Being Jewish

Commentary

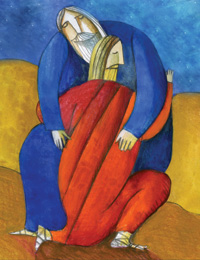

Continuity and Rebellion

We all know that Father’s Day is a secular American holiday, invented as a way of honoring fathers as a complement to Mother’s Day. Sometimes I wonder if there should be a Jewish Father’s Day—Yom Avot—and, if so, whom should we honor? a We might start, of course, with Abraham—Avraham Avinu, Abraham our father, the father of the Jewish people. But, let’s go back one more generation—to Terah, the father of Abraham, our people’s grandfather.

Why should we honor him? Because, as the late Rodney Dangerfield would have said, he gets no respect.

The Bible tells us almost nothing about Terah. He appears at the end of Genesis 11, and by the time Genesis 12 begins, he has already disappeared. A famous legend says that Terah was in the idol-making business and that young Abraham broke his father’s idols, thus becoming the first monotheist in history. Here is the paradox: The Jewish people, a people obsessed with intergenerational continuity, is itself born in a radical act of discontinuity.

And that is the way it has always been. Children rebel against their parents—sometimes becoming less religious and sometimes reclaiming ritual and spirituality for themselves. As the modern Jewish thinker Martin Buber said: “Religiosity [or spirituality] starts anew with every young person. Religiosity induces sons, who want to find their own God, to rebel against their fathers; religion induces fathers to reject their sons, who will not let their fathers’ God be forced upon them.”

The immigrant generation preserves its cultural and religious past; their children rebel, and the grandchildren rebel against the rebellion. An entire generation of American Jews, embarrassed by their parents and grandparents’ religious embarrassment, has reclaimed religious teachings that had been triumphantly placed in the trash bin of history.

So, here is the curious issue. Yes, Judaism believes in honoring parents. But, to create a people and a faith that would put honoring one’s parents in the very Holy of Holies of religious obligation—the Ten Commandments—it was necessary for the founder of that religious culture to dishonor his father. Says a midrash (Bereshit Rabba 58:5): Abraham was the only Jew in history who was exempt from honoring his parents. Had Abraham obeyed that mitzva, the Jewish people and all of Western religion would not have been born.

What, finally, happens to Terah? In the medieval Sefer Ha-Yashar, we read that Terah continued his idolatry business and there were no words between Abraham and his father. Then, one day, says the legend, Abraham returned to his father.

In my imagination, I see Abraham and Terah fall on each other, weeping—as fathers and sons will. I imagine Abraham saying to his aged father: “Father, come with me to the Land of Israel and you will know why I had to do what I did. It was time for a God we cannot see but Who sees us. It was time for a new vision.”

In the midrash, Terah did repent, and he came to know his son’s freshly discovered God. It took a while to get used to, but it happened. And God rewarded Terah with a long life, long enough that he was able to see his son’s glory and to see his grandson Isaac live to age 35.

And then, old and full of years, Terah died. He dwells in paradise, the sages say—where, presumably, he sits with his son, Abraham, and they dream together of a world that might yet come to be.

Jeffrey K. Salkin is a rabbi, writer and lecturer. This essay is adapted from his book The Gods Are Broken! The Hidden Legacy of Abraham, published by the Jewish Publication Society.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply