Being Jewish

Commentary

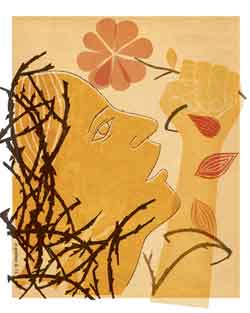

Finding Freedom Within Ourselves: Righteous Women in the Bible

“In the merit of righteous women, our ancestors were redeemed from Egypt” (Talmud, Sotah 11b).

Our Sages are pointing to the acts of Miriam, the sister of Moses; Batya, the daughter of Pharaoh; and the midwives to the Hebrews. Also, a month before Pesah (which begins April 3), we celebrate the story of another female redeemer, Queen Esther, the hero of Purim (which begins March 4).

Of course these women are key to the stories, but were they redeemers?

The Talmud’s perspective is that the world was created good but is permeated by evil, most of it perpetrated by human beings. Evil may be murderous in the sense of taking a life, or it may be murderous to human dignity. In the stories of Purim and Pesah, the evildoers threatened death: Haman to the entire Jewish people, Pharaoh in his decree against newborn boys. We know from modern experience that what keeps a death-dealing culture in place is fear and humiliation, secrecy and suspicion. That was true in ancient Egypt and ancient Persia as well.

Sometimes one does not have the power to defeat those who wield the sword. But one can confront the beliefs and fears that infiltrate one’s mind. That is the meaning of redemption: It begins with freeing oneself from mental slavery to negative or evil thoughts, and that freedom subverts the death-dealers, generating action to nourish life instead. That is what the women in all these stories accomplished.

Esther, ensconced in the king’s palace, had no connection with her people, and with her uncle Mordecai only secretly, through messengers. When she heard of Haman’s decree that would destroy her people, she was terrified. Nevertheless, she mustered the courage to confront the king and his evil crony. “Who knows but that it was for this moment that you reached the position of queen?” Mordecai suggests to her (Megillat Esther, 4:14). It was now or never, and it depended on her.

In the Exodus story, likewise, the atmosphere is one of desperation. After Pharaoh’s decree against male newborns, Miriam’s father, Amram, divorced his wife, Yocheved, in despair; he could not bear to bring a child into this world. Miriam confronted him, accusing him of being worse than Pharaoh, who was killing only males, while Amram was withholding life from females as well. He listened, remarried Yocheved, and Moses was born.

The Hebrew midwives simply ignored Pharaoh’s decree. Batya, Pharaoh’s daughter, quietly rescued a Hebrew baby.

Were these acts greater than those of Moses, Aaron or Mordecai? Not necessarily. But the men, redeemers on the public stage, could also be competing for power and position. The women redeemed by creating a space for life in their inner worlds, even at the risk of their own. They subverted powers that ruled by intimidation. They were part of our prophetic tradition that challenged monarchies and elites, and insisted that we care for the unprotected, the widow and orphan, the helpless infant—whose life, physically or socially, was in danger. They were fulfilling the command “not to stand idly by the blood of your neighbor” (Leviticus 19:16).

Women knew then, as they do now, that every power structure deprives someone of life or quality of life. We must seek out the places where misuse of power threatens lives, causes anguish and chokes potential. May Purim and Passover bring a renewal of our Jewish potential for spiritual and physical redemption—for ourselves and others.

Tamar Frankiel, Ph.D., is president of Academy for Jewish Religion, California, in Los Angeles.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply