could have stepped from the pages of a Lawrence Durrell novel.

Harrison, a relative of Jane Austen, was the supremely British chief architect of the British Mandatory Public Works Department. He was Beaux Arts-educated but Byzantine- and Ottoman- inclined and also could have sprung from Durrell’s imagination—or from his actual experience, since the two men knew each other.

But the personality that dominates the book is the Jewish Mendelsohn, who was one of the greatest architects of Weimar Germany. He fled to Palestine with his wife, Luise, in 1933. The Rehavia windmill became home and his studio. The story of how his plans for Hadassah Hospital and Hebrew University materialized on Mount Scopus—amid the violence that led to the partition—describes how a handful of idealists, including then-Hadassah President Rose Jacobs, quashed myriads of obstacles—a theme that threads through the book, for it could be Jerusalem’s mantra.

Aesthetics vying with politics. Construction vs. destruction. Hope vs. despair. Hoffman beautifully captures the romance of the Hadassah complex-in-the-making, its symbolic, as well as pragmatic, role in the rebirth of Jerusalem, the impact of which was not lost on its architect and his wife. Sometimes, Hoffman writes, they would drive with their dinner guests “up the winding road to Mount Scopus, where they’d wander in the moonlight over the building site. Then—“deeply moved” and overcome by “a mood of reverence and gratefulness” (as Luise would write of one particularly charmed pre-dawn outing) – they would watch the sun rise over the city.” Hoffman ends her stories (there are enough here for several books) in the cemetery on Mount Zion, searching through the rubble for the burial place of Spyro Houris. “Still looking,” she writes. As if to say: all is not lost. At least not for the moment.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply