Arts

Exhibit

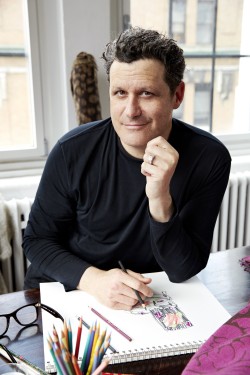

Isaac Mizrahi: Man on the Runway

Interesting clothes, says artist, fashion designer and entrepreneur Isaac Mizrahi, “are those that look slightly mistaken, or very, very surprising.”

That irreverent and inventive spirit informs a new show “Isaac Mizrahi: An Unruly History”—the first museum exhibit of Mizrahi’s work—at New York’s Jewish Museum. The exhibit, which runs from March 18 to August 7, weaves together the threads of Mizrahi’s three-decade career spanning fashion, film, television and the performing arts. Among the 42 “looks” and 10 costumes on display are clothing, hats, jewelry and shoes as well as the designer’s drawings.

Mizrahi’s fresh designs and exuberant showmanship electrified the fashion world when he burst onto the scene in the late 1980s and redefined what it meant to be an American fashion designer, says guest curator Chee Pearlman. “His iconoclastic mash-up of high and low radically reassessed codified norms of beauty,” she writes in the catalog, the first publication devoted to Mizrahi’s work. His “groundbreaking preoccupations with color, print, gesture and surface,” she adds, “place his work in the avant-garde of modern design.” Mizrahi has dressed politicians and actors including Hillary Clinton, Michelle Obama, Meryl Streep, Sarah Jessica Parker, Sandra Bernhardt and Natalie Portman (a cochair of Friends of Isaac, which provided financial support for the exhibition). But, Mizrahi emphasizes in an interview in the catalog, “I always had real women in mind, not fantasies.” He reaches those women through venues such as his weekly QVC show, Isaac Mizrahi Live!

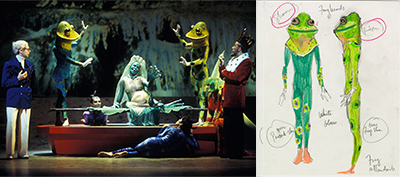

Though Mizrahi is best known for fashion, he has also directed and narrated a children’s production of Peter and the Wolf at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York; directed and designed The Magic Flute and A Little Night Music for the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis; and won an Audience Award at the 1995 Sundance Film Festival with director Douglas Keeve for Unzipped, a documentary about the making of his fall 1994 collection. He appears as a judge on the television series Project Runway: All Stars and is currently at work on another series and memoir.

The exhibit opens with a wall of fabric swatches arranged by color, chosen from the hundreds in Mizrahi’s personal collection. “It’s like seeing all of Matisse’s paintbrushes,” says Pearlman. Mizrahi’s fearlessness around color allows him to experiment with bold palettes that translate into creations, on display, like the Blossom Blazer, a silk jacket with a ruffled collar produced in hot pink, orange and aquamarine.

Color is emotional, fun and the “biggest luxury there is,” Mizrahi says. “Every color has a color in it that makes me crazy,” he adds in an interview at his New York apartment. “There’s a shade of blue; there’s a shade of orange that makes me insane. There’s a shade of green that makes me want to kill myself with happiness.”

In fact, he established his reputation partly through the audacious use of color during his first runway show in 1988. Mizrahi sent out models dressed in shades of gray, camel and brown until, suddenly, supermodel Linda Evangelista walked out in a giant, hot-orange overcoat, a bright-yellow jumpsuit, a red scarf and purple Manolo Blahnik desert boots. The audience went crazy. The semi-couture Orange-Orange Coat and Striped Jumpsuit as well as Mizrahi’s sketches are displayed in the exhibit.

Bold graphics in other designs are often inspired by the works of artists and photographers. Matisse’s costumes for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes spurred Mizrahi’s collaboration with Israeli-born artist, friend and neighbor Maira Kalman. She created a black-and-white series—stripes, checks, harlequins, swirls and dots of different sizes—that Mizrahi imprinted on linen jackets, satin smocks and diaphanous gowns. For the Exploded Tulip and Exploded Rose ready-to-wear dresses, Mizrahi commissioned photographs in the style of photographer Irving Penn and printed them on silk crepe dresses, wool trousers and jackets.

To allow the designs to pop, the rooms in the exhibition are quiet, white-walled spaces encircled by white scrims. In a not-so-veiled reference to Unzipped, the scrims pay homage to Mizrahi’s daring decision that allowed the audience to see the models changing through a gauze curtain in the 1994 show.

The mannequins, posed formally on platforms in the center of the rooms, are draped with ready-to-wear from the Isaac Mizrahi New York label (1987 to 1998), the semi-couture collections (2003 to 2011) and the Target line (2002 to 2008). The pieces represent Mizrahi’s signature sensibilities as well as iconic moments from his career, framed by a flair for the theatrical. He titles every collection, and each look has its own storyline. That dramatic streak dates back to his childhood, when he created puppet shows in his parents’ garage—writing, directing and performing as well as building and costuming the puppets.

A key part of Mizrahi’s toolbox is his mastery of cultural, historical and political concepts, which he reinvents through design. Totem Pole—worn by supermodel Naomi Campbell when she was featured on a 1991 cover of Time magazine—riffs on Native American iconography. Masks of mouths and eyes are embroidered on a form-fitting gold-flannel gown, and long braids playfully wind down the back of the dress so the wearer herself becomes totemic.

Some of Mizrahi’s looks in the exhibit are just plain fun, simultaneously affirming his conviction that clothes don’t have to be uncomfortable to be elegant. In Extreme Kilt, he creates a tartan plaid cashmere strapless gown inspired by traditional kilts (a sketch is on display). Sack Pants, a ready-to-wear big rectangular canvas sack with legs and cinched with a belt, fits any body type (he originally invented them for himself). Anything can inspire Mizrahi—even elevator padding, which he turns into a quilted gown in a patchwork of blue, green, gray and silver silk, with a bodice molded from grosgrain ribbon (Elevator Pad Gown, semi-couture). His humor sets him apart from other designers: In a 2009 runway show he called Smile, he topped a jacket with a leather hat shaped like a tote bag, borrowing from images of African women carrying baskets on their heads.

“Isaac cannot be put into a silo or a box,” Pearlman says, explaining the exhibit’s title. “He doesn’t have only one direction or career. There is an unruly freedom to his activities: the freedom to direct a Mozart opera by day and sell his cheerful mass-market line live on QVC at night.”

“The word ‘unruly’ speaks more to who I am rather than to what my clothes are,” says Mizrahi, who participated fully in shaping the exhibit. “My clothes are sophisticated and subtle and funny. They are ‘ruly,’ but I am unruly and my history is slightly unruly. I take clothes seriously. I take women seriously, I take feminism seriously, but I don’t really take fashion seriously. Maybe that’s why I am good at it. I don’t play by those rules. I’m Un-rule-y.”

Mizrahi’s jewish identity is integral to his wide-ranging work, says Jewish Museum Director Claudia Gould. Born to a Syrian Jewish family in Brooklyn, New York, Mizrahi, 54, attended Yeshivah of Flatbush before transferring to the High School of Performing Arts. After graduating from Parsons School of Design, he worked in the studios of Perry Ellis, Jeffrey Banks and Calvin Klein and launched his own label at the age of 27.

His father, Zeke, a children’s clothing manufacturer, gave him his first sewing machine at the age of 10, and Mizrahi says he derived much of his sense of style from his mother, Sarah. “When I was growing up, the idea of being truly stylish was more akin to scavenging, reinventing, than it was to luxury and spending loads of money,” he says.

There are only a few overt nods to his Jewish background in his designs: a suede-and-brass Star of David Belt and Tee Pee Shearling, which fuses Jewish and Native American motifs beaded onto suede shearling coats and cocktail dresses, accessorized with layers of gold chains with Star of David medallions. The designs, on display in the exhibit, were part of a 1991 show called Pow Wow Dressing and a group of looks titled Tee Pee Town, a tongue-in-cheek yet respectful reimagining of a roadside tourist shop filled with Native American tchochkes and souvenirs, presented in a couture context. “At that time, America was defining itself as a fashion capital, so any American reference I could call into play, I did,” explains Mizrahi.

“I talk a lot about being funny, being whimsical, but it’s also about elegance, which is just as important to me,” says Mizrahi. Colorfield, a semi-couture hand-painted, forest-green linen canvas coat with Baccarat crystal buttons engraved with Mizrahi’s name, resembles a piece of art. Part of his 2004 High/Low collection, he paired it on the runway with Target capri jeans. He even combines high and low behind the scenes: To produce The Real Thing, a shimmering, ready-to-wear red shift crafted from Coca-Cola cans cut into paillettes (giant sequins) for his spring 1994 runway show, he worked with We Can, a New York charity. It employed ex-convicts and homeless people to gather and flatten empty Coca-Cola cans. After a luxury sequin-maker in Paris cut the aluminum into paillettes, they were sent to India to be hand-embroidered onto silk.

“Coke is the icon of American capitalism,” assistant curator Kelly Taxter writes in a catalog essay. Like Andy Warhol’s painting of a Coca-Cola bottle, Mizrahi, too, explored a “democratized idea of luxury—a very rich and a very poor person could enjoy the same, perfectly executed product.”

Mizrahi backed his democratic spirit with a practical leap. After he closed his company in 1998 due to financial difficulties, he embraced the mass market with a landmark deal with Target and, later, a license for clothing, accessories and home décor for Xcel Brands, which now owns and manages Isaac Mizrahi New York. Through Xcel, he has just entered into a partnership with Hudson’s Bay and Lord & Taylor.

Mizrahi’s creations for theater and dance fill a Costume Room in the exhibit. Beginning in the 1990s, he designed costumes for Twyla Tharp and Mark Morris, a close friend, choreographer and creative ally. The show includes selections from performances of the Mark Morris Dance Group—Beaux (San Francisco Ballet); Magic Flute; Peter and the Wolf; and The Women (Roundabout Theater), which earned him a Drama Desk award. Excerpts from the performances are shown on a video monitor.

In another room, a specially produced multiscreen video installation highlights Mizrahi’s role as a performer. Viewers can watch clips from runway shows; Unzipped; The Isaac Mizrahi Show (a television show); Project Runway; Isaac Mizrahi Live!; LES MIZrahi, a cabaret show; and numerous film and television cameos, including Sex and the City and three Woody Allen movies.

Mizrahi continues to design. He created five new coats that will be unveiled with the exhibit’s opening. “I think what got me where I am is my taste for new things,” he says. “To be easily bored is probably a prerequisite for any good fashion designer.” The show allowed him to reflect on his wide-ranging interests—a luxury his extraordinary pace doesn’t usually afford. “The making of this show,” he concludes, “has made me more of an artist.”

Rahel Musleah’s website is rahelsjewishindia.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply