Israeli Scene

Personality

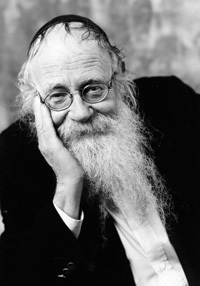

Adin Steinsaltz

One of Israel’s leading scholars, educators and philosophers, Rabbi Adin (Even-Israel) Steinsaltz, 77, has authored 60 books, the latest entitled My Rebbe (Shefa Foundation/Maggid Books), detailing his relationship with the charismatic leader of Chabad-Lubavitch, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who died 20 years ago. Steinsaltz was a follower of the Rebbe, assisting him in his education network in the former Soviet Union. Steinsaltz lives in Jerusalem.

Q. You spent a great deal of time with the Rebbe. What inspired you to write a book about him?

A. My book is about a personality who was hugely complex, [both] arcane and mundane. I don’t know if I’ve done him justice because it is very difficult to transmit something so challenging. The Rebbe was a great man…known to everybody because he filled a very public role, wrote and spoke to so many. He was also a very private person. My book is a point of introduction and connection for people to [get to know] an important, fascinating man. Also, even though transmitted insufficiently by me, [I want to see] that his message will somehow go further. If I had to boil down my thesis into one word, the Rebbe was wholly dedicated to one burning concept: redemption.

Q. How did Chabad, once a decimated Hasidic movement post-Shoah, become a huge force in world Judaism under the Rebbe’s leadership?

A. It is a baffling mystery. The Rebbe…emphatically did not want to be the head of anything. He wanted very much to sit and do his work quietly, anonymously. There was no ego in his remarkable deeds, and the power came from the message [of redemption] itself. The Rebbe’s truth was more shining than a diamond, and therefore it made a huge impact—on those who understood what he said and on those who didn’t even understand the words, those who looked into his eyes and those who simply read his speeches. He submitted himself totally to his duty and ultimately everybody came to him.

Q. What did the Rebbe say about the messiah, or moshiah, especially since after he died some of his followers were publicly calling him the moshiah?

A. He didn’t talk about moshiah in too many ways. It was for him perhaps the inner essence of everything he was trying to do. He was a man of one idea, and the idea is: What can we do to bring the messiah? He didn’t really care about some of the details associated with this, but every ounce of his being yearned for the messiah to come.

Q. In My Rebbe you write about the Rebbe being a “seer.” What do you mean by this?

A. Many years ago, when my son was 15 years old, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. The prognosis was poor. [My wife and I] asked the Rebbe for blessing and instructions. The Rebbe was deeply encouraging and blessed our son with a long life. However, he added that we should not permit a bone marrow transplant to be done. The doctors were furious when we chose to follow the Rebbe’s guidance, not theirs. Despite their prediction, our son healed, married and had children—without undergoing the transplant procedure. At a medical convention years later, the doctors admitted that, in specific cases like my son’s, their approach had been wrong. Almost none of the children in my son’s hospital unit survived. I don’t believe the Rebbe was a miracle worker, but he was a seer, and there was something very deep in the Rebbe’s insights. He had an outstanding memory and an ability to integrate information, so it could be that that also played a role in his insights into the human condition.

Q. You explain in your book that while other Hasidic rebbes had confidants and personal lives, the Rebbe himself was very lonely. Why was this?

A. Obviously, there’s no way to know for certain how he felt, but he spoke in public for some 50 years, yet never spoke about himself. He didn’t write about himself, either. Even before he took his leadership role, it was clear that he was a loner and a private person. Loners like the Rebbe have a clear purpose, a lifelong aim, and they focus on the work that they must accomplish. The Rebbe was like this. It is known, however, that his closest emotional ties were with his family: his parents, brothers and, later on, of course, with his wife.

Q. In the book’s epilogue, when you discuss the aftermath of the Rebbe’s passing, you differentiate between “losing a leader” and “losing a captain.” Can you elaborate?

A. Yes. A leader is necessary, important. A world without a leader is a confused place. The people are waiting for someone to make decisions and give guidance. However, it is worse when a ship loses its captain. A ship at sea is not anchored to anything, and so when the captain is gone, the crew has no directions and the people onboard are in a very precarious place. Without the captain, who will set that course?

Fortunately, for Chabad, the “captain” did set the intended course toward a destination. He prepared the charts. What I mean is that the Rebbe did not just leave a legacy; he left marching orders—to be better people; to aspire to change the world. In his last years, he used to tell people, ‘Open your eyes.’ Open your eyes and see. If you think people are only interested in power or money, you are mistaken. What they really want is a little bit of love. Those who seem to be striving only for power and for possessions are really striving for comfort and to hear a good word. Because he left these orders to better the world, the captain has set the course to bring the ultimate redemption, the moshiah.

Q. You are best known for your translation of the Talmud into contemporary Hebrew and English and other languages. You have devoted decades of your life—since 1965—to this work. Why is access to the Talmud by all Jews so critically important to you?

A. The Talmud is a central pillar of Jewish knowledge. It is not only important in and of itself, but it is organically connected to just about everything in the realm of Jewish knowledge, from the practical, everyday halakha to exciting and dizzying mystical notions. It has to do with poetry and with prose, with almost every conceivable aspect of Judaism. So having a connection with this central pillar means that a person has a chance to better enter the whole world of Judaism. Without Talmud, there is a gaping lack that cannot be filled.

Q. Your first translation was the now out-of-print The Talmud: The Steinsaltz Edition. Nine tractates of a new Hebrew-English edition, the Koren Talmud Bavli, are now in print. What is your goal?

A. We wanted to produce a beautiful, contemporary edition in English—many people do not understand the Aramaic text—that would enable people to read and understand the Talmud in a simple, basic format as well as to delve into many hidden notions and depths if they want to study it in a more profound way.

Q. What challenges did you encounter?

A. The Talmud went through centuries of censorship from the church. I went to ancient manuscripts and compared them and reintroduced those censored passages into the text. Another example: The Talmud discusses every area of life, science, geography, mysticism, idolatry, sexual issues. We do not leave out or gloss over even one of these controversial topics. We translate them and include them, as true to the original, authentic meanings as possible.

Q. Is there still interest in your Kabbala book The Thirteen Petalled Rose, which you wrote in 1980?

A. [The book] was not about Kabbala but rather a part of Kabbala, so it has the huge advantage of being authentic. People are still reading and studying it over 30 years later.

Q. Time magazine once referred to you as a ‘‘once in a millennium scholar.’’ How did you feel about that?

A. You must learn not to believe everything that is written in the newspapers. I hope people don’t take it too seriously. I know I don’t. We will see in another 500 years what people will have to say about Time’s observation.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply