Wider World

Feature

The Jews of Sosúa, Saved by Reverse Discrimination

My journey to Sosúa began with an email. It was from a travel service, inviting me to “Visit Sosúa! Discover this paradise founded by European Jews!”

The story of Sosúa—the large oceanside town where the Dominican Republic government provided Jewish refugees with land and resources—is unique, even among the annals of Holocaust history. The message felt customized just for me—a daughter of two Holocaust survivors, a writer looking for a new subject, a Spanish-speaker and infrequent yet devoted fan of Caribbean beaches.

Between 1940 and 1942, several hundred German and Austrian Jews landed on the shores of La Republica Dominicana, the Dominican Republic. The refugees had been in transit for years, in refugee, detention and labor camps and training centers. Most of them had never even heard of the island before and would certainly never have chosen it, even as a temporary home, except no other country was willing to admit them.

While recent years have seen a documentary on Dominicans and Jews that includes mention of the Jewish history of Sosúa; a virtual Sosúa museum, sosuamuseum.org; and a few news articles, the Jewish history of Sosúa is still one of the lesser-known sagas of World War II.

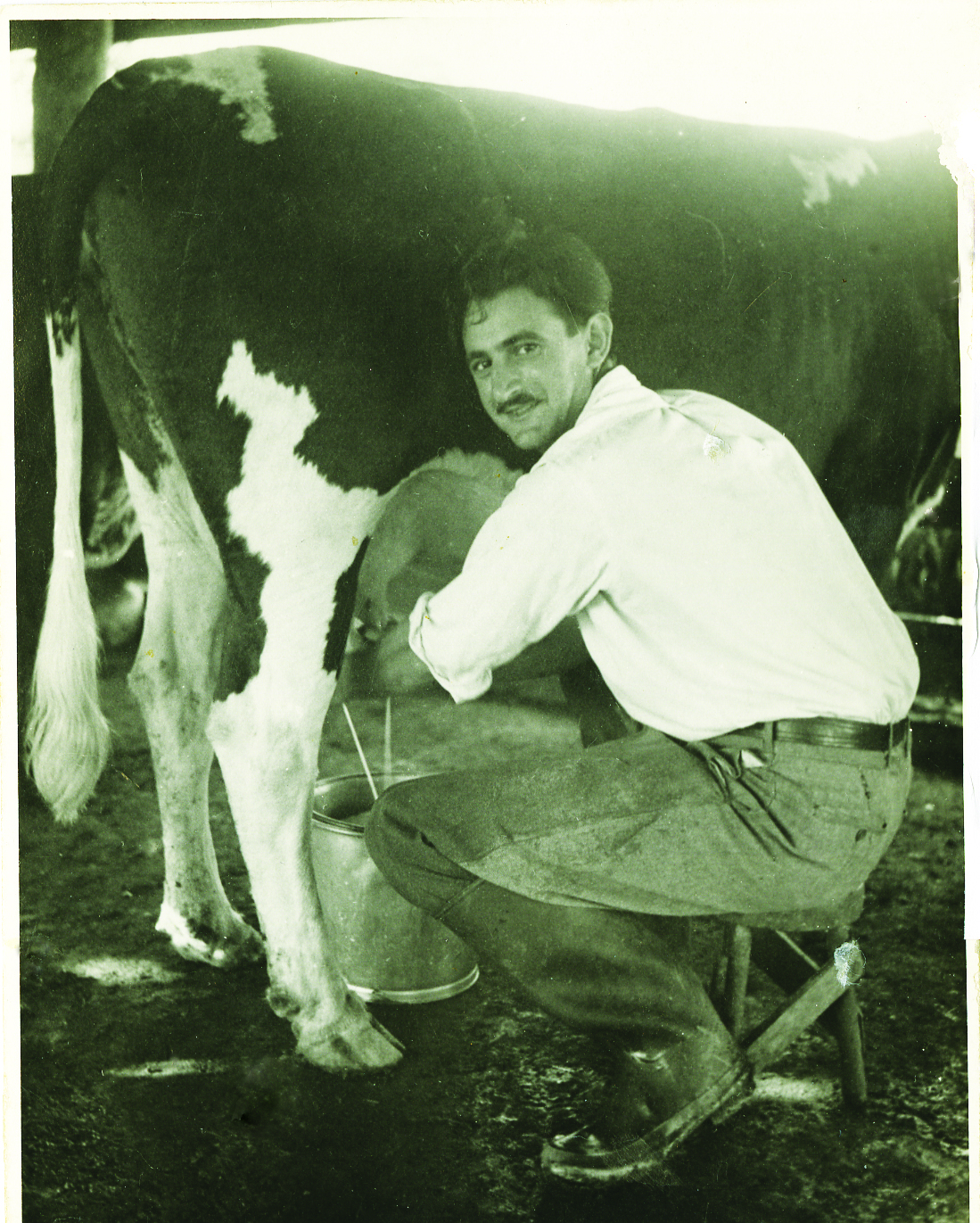

“The Jews brought the world to us,” says Don Luis Hernandez, a 90-year-old resident of the Sosúa neighborhood of Los Charamicos, spreading his hands wide. The refugees transformed this part of the island, building a medical clinic, paving roads and creating a kibbutz cooperative of around 50 farms that helped Sosúa become the cheese and dairy capital of the country.

I had the opportunity to see some of those transformations myself, or at least the remnants of them.

Within months of that email, I embarked on an adventure, fueled by lifelong questions about those who, like my parents, found a way to escape the conflagration in Europe. My questions were now focused on a sliver of Holocaust history set in the tropics. Along with a swimsuit and sunscreen, I carried my version of beach reading—Tropical Zion: General Trujillo, FDR, and the Jews of Sosúa (Duke University Press), Allen Wells’s comprehensive and insightful text. The book, along with the excellent Dominican Haven: The Jewish Refugee Settlement in Sosúa, 1940-1945 (Museum of Jewish Heritage) by Marion Kaplan, which I read after returning from my trip, became an invaluable reference library.

In addition to the language, culture and climate, Wells explains, there was a great deal that the émigrés didn’t understand about the Dominican Republic (often called the DR). The refugees were in their twenties and thirties and in good health; most were single and men outnumbered women. They had all been interviewed and screened by the newly formed Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA), created with the assistance of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and chosen for their stamina, adaptability, social skills and youth. What they encountered was probably more exotic than they had imagined. In addition, many of the Jews were city folk; given the chance to escape from Nazi-dominated Europe, they had exaggerated their farming know-how. The irony of the settlers’ value to the Generalissimo of the DR, Rafael Trujillo, was, in fact, their white skin.

These least desirable noncitizens of the reich were now wanted because of their potential for mixing with what Trujillo thought of as a “too-dark” populace. A brutal dictator, Trujillo was responsible for the massacre of Haitians in October 1937 (estimates of the number slaughtered range between 10,000 and 20,000), his atrocity an echo of Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews. Trujillo wished to promote greater “Europeanism” and a kind of racial upgrading of his country as well as to rehabilitate his dismal international reputation. At the Évian Conference in July 1938, convened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss solutions to the Jewish refugee crisis, Hector Trujillo, the Generalissimo’s brother, extended a welcome to “as many as 100,000 political refugees.” Due to bureaucratic complications, only 500 families were able to benefit from the offer. (Indirectly, about 4,000 Jews received visas to enter the DR, enabling them to leave Europe for other destinations.)

Trujillo gave DORSA a 26,000-acre tract that once belonged to the United Fruit Company. However, DORSA, together with the JDC, insisted on paying Trujillo for the land. When the Jewish homesteaders discovered that only a relatively small area was suitable for agriculture, they developed cattle ranches. Within a few years, they built an export business for salami and sausages as well as a thriving dairy factory, all under the name Productos Sosúa. The company is still in existence today, but no longer manufactures meat products.

One reason for the settlers’ success can be attributed to Arthur “Don Arturo” Kirchheimer. He recognized that the island’s feeble pigs suffered from prolonged inbreeding. With the introduction of sturdier animals from neighboring islands, Kirchheimer rejuvenated the pig population, impressing the locals.

Rene Kirchheimer, born in Sosúa in 1942, is the only son of Arthur and his wife, Ilona. I meet him almost by accident on my second day in Sosúa, having followed the shaded path beside the beach in the direction of the place formerly called El Batey, where there is a synagogue and an adjacent museum. Bathed in sweat by the time I get there, I am discouraged to find the entrance gate locked, despite an “open” sign at the Museo Judío Sosúa.

A taxi driver shouts from across the street, warning me off the property. “Closed today!” he yells in English. Grateful for my Spanish, I explain that I am a writer looking for information about “los Judíos”; suddenly I am being led two blocks to the house of one of the few remaining Judíos—Rene Kirchheimer.

Kirchheimer is the son of an interfaith marriage (Ilona, a Lutheran, fled Germany with her husband). Deeply tanned with jet-black hair and bright green running shoes, he is a semiretired singer fluent in Spanish, German and English. Recalling his “wild” youth—pristine beaches and open countryside, school hours from 8 to 12 followed by playtime all afternoon—Kirchheimer says that as a 14-year-old he was sent to New York to live with his non-Jewish half-sister. “A reaction to the uncertainties of the Trujillo regime and my own rebelliousness,” he explains. He visited Sosúa each summer, coming back to resettle on the island a few times before returning permanently in 1991. With a grown son and daughter who both live in the United States, he is, for the second time, married to a Dominican woman.

With a few rare exceptions, most of the Jewish refugees-cum-pioneers departed from the DR within a few years of the end of the war. Among those who remained, some, as Trujillo hoped, married Dominicans; several who became disillusioned by homesteading or never wanted to be farmers moved to larger cities in the DR, such as Santo Domingo, then called Ciudad Trujillo. Once it became clear that nearly all of their extended families and friends in Europe had perished, the majority of the settlers left for the United States, where the cultural and socioeconomic environment felt more familiar. By the time Trujillo was assassinated in 1961, there were only about 150 Jews left in Sosúa.

On the grass in front of the synagogue, a stone plaque is dedicated to the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Jews in Sosúa, dated April 2015. I learn that there is to be a reunion of the Sosuaners, but it will commence two days after my departure. Meanwhile, Kirchheimer is eager to share his documents, photos and transcripts of interviews with his now-deceased father.

On my final day, with a plan to enter the museum at last, I find four Jewish women—all of them in their sixties and Sosúa-born—perched on the wooden steps of the synagogue. The women, who live in the United States, huddle in the shade, waiting for the caretaker to arrive and open its doors so they can prepare the synagogue for the reunion.

Two of them are sisters, Jeanette Cohnen and Eva Cohnen-Brown, who live in Miami and Anchorage, respectively. Once the synagogue is open, the group clean and air out the sanctuary and replace the blue velvet curtain covering the Ark with a richly embroidered white one that was donated for the 50th anniversary back in 1990.

In contrast to Kirchheimer’s enthusiasm, these women are reticent. “We are tired of interviews,” Jeanette Cohnen says, recalling news articles about the documentary that mentioned Sosúa. “Suddenly everyone is discovering us. And we’ve been misquoted.”

Near the conclusion of Tropical Zion, Wells writes that Sosúa’s postwar Jewish generation both do and do not identify comfortably within one cohesive community. They grew up speaking both the Spanish of their native country and the German of their parents’ countries, and had paler skin and higher status than many of their Dominican peers. Yet many of those who left for America still consider themselves Dominicanas. The Cohnen sisters, redheaded and freckled, express irritation when questioned about their ties to Sosúa. If someone says that they do not recognize that the Cohnen name is both Jewish and Dominican, says Eva Cohnen-Brown, “I tell them they don’t really know the history of this place.”

It is hard to say if Sosúa’s Jewish legacy will last another generation. The synagogue is well tended if underused; the pictures in the museum displays are fading on the walls.

There is not that much left for Jewish tourists to explore in this unusual experiment in Jewish pioneering. There is a street named after DORSA leader Dr. Joseph A. Rosen, but the gorgeous beach closest to El Batey now mostly hosts a resort. Down the street, you can see a burned-out building that once housed the original store for Productos Sosúa, and at one end of Sosúa Bay are ghostly vestiges of the United Fruit Company’s ramp to the sea.

Yet the city seal bears a Star of David. And at the Gregorio Luperón International Airport in Puerto Plata, I am astonished and touched to see that the departure lobby features several large photographs of Jewish settlers newly arriving in the DR, receiving a cool drink and a fresh banana. They are smiling and so very hopeful.

Elizabeth Rosner is working on a new novel called Survivor Café.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

alfred weinberg says

The whole thing started a few days after Kristalnacht on November 9th 1939. I was 2 years old and my brother was 8 years old.

The Weinberg family originated from a town called Emden from the northwest part of Germany. Our lives were comfortable, and we had a nice apartment,,. My father Jacob Weinberg was a bookkeeper working for a German company in the port of Emden. His father owned a tobacco store in the same town. When his father died, my father took over the store until he had to close it due to the Nazi’s rules. On November 10, 1938, the day after Crystal Night, My father left the house early in the morning to discard a gun that he owned from the store. As he was turning a corner, the Gestapo arrived at our house at about 5 o’clock that morning. My mother Emmy, his children Ernest and Alfred, and his father-in-law Nathan Van der Walde were woken up by the Gestapo and arrested. They were marched to a holding building where the other Jewish families were held. Ernest, who was 8 years old, was crying and was told by the Gestapo in charge to stop crying or he would shoot our mother. Meanwhile, my father was picked up by the Gestapo and marched to the same place where they were holding the rest of the town’s Jews. After several hours, the Jewish families were released and Jacob was taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

The next day, Nathan Van der Walde, his father-in-law who was a veteran from the German army, was able to find out where they had taken my father. After further investigation, he was told that they would release him if the whole family left the country. My mother had relatives in Holland, and she asked for help from them. She went to several agencies and was able to acquire the proper papers to be able to leave Germany. My father was released with the understanding that he and his family leave the country. When he was asked to talk about the concentration camp, he refused to talk about it. Our family was finally able to get the proper papers to leave the country. We were given a choice of Paraguay or the Dominican Republic. We chose the Dominican Republic. We left Germany to board a ship in Belgium. When we tried to cross Holland, We did not have a visa to cross Holland and we had to return to Germany. After arriving back in Germany, we had 3 weeks to leave or be arrested. We were able to book passage on a ship named Klaus Horn to the Dominican Republic.

We family arrived in Ciudad Trujillo on March 1939.

Libby Barnea says

I’m happy to post your comment if you cut it down to under 200 words or so. Thanks.

Kitty Loewy says

Alfred Weinberg my father also

Lived in Sosua for several years. I am seeking others with similar backgrounds.

Kdloewy@ gmail.com

June Hersh says

I would love to connect with anyone who has recollections of Sosua, please email me at junehersh@gmail.com

Giselle Trujillo says

Thank you for sharing your valuable memories. My great uncles was President Trujillo and I am so happy he opened the doors to save lives, when 31 other nations would not.

– Giselle Trujillo

June Hersh says

I would love to hear more for a book I am writing about Sosua. Please email me at junehersh@gmail.com

A J Sidransky says

You might want to read my debut novel Forgiving Maximo Rothman which is set in Sosua. It was selected by National Jewish Book Awards as a finalist for best debut novel in 2013. I would have loved to speak with you about Sosua for your article. My aunt and uncle were among the settlers.

Beverly Pottern Shapiro says

In 1976, my husband, Mel, and I happened upon Sosua. At that time I was a candidate for a graduate degree from Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles abd chose Sosua as the topic. We returned in April 1977 to tape and photograph the Jewish settlers remaining there. Some of my photos have been published; some are in he Archives at Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati. Except for an article I wrote for the North Shore Jewish Newspaper when I returned to Marblehead, Ma, none of my material has been published. One of the most interesting stories involves a stranger at the Passover Seder. Other stories are about the people, the politics and crime, and the vision of the Future of Sosua.

I am very willing to share my research.

Ironically, when we retired to Longboat Key, FL, our next door neighbor was Greta Brooks, widow of Dr. John Brooks, the doctor in Sosua, who had retired next door to us. Together, Greta and I spoke to the condo association comparing Sosua then, Greta, and now, my research. Quite amusing…..

Beverly Pottern Shapiro says

Your article is the very best, most concise review of Sosua then and now. Not having returned since 1977, I would be most interested in comparing findings. I am sure most of those I interviewed are no longer living in Sosua. Their stories might be of interest to you. Yours would certainly be appreciated. It was one of our greatest adventures.

Beverly P Shapiro

Elizabeth says

Dear Beverly, Are you still available to connect about your interviews and stories? I’d like to know more.

Elizabeth@ElizabethRosner.com

Thank you.

Rene J. Kirchheimer says

Hello, enjoyed reading the article Elizabeth. I’m stll here in Sosua, yourself or anyone else coming down , I’ll be glad to talk to you about our history.

June Hersh says

Rene, I would love to connect, please email me at junehersh@gmail.com

Renée-Chaja says

Dear René,

I am going to stay in Puerto Plata September 10th to September 24th and would be very happy to meet up. I am a German jew from Berlin and would be happy to know more about Sosuas history and people. I would be very happy if you could write me rroeske@hotmail.com.

Bunny says

Hi Rene, we are 2 Israeli women going on a vacation to SD and would love to visit Sosua. My email is bunnyAlex@msn.com.

Rene J. Kirchheimer says

Renee-Chaja; sorry just saw your comment today 12/20/2016.

patricia says

Beautifully written article. You are indeed a writer.

While it is impossible to explain why affinity tied me to Jewish culture I will say that I was a young girl

when the match was struck. As an old woman that match lit a fire that still burns.

I am not Jewish which never mattered to me. Cultural appropriation was never the issue.

It is what it is. I know what I feel. What I have always felt and throughout my long life my path continually reintroduces me to that fire. Thank you for your article.

Larry says

I have been researching all things Trujillo for two years now, and I can’t help but to ask, just where does this notion of Trujillo accepting Jews to settle into DR to “whiten” the Dominicans or as an attempt to put behind the 1937 Haitian-Dominican border incident comes from? Where is the source that can be considered undisputable proof that these were Trujillo’s intention other than the same anti-Trujillo narratives that have been created since his assassination?

I’ve read hundredths of documents from the Jewish archives and letters from Dr. Rosenberg and other settlers, including several letters and memos from Trujillo to DORSA and not one single document indicates nor says anything close to Trujillo doing this humanitarian act to “whiten” the Dominican race, nor to cover the 1937 Haitian-Dominican incident which has also been manipulated by liberal or anti-Dominican historians to appear like a race-related event, which isn’t so.

I encourage all to read this fact based article where the Jews of Sosua gave Trujillo an award in the late 50’s for his “humanitarian” act. http://trujillodeclassified.com/2016/12/14/speech-of-jew-refugees-in-sosua-praising-trujillo-for-saving-them-from-hitlers-persecution-and-building-them-a-synagogue/

and this one which has documents regarding the 1937 border conflict that’s frequently used to claim that Trujillo ordered a massacre of Haitians due to his hatred of Haitians. http://trujillodeclassified.com/2016/04/30/1937-dominican-haitian-border-killings-border-clashes-and-invasions-of-dominican-territory/

Regards,

Larry

Frank Kohn says

My mother and father met in Sosua and my mother now sist at the survivor

s desk at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and speaks with visitors about her experience in Berlin prior to leaving in late 1941 (my dad fled Austria and arrived in Sosua in 1940–he was one of the physicians at the clinic you menitons). I’.m sure my mom would be happy to speak with you if you like.

Lisa Arm says

My grandparents also met there – Fritz and Trude Arm. I recognize the Kohn last name. Alfred Weinberg – I’m so glad you shared that story. People seem to forget that there was a reason our families all landed in Sosua. Thank you Elisabeth Rosner. We must never forget and the Sosua legacy will live on. Kitty Loewy I will send you an email although your post was 3 years ago.

William Lewis Wexler, Esq. says

Trujillo took our people in while FDR sent them back to Germany to die. Many, but not my father (o’h), venerate FDR without realizing that unlike him the Latino countries saved so many.

Elizabeth Rosner says

I want to offer a very belated note of thanks to all of you who shared your thoughts and memories in response to my article. It’s clear there are many more Sosua stories to be collected, and I’m happy to hear from anyone interested in contacting me directly. I can be reached via my website’s email address, which is elizabeth@elizabethrosner.com.