Arts

Personality

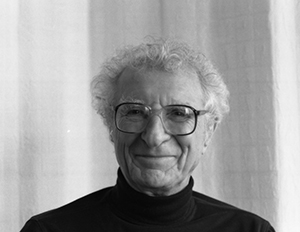

Sheldon Harnick

Sheldon Harnick closes his eyes, gestures widely with his arms and, at age 91, delivers every lyric of Merry Little Minuet correctly and in tune.“They’re rioting in Africa/There’s strife in Iran,” he sings in his still-resonant baritone. “What nature doesn’t do to us will be done by our fellow man.” He punctuates the litany of terrible events—almost as relevant as when he wrote the song 62 years ago—with a series of jaunty whistles.

Harnick’s innately cheerful attitude befits the man who, with composer Jerry Bock, gave voice to the soul of Tevye the milkman through timeless poetry and music. This year, as Fiddler on the Roof celebrates its 50th anniversary with its fifth Broadway revival, Harnick’s lyrics seem enduringly apt: “God would like us to be joyful even when our hearts lie panting on the floor. How much more can we be joyful, when there’s really something to be joyful for? To life! To life! L’chaim….”

In addition to Fiddler, Harnick has written the lyrics to a dozen musicals, including The Rothschilds (an Off-Broadway revision, Rothschild & Sons, was staged last year); She Loves Me (a Broadway revival opens in March); and Fiorello (based on the life of crusading New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia). The theater world has recognized his talent with a plethora of awards, arrayed unpretentiously in a corner of his New York apartment, including a Pulitzer Prize, three Tony Awards, two Grammy Awards, two New York Drama Critics Circle Awards, three gold records and a platinum record. He points them out matter-of-factly upon request, admitting that “I guess, way deep inside there’s a feeling of pride.”

A principled defender of his work, he made sure that 10 bars of music that had been added to the instrumental opening (“Tradition”) in the new revival were removed. “The show should be done as we wrote it,” says Harnick, natty in a navy jacket, gray pants and a plaid shirt, his plentiful white hair curling gently. The oversized glasses that dominate an Al Hirschfeld caricature of Harnick (it hangs in the foyer) have morphed from black to light brown today.

Fiddler, says Harnick, gave him and his Jewish cocreators (Bock; book writer Joseph Stein; director Jerome Robbins; producer Harold Prince) an opportunity to reconstruct the shtetl world that had been exterminated and “to show non-Jews that there was nothing to be afraid of in Jews, nothing to be jealous of in Jews. They were ordinary people who suffered, as ordinary people do, human beings who wanted to live simple lives and enjoy themselves.”

The show also afforded him the chance to explore his own background: He grew up Orthodox in a non-Jewish Chicago neighborhood and frequently experienced humiliating verbal and physical anti-Semitic attacks that led to a self-consciousness about being Jewish, doubled by the specter of Hitler. “In grammar school,” he recalls, “I was embarrassed for another Jewish boy who came from the Old Country and still had an accent. The teacher made fun of him. I’m embarrassed now by my own embarrassment.” But, he adds, he idolized his childhood rabbi so much that for a while he, too, wanted to become a rabbi, even playing Mattathias in a synagogue theatrical.

On a very personal note, he recounts that “Do You Love Me?” grew out of a subconscious wish that his parents could have related to each other as tenderly as Tevye and Golde (lack of money during the Depression caused bitter fights). He wept when he saw the song performed early on. His own relationship with his wife of 50 years, Margery, an actress, artist and photographer whom he met on the sets of Tenderloin and Fiorello, is far different. He doesn’t miss a chance to articulate his love for her. The marriage is the second for Margery and third for Harnick: He married his childhood sweetheart and then briefly wed comedian/actress Elaine May.

“Sheldon is honest and direct and has an adorable sense of humor. That’s the way his lyrics are,” says Margery Gray Harnick. Their wedding album is a Who’s Who of theater, from composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, whom Harnick calls his hero, to actor Jack Cassidy. Recently, the Harnicks collaborated on a book entitled The Outdoor Museum: Not Your Usual Images of New York (Beaufort Books), featuring her photography and his poetry.

Not much has changed in the apartment overlooking Central Park West that they moved into as newlyweds, including the original white stove. “I love this apartment,” he says. “Why? My wife lives here.” He makes sure to clarify the unusual spelling of her name and then spells out Sheldon: Shin, lamed, daled, nun. His Hebrew name is Shalom. “Fitting isn’t it?” Margery comments. “Yes, peace,” he replies, adding that it is especially meaningful in light of his connection to the Sholom Aleichem stories on which Fiddler is based.

How does Harnick’s Jewish identity express itself today? “I like pickles,” he says, joking, his impeccable timing worthy of a standup comic. He chuckles delightedly at his own one-liners but turns serious, noting that he is a “loyal Jew” and that Judaism drives his heightened social consciousness and care for minorities. He belongs to the American and New York Civil Liberties Unions and to Congregation Rodeph Sholom in New York. His lyrics always serve the characters, yet sometimes they also reflect his commitment to justice. In The Rothschilds, which focuses on the banking family that rose to international achievement, Nathan and Jacob Rothschild sing: “In my own lifetime I know the dangers that we’ll face” (as Jews, Harnick clarifies). “In my own lifetime I’ll do my best to make the world a safer place.”

How does Harnick’s Jewish identity express itself today? “I like pickles,” he says, joking, his impeccable timing worthy of a standup comic. He chuckles delightedly at his own one-liners but turns serious, noting that he is a “loyal Jew” and that Judaism drives his heightened social consciousness and care for minorities. He belongs to the American and New York Civil Liberties Unions and to Congregation Rodeph Sholom in New York. His lyrics always serve the characters, yet sometimes they also reflect his commitment to justice. In The Rothschilds, which focuses on the banking family that rose to international achievement, Nathan and Jacob Rothschild sing: “In my own lifetime I know the dangers that we’ll face” (as Jews, Harnick clarifies). “In my own lifetime I’ll do my best to make the world a safer place.”

Harnick and his cocreators worked hard to buttress Fiddler’s Jewish themes with universal appeal.He recalls actress Florence Henderson exclaiming, “‘Sheldon! This is about my Irish grandmother!’ And I thought, ‘That’s exactly what we wanted to accomplish.’”

Alexandra Silber, 32, who plays Tzeitel, the oldest daughter, in the current revival and played Hodel, the second oldest daughter, in a 2007 London revival, says that “anyone who has loved, been part of a family, faced generational challenges or been oppressed can relate to the timeless themes. Fiddler captures the human ability to endure. The characters refuse to indulge in self-pity. Their spirit cannot be broken.” As Tzeitel, she says, singing the lyrics “brings out the determination to activate agency in my own life.”

Silber, who counts Harnick as a mentor, a friend and a surrogate grandparent, says Harnick’s sharp mind is complemented by “a beautiful softness—he’s appropriately sentimental.” She adds that his lyrics articulate Judaism’s perspective on adversity as well as his feelings about being in love and quotes a favorite line from She Loves Me: “My teeth ache from the urge to touch her.” The musical was based on the 1940 film, The Shop Around the Corner, updated again as the 1998 romantic comedy, You’ve Got Mail.

Harnick is an expert musician, an intrepid singer who still takes voice lessons and a fiddler in his own right. He played the violin until a year ago when he injured his shoulder and composes on a keyboard in the living room. “I’ve always loved music, especially classical music,” he says. “That’s a gift from God.” Sensitive, philosophical and a self-admitted worrier, Harnick credits the combination of Bock’s buoyancy with his own “lack of confidence” as the right mix for the rich songs they produced.

Bock and Harnick had a special way of working: Bock would record up to a dozen melodies at a time and would send them to Harnick, who would be excited by two or three and set them to lyrics. If he was stuck, he would often walk to break writer’s block. “Once I was singing a melody to myself and was walking across the street when suddenly I heard this loud honk,” he recalls. “The truck driver said, ‘You almost got yourself killed!’ I said, ‘It’s O.K.! I got the lyric!’” The 14-year Bock-Harnick collaboration ended in a dispute in 1970 during the writing of The Rothschilds; they eventually re-established their personal relationship.

“Sheldon creates art. And though his facility for lyrics is unsurpassed, he never draws attention to himself by making a rhyme or an allusion a tribute to his own talent,” write Bill Rudman and Ken Bloom in the accompanying booklet to the audio collection Sheldon Harnick: Hidden Treasures, 1949-2013. Some are pieces cut from Broadway shows, like “We’ve Never Missed a Sabbath Yet,” the original opening for Fiddler that was replaced with “Tradition.” Harnick explains the genesis of the change: At weekly meetings for Fiddler, Robbins would ask, “What is this show about?” “We realized it was about the changing of tradition, exemplified by the romances of Tevye’s daughters. He instructed us to write a song explaining what these traditions were.”

Tributes to Fiddler abound in the apartment, from a show poster in the hallway to a shofar that was originally a gift from Harnick to Robbins. Harnick was able to retrieve it after Robbins’s death. Among Harnick’s prized possessions are a signed card by lyricist Yip Harburg (Wizard of Oz; Finian’s Rainbow) who encouraged his talent; a small bronze Rodin replica of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky; and photographs of his family: daughter Beth Dorn, who lives in California, and son Matt, a scientist and photographer who takes care of their second home in Easthampton, New York. Harnick’s sister, Gloria Parloff, is a retired editor who lives in Teaneck, New Jersey. His brother, Jay, an actor, singer and founder of a children’s theater, died six years ago.

Harnick writes in pencil or ballpoint pen in a black leather easy chair in his office, studying the plot and characters and reading source materials to put himself in the character’s shoes. The songs help move the story forward. “I look for a moment in a scene where a character says something moving or funny,” he says. “That’s where the song will be.” The rhyme comes later. “The audience has to grab that lyric the first time they hear it. The trick is to be both fresh in the language but also immediately comprehensible. I try to be very strict with myself because I want my work to compare with that of other people I admire most, going back to Gilbert and Sullivan.”

He discovered early he had a talent for poetry and music, influenced by his mother, Esther, who used to celebrate every occasion with an original poem. Many members of her family played piano, violin and sang. Harnick’s father, Harry, a dentist, was born in Austria-Hungary and came to America at the age of 15 to look, unsuccessfully, for his father: he had emigrated earlier and promised to send for his family, but never did. By high school, Harnick was acting and writing songs, a talent he continued to develop in the Army. He earned a bachelor of music degree from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, majoring in violin. When a college friend, singer and actress Charlotte Rae, came back from New York with an LP of Finian’s Rainbow, Harnick was hooked. “I heard Yip Harburg’s lyrics and I thought, ‘That’s what I want to try to do.’”

Harnick moved to New York in 1950 and began submitting songs for musical revues—a form less complex than writing for musicals. With Rae’s help, he met and auditioned for Harburg. On Harburg’s advice, he wrote character and comic songs and, in fact, humor helped establish his reputation. His first song for a Broadway show was the hilarious “Boston Beguine,” sung by Alice Ghostley. In addition to Bock, he worked with composers including Richard Rodgers, Joe Raposo and Michel Legrand. He later expanded his talents to translating operas and writing librettos.

He has succumbed just a little to age, apologizing for some loss of hearing and memory while in the very next breath reciting a poem he wrote in fourth grade. He remains busy as ever, revising a short opera about Lady Bird Johnson with composer Henry Mollicone and still casting his votes for the Tony Awards. His caricature was just unveiled at Sardi’s, a well-known theater hangout and the birthplace of the award. And he is eager to fulfill an unfinished dream—a musical for which he is even contemplating writing the book. “I’m not going to mention what it’s about—or people will steal it,” he says, smiling.

What would Tevye think of the world today? “He would think it’s bad for the Jews,” Harnick replies, then pauses. “What he’d be thinking is, ‘Wherever my daughters are—I hope they are all right.’”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Elissa Smiley says

Thank you for featuring this exceptionally talented and wonderful man

My Dad, Charles Jaffe, had the privilege of being Musical Director of Fiddler on the Roof from 1964-1972

Nade Peters says

A sentence early in this interview says that Harnick “married his childhood sweetheart.” Can you tell me who this was, because my recollection is that his first marriage was to Mary Boatner, a fellow student at Northwestern University, and not a childhood friend.