American View

Life + Style

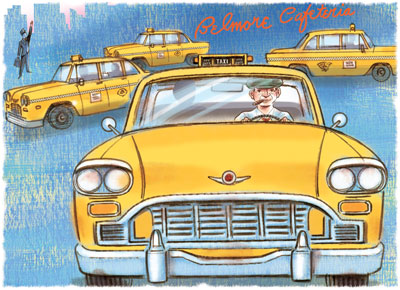

A Fare to Remember

Today, if you hail a taxicab in New York, the driver will likely be an immigrant from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Ghana, Greece or Haiti. Often, you can tell their origins not only from their identification signs but from the music they play on their radio—calypso, French African or Egyptian—or their conversations on earpieces in their native language.

Some wear the turbans that mark them as Sikhs, others have Islamic prayer beads dangling over their dashboards.

From the early 20th century through the 1970s, the image of the New York cabdriver was that of a first-generation American. He—the driver was usually a man—spoke in a “Noo Yawk” accent, smoked a cigar or cigarette and gave opinions on everything from sports to politics. And, often, he was Jewish. Indeed, there were so many Jewish drivers that it was difficult to get a cab on Rosh Hashana or Yom Kippur. In 1920, the Jewish Daily Forward estimated that 20,000 of the city’s 35,000 drivers were Jewish.

So when the media portrayed New York cabdrivers, they were often Jews. In the 1932 film Taxi!, James Cagney breaks into fluent Yiddish to give directions to a Yiddish-speaking man trying to get to Ellis Island; Cagney, an Irish American, learned Yiddish growing up on the streets of Yorkville, a neighborhood of New York. In Woody Allen’s 1976 McCarthy-era film The Front, Zero Mostel’s character has a television show in which he plays “Hecky the Hackie,” who knows “a million stories.” As late as 1987, the movie Sweet Lorraine, about the last days of a fading Catskills resort, shows comedian Freddie Roman entertaining a convention of the Greater Metropolitan Society of Kosher Cabbies.

What attracted Jews to the industry? For starters, all you needed was a license—and there was no competition from private cars that are summoned by phone call (that service dates to the 1960s), Uber or city-licensed green cabs for the outer boroughs (introduced in 2013). Before the dramatic rise in crime of the late 1960s and through the 1980s, yellow medallion cabs went everywhere in the five boroughs. The classic Checker cab, used from the 1950s through the early 1980s, was so roomy it also had two foldout metal seats on the floor that could be used if need be.

(On the other hand, today’s New York drivers and passengers will soon enjoy the new Taxis of Tomorrow being unrolled—they will include USB chargers, greater legroom, sliding doors to keep cyclists from getting hit, a panoramic roof for great views and yellow seat belt straps to make them easier to find on black seats.)

In 1937, says Alan Fromberg, Taxi & Limousine Commission spokesman, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia set up the medallion system of cab ownership; as of September 2015, there were 13,587 licensed taxis on the road.

Some of the early Jewish cabbies used taxi driving as a stepping-stone; for others it was a lifelong job. “You hear about the [taxi drivers] who went [on] to college, but that’s not the whole story—there were others who didn’t,” says William B. Helmreich, professor of sociology and Judaic studies at City College and City University of New York Graduate Center and a onetime cabbie. “You kept 47 percent of your fares as income, and the rest [of your income] was from tips. Jews…are a garrulous lot, and this worked to their advantage in getting tips.”

In addition to the regular drivers, Helmreich says, “you had the hack[s], who took people to the Catskills in the summer, you had the limo drivers and you had the summer drivers,” usually young people and college students. “I was a summer driver as a graduate student in 1969. The summer drivers survived into the 1970s, but not the 1980s.”

Al Miller grew up in Brownsville, then one of Brooklyn’s poorest Jewish neighborhoods. “My father was born in 1917 and went to Thomas Jefferson High School, but dropped out because of the Depression around the 11th grade [to help support his family],” Bertram Miller says. “He worked in a defense plant during World War II, but had few skills. He purchased a yellow cab and a medallion, which cost little at the time, but sold the cab sometime in the 1950s because he found the upkeep so expensive. After that, he worked for the Ackerman cab fleet in Brooklyn.”

Miller recalls that the long hours away from his family and the rising crime rate were among the reasons that, in 1966, his father became a subway motorman.

Danger was part of the job from the beginning, but escalating street crime in the late 1960s and 1970s hastened the exodus of Jews (and Italians) from the industry. Miller was held up several times, once at knifepoint. Helmreich, too, remembers the time several men tried to grab the lockbox on the floor of his cab through his open window before speeding away. In response to the rising dangers of the job, the Taxi & Limousine Commission mandated bulletproof dividers separating the driver from the back seat in 1967 for anyone driving at night, then required them for all cabs in 1971.

But the job also came with a lot of fun, kibitzing and tall tales. In Confessions of a New York City Taxi Driver (The Friday Project), cabbie-author Eugene Salomon, a Yankees fan, recalls how in the early 1980s he asked his fare, Paul Simon, if the singer could buy the team.

“Are you crazy?” Simon replied. “I don’t have that kind of money. You should ask McCartney.”

Another time, he picked up two men: One well-dressed, the other disheveled and ranting a mile a minute. At the end of the ride, the well-dressed man turned to Salomon and said, “That’s Abbie Hoffman. I’m his parole officer.”

Between fares, taxi drivers would hang out—usually in cafeterias—and play pinochle, gin rummy and poker. The best-known hangout was the Belmore Cafeteria on 28th Street and Park Avenue South. It served East European Jewish-style foods—borscht, brisket and noodles and cheese and had a free seltzer dispenser. It was immortalized in Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver. Other popular hangouts were Katz’s Deli at Houston and Ludlow Streets, Leo’s on East 86th Street and the Horn & Hardart at 57th Street and Seventh Avenue.

According to Bertram Miller, George’s Diner on Coney Island Avenue and Cortelyou Road in Brooklyn was for drivers getting off the Prospect Expressway.

Jews were also at the forefront of union organizing. In a 2006 obituary in the Village Voice, writer Tom Robbins recalled that Leo Lazarus, a World War II veteran and well-known labor activist, would often shmooze with his passengers and break out into old songs like “It Had To Be You.” Lazarus, Robbins wrote, was at heart a lefty who saw the world as divided into workers and bosses. Even in his eighties, Lazarus, who once ran for president of the now-defunct Taxi Drivers Union, was constantly “talking union” with other drivers and speaking out at meetings.

As late as the 1970s, taxi driving still attracted a few adventurous young Jews. Edith Linn, who today teaches criminal justice at Berkeley College in New York, started work as a driver after graduating from the State University of New York at Binghamton.

“I came from Long Island, and when I moved to the city, I felt the best way to get to know the city was as a cabdriver,” she says. “I didn’t know any other Jewish drivers. If I [had], I probably would have gravitated toward them. But that may have been because I was driving out of a garage in the Bronx. Actually, I was considered more unusual because I was a female driver.”

Like others, she had brushes with danger. Once stuck in a traffic jam, she used the time to count her money; a teenager tried to put his hand through the open window and snatch the bills. Linn grabbed his arm and a struggle ensued. She quit driving soon after, joined the New York Police Department and became religiously observant.

Just as Jewish drivers were aging out of the industry, there began—in the 1970s and skyrocketing in the 1980s—a wave of Jewish cabbies, immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Many had been professionals in their native country but were forced into taxi driving because of their poor English skills. While some drove for private car services—considered safer because drivers only picked up prearranged fares—others drove yellow cabs.

Gina Osnovich’s father, the late Michael Osnovich, came to the United States with her family in 1980 when she was 2 years old. A former musician, her father was steered to driving a taxi by word of mouth soon after he arrived. “We were in an immigrant hotel and the first thing [he needed] to do was to get a job,” Osnovich recalls. Osnovich drove until 2012, when diabetes forced him to retire. He was part of an informal group of friends—all Russian immigrant cabbies.

“Sometimes, he and his fellow drivers would hang out at Kennedy Airport, where they would play cards,” Gina Osnovich says.

Her father was robbed several times, and his daughter believes that the job enabled “bad habits” like heavy smoking. “If you work in an office, you have to take a break and go outside to smoke, but with a cab, you have a break [after each fare],” she says.

The world of the Russian Jewish cabdrivers of the 1970s and 1980s is poignantly and humorously captured in Vladimir Lobas’s Taxi From Hell: Confessions of a Russian Hack (Soho Press). In it, Lobas describes how drivers constantly jockey to pick up “a Kennedy,” their nickname for a wealthy passenger who might be a big tipper. An Albanian driver once be–rated Lobas for picking up a fare on a Midtown side street rather than staying in front of a nearby hotel, where he might catch “a Kennedy.” Lobas’s own nickname? “Bagel.”

Today, there are fewer Russian Jewish cabdrivers. From the beginning, many were working toward buying their own cab and renting it to others. While new immigrants are still coming from Russia and Ukraine, Osnovich says that “many now stay with relatives…and go to school. They often already learned English in Russia.” Some have high-tech skills.

Seth Goldman, 54, who started driving in 1984, is the rare veteran Jewish driver. “I wasn’t doing well in college, I was still living at home and I needed to get on my feet, so I got a hack license,” he explains. Later, he went back to college, graduated and worked as an English teacher in junior high school. Discouraged by conditions in the classroom and a lack of support from the school system, he returned to his cab.

“I’ve driven out of the same garage [in Queens] since the 1980s, and I can’t remember seeing one other Jewish driver there,” he says. Still, “if you go to a Russian neighborhood and call for a car, chances are you’ll get a Russian driver, who may or may not be Jewish.”

When the Belmore closed in 1981, driver Marvin Brenner told Dorthy Gaiter of The New York Times: “We’ve all got degrees in cabology. That makes you a philosopher, psychologist [and] gourmet cook.”

The old-time Jewish cabdrivers made customers’ rides less tedious and, in the end, enriched the quality of life for everybody.

Raanan Geberer is a journalist in New York.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply