Books

Fiction

Book Excerpt: The Golem and the Jinni

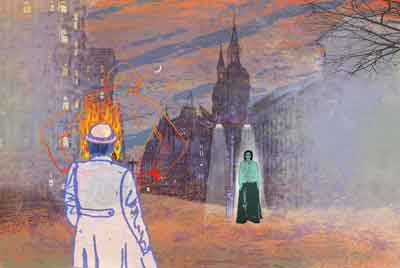

Chava is a golem, alone in the world after the man for whom she was created died on the journey to America. Ahmad is a jinni, jolted out of a silver flask by a Syrian tinsmith. In Helene Wecker’s spellbinding novel The Golem and the Jinni, these two figures try to make sense of the crowded immigrant neighborhoods of New York City in 1899, hide their identities and master their strengths and limitations. Inevitably, they meet one night, beginning a strange, fateful relationship. Wecker’s ability to turn folkloric characters of fire and earth into figures we relate to as if they were flesh and blood works magically—and won for her Hadassah Magazine’s annual literary award.

Until now, the jinni’s evening had been rather disappointing.

He’d taken advantage of the clear skies and gone out, but without much enthusiasm. Feeling uninspired, he’d planned to visit the aquarium again but found himself instead at City Hall Park, an unremarkable patchwork of lawn, broken to pieces by wide, intersecting concrete paths. From there, he’d made his way to the Park Row terminal shed, a long low building that stood on thick girders. He walked beneath it and looked up at the trains sleeping on their tracks, waiting to ferry the morning’s passengers across the Brooklyn Bridge.

He hadn’t been to Brooklyn, and he didn’t want to go, not yet. He felt he needed to parcel out these new experiences carefully, to keep from running out. He had a fleeting image of himself, ten, twenty, thirty years hence, wandering in ever-widening circles, exhausting every source of distraction. He rubbed at the iron at his wrist, then noticed what he was doing and stopped. He would not, would not, succumb to self-pity.

He wandered northeast along Park Row and realized he was nearing the Bowery. He had no wish to go back again so soon, so he took a random turning, and landed on a street lined with squalid-looking tenements. This, he thought, was no better.

The buildings on either side narrowed to wedges ahead of a large intersection, a cracked wasteland of pavement. Beyond lay a narrow, hemmed-in park. There was a woman standing alone at its center.

At first he only saw that she was a respectable- looking woman, out by herself in the dead of the night. Such a thing was odd, if explainable. But she wore no hat or cloak, merely a shirtwaist and skirt. And why was she staring at him, tracking his every move? Was she deranged, or merely lost?

He reached the middle of the intersection, and glanced at her again, unsettled; and saw that she was not human, but a living piece of earth.

He stopped cold. What was she?

Now he, too, was staring. Hesitantly he walked forward onto the grass. When he was a few feet from her she stiffened, and made to draw back. Immediately he stopped. The air around her held a breath of mist, and the scent of something dark and rich.

Now he, too, was staring. Hesitantly he walked forward onto the grass. When he was a few feet from her she stiffened, and made to draw back. Immediately he stopped. The air around her held a breath of mist, and the scent of something dark and rich.

“What are you?” he asked.

She said nothing, gave no indication she’d understood. He tried again: “You’re not human. You’re made of earth.”

At last she spoke. “And you’re made of fire,” she said.

The shock of it hit him square in the chest, and on its heels an intense fear. He took a step backward. “How,” he said, “did you know that?”

“Your face glows. As if lit from within. Can no one else see it?”

“No,” he said. “No one else.”

“But you can see me as well,” she said.

“Yes.” He tilted his head, trying to puzzle it out. Looked at in one way, she was merely a woman, tall and dark-haired. And then his vision shifted somehow, and he saw her features carved in clay. He said, “My kind can see all creatures’ true natures, it’s how we know each other when we meet, in whatever shape we may be wearing. But I’ve never seen…”

He reached out, unthinking, to touch her face. She nearly leapt backward.

“I shouldn’t be here,” she gasped. She glanced wildly around, as if seeing where she was for the first time.

“Wait! What’s your name?” he asked; but she shook her head and began to back away like a frightened animal.

“If you won’t tell me your name, then I will tell you mine!” Good: that had stopped her, at least for the moment. “I’m called Ahmad, though that’s not my true name. I am a jinni. I was born a thousand years ago, in a desert halfway across the world. I came here by accident, trapped in an oil flask. I live on Washington Street, west of here, near a tinsmith’s shop. Until this moment, only one other person in New York knew my true nature.”

It was as though he’d opened a floodgate. He had not realized until that moment how much he’d been longing to tell someone, anyone.

Her face was the portrait of a struggle, some inner war. Finally she said, “My name is Chava.”

“Chava,” he repeated. “Chava, what are you?”

“A golem,” she whispered. And then her eyes widened, and her hand flew to her mouth, as if she’d told the most dangerous secret in the world. She stumbled backward, turned to run; and he saw in her movements her enormous physical power, knew that she could easily bend one of Arbeely’s best plates in half. “Wait!” But she was running now, not looking back. She darted around a corner, and was gone.

He stood alone on the grass, for a minute or two, waiting. And then he followed after her.

She wasn’t very difficult to track. As he’d guessed, she was lost. She hesitated at corners, glancing up at the buildings and street signs. The neighborhood was a warren of slums, and more than once she crossed the street to avoid a man stumbling her way. The Jinni kept a good amount of distance between them but often had to duck quickly around a building when her confused path doubled back on itself.

At last she found her bearings and began to walk with more certainty. She crossed the Bowery, and he followed her into a somewhat cleaner and more respectable-looking neighborhood. From behind a corner he watched her disappear into a thin house crammed between two enormous buildings. A light came on in one of the windows.

Before she could look out and see him, he was walking away west, memorizing the streets as he went, the turnings and landmarks. He felt strangely buoyant, and more cheerful than he’d been in weeks. This woman, this—golem?—was a puzzle waiting to be solved, a mystery better than any mere distraction. He would not leave their next meeting to chance.

It was nearly dawn by the time the Golem returned to her boardinghouse. Her dress still lay on the floor, the torn fabric gaping like a scolding mouth.

How, how could she have been so careless? She shouldn’t have been alone on the street! She shouldn’t have wandered so far from home! And when she saw the glowing man, she should have run away! She certainly shouldn’t have spoken to him, let alone told him her nature!

It was the Rabbi’s death; it had made her weak. The glowing man had found her at the worst possible moment. And the force of his curiosity, his desire to know more about her, had overwhelmed what little self-possession she’d had left.

She’d have to be stronger than that now. She could afford few mistakes. The Rabbi was gone. She had no one left to watch over her.

The force of the loss hit her again. What would she do? She had no one to talk to, nowhere to turn! What did people do when the ones they needed died? She lay curled on her bed, feeling as though part of her chest had been roughly scooped out, left raw and exposed.

Finally she drew herself together and stood. It was time to leave for the bakery. The world hadn’t stopped, no matter how much she might wish it, and she couldn’t hide in her room. Feeling leaden, she put on her cloak, and heard something crackle in the pocket.

It was the envelope. COMMANDS FOR THE GOLEM. She’d forgotten.

She opened the flap, drew out a square of thick paper, torn roughly at its edges and folded twice. She opened the first fold. There a shaking hand had written:

The first Command brings Life. The second Destroys.

The second fold gaped open slightly, as though it could not wait to divulge its secrets. Through the gap she saw the shadow of Hebrew characters.

Temptation roiled inside her like a fog.

Quickly she folded the paper back up again, and stuffed it in the envelope. Then she put it in the drawer of her tiny desk. She paced for a few minutes, then grabbed it out of the desk, stuffed it between her mattress and the bed frame, and sat on top of it.

Why had the Rabbi given her this? And what was she supposed to do with it?

Excerpt from The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker © 2013 by Helene Wecker. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply