Arts

Feature

By the Book

Miriam Schaer took apart the Bible she received at her bat mitzva. She cut the 45-year-old pages into the prayerful shape of her open hands, sewed them together, painted the book a deep purple highlighted with gold and beaded the spine.

She called her new personal prayer book Words of God Slip Through My Hands. Out of the remaining fragments she created a hand-shaped box to hold her doubts and questions about her relationship to Judaism and God.

A fragment of Hebrew poetry preserved in the Cairo Genizah captivated Detroit artist and printmaker Lynne Avadenka: The eight lines attributed to the unnamed wife of rabbi and liturgical poet Dunash ben Labrat, author of “D’ror Yikra,” may be the only poem written by a Jewish woman in medieval Spain. Avadenka used the poem in an accordion-folded artist’s book (a work of art realized in the form of a book) ornamented with tile-like calligraphic shards. She also juxtaposed the poem’s text with a backstory of her own creation in which Ben Labrat abandons his wife after the birth of their child and titled the piece Plum Colored Regret.

Brooklyn-based Doug Beube alters books, transforming them into sculptural works that are personal responses to political or social issues as well as art history. In Partition, a commentary on the wall Israel constructed to deter Palestinian terrorists, the cut pages of two books, The High Walls of Jerusalem: A History of the Balfour Declaration and the Birth of the British Mandate for Palestine, by Ronald Sanders, and Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land, by David K. Shipler, are set like wings into two L-shaped wooden bookends, symbolic of the options inherent in the situation of two peoples living side by side.

Schaer, Avadenka and Beube are all artists intrigued by the book as a vessel for creative expression. Though book art may sound like a synonym for illustration, it is a genre all its own, with a breadth of approaches and formats. It can be classic, edgy, personal, political, feminist, historical and more. It can resemble a book or a sculpture. It can riff off books as concepts rather than traditional objects. Scroll, tablet, codex, bound, unbound, wordless, digital: Book art encompasses them all.

In its most expansive definition, book art treats the book as a work of art. It includes anything an artist does within the form of the book—from page sequencing and structure to content or text, says Maddy Rosenberg, owner and curator of Central Booking in New York, a gallery and exhibit space that showcases book art. “The book,” she says, “is a jumping-off point.”

Given that Jews are often called the people of the book, it’s only natural that many artists who gravitate to book art are Jewish. Of the 160 international artists whose work Rosenberg has chosen for her gallery, about a quarter are Jewish (including Avadenka, Schaer and Beube). Many explore Jewish themes. “We are a people who read the same book every week and always find something new,” explains Avadenka. “We are connected to text, storytelling, repetition and a collective narrative.”

The intimacy and participatory nature of artists’ books is what interests creators and viewers. Instead of the “no touching” prohibition that distances viewers from most artwork, these books can be held, pages turned and contemplated at a private pace. “There is a one-to-one correspondence between the viewer and the object,” says Rosenberg, a printmaker and book artist herself. “When you hold a book you are feeling the artist who made it and every person who has touched it. It is a repository of history, filled with the energy of humanity.”

“A book is a container for ideas. It is an interdisciplinary site for an artist to explore,” says Schaer, 58, who lives and works in Brooklyn but teaches in the master’s program in book and paper arts at Columbia College in Chicago. As a volunteer at the bindery of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art 25 years ago, she discovered girdle books, small, portable prayer books or accounting ledgers that were attached to a monk’s girdle or waistband in medieval times. A fiber artist first, the clothing connection hooked her, and she decided to use the structure as a healing opportunity to explore feminist issues, especially the idealized female body. She has since also adapted brassieres, bustiers and gloves.

“Girdles are binders—like notebooks—places to hold and keep stories,” Schaer writes in an artist’s statement. She stiffens the fabric with a thin layer of acrylic; then paints, collages and inscribes the surface; and devises alcoves for further exploration. When Roses Cease to Bloom, based on an Emily Dickinson poem, is a Maidenform girdle painted blue and festooned with jingle bells; within the piece is a small pop-up book called a “tunnel book.”

Though it has been on the periphery of the art world, book art is now moving toward more mainstream recognition and acceptance. Artists’ books are displayed and collected by museums, libraries, colleges and universities, which will open their rare book rooms and special collections to visitors by appointment. Nonprofit centers that organize changing exhibits and workshops include New York’s Center for Book Arts, the San Francisco Center for the Book, the Jaffe Center for Book Arts at Florida Atlantic University Libraries in Boca Raton, Florida, and the Minnesota Center for Book Arts in Minneapolis. The Guild of Book Workers, a national organization founded in 1906, has 10 regional chapters with 850 members.

Most often, artists’ books are one-of-a-kind or limited editions, but sometimes a publisher will release a book that straddles the line. For example, Gefen Publishing’s And Every Single One Was Someone by Phil Chernofsky features only one word, “Jew,” repeated six million times.

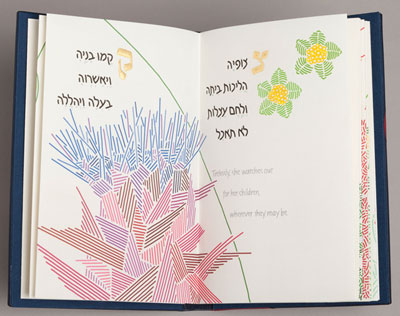

Some artists take a traditional approach to book art. Inspired by his father’s collection of almost 2,000 volumes of various editions of the five megillot, calligrapher and graphic artist Jonathan Kremer, 60, hand-lettered and illustrated the Hebrew text of Eichah, Lamentations. In another project, he fittingly nested the text of “Eshet Hayil” (Woman of Valor, an alphabetical acrostic from Proverbs) in the structure of an alphabet book, recast the English translation to reflect a contemporary sensibility and paired it with a panorama of Israeli wildflowers (also alphabetically arranged). One edition is on permanent display at Temple Beth Hillel-Beth El in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

“My mission is to interpret anew what is old,” says Kremer, a newly ordained Conservative rabbi and resident of Ardmore, Pennsylvania. His current project plays with the rabbinic requirement that a scroll contain a specific number of letters: His book will have one letter less.

People think they know what a book is, and when they experience what we have created there’s an element of surprise or subversiveness,” notes Avadenka, 59. Avadenka’s works—many of them take the form of limited-edition, foldout accordion books—are clean, spare and subtle, focusing on the beauty of a calligraphed word or simple woodcut. Her themes are both Jewish and universal. Root Words: An Alphabetic Exploration, a 77-inch-wide accordion book, was inspired by her search for commonality in Judaism and Islam. She learned that both Hebrew and Arabic have a three-letter-root system, that the word for compassion is the same in both languages (rahamim) and that it derives from rehem, womb. “Language is the root of the problem and also the only solution,” she notes. She invited calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya to collaborate on a harmonious blue-and-black abstract design that illustrates seven strong words in Hebrew and Arabic side by side (human being: ben adam, bnu adam); their text traces the origins of both languages.

Avadenka, who grew up in a Conservative home and travels to Israel frequently, came to book art from printmaking, Hebrew calligraphy and a love of reading. She has received commissions and awards from numerous Jewish museums and organizations, including the Hadassah–Brandeis Institute. Her work is in collections from the Israel Museum and Library of Congress to the New York Public and British Libraries; the University of Michigan and Skidmore College libraries have her complete works.

During a 2011 Jerusalem fellowship from the American Academy, a program of the now-defunct Foundation for Jewish Culture, she developed Jerusalem Calendar, made up of Hebrew and Arabic ephemera—calendars, flyers, newspapers—in a black, white and red palette. “It was like making a new alphabet for the city,” she says. Her love of literature has led her to create bilingual editions of the works of Israeli writers Dan Pagis, Shulamith Hareven, Amos Oz, Yehuda Amichai and A.B. Yehoshua. She recently received funding from the Covenant Foundation for an artist’s book and educational project based on the life and works of Zionist poet Rahel (1890-1931). Avadenka has also reworked four of the five megillot; Ecclesiastes is an ongoing project. By a Thread imagines a conversation between Esther and Scheherezade. Lamentations Suite was part of a 2013 exhibit at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York featuring book artists’ explorations of sacred Hebrew texts.

The “seemingly antiquated technology” of books is still purposeful in a digital age, notes Beube. The book itself is the raw material that he alters by cutting word by word with a Dremel drill. As he cuts, folds, gouges, pierces and excavates the physical properties of the book, changing its structure, abstracting its content and eliminating letters or words, he constructs his own text.

In Beube’s Vest of Knowledge, four black vests packed with pages of the 64-page Encyclopedia Britannica encased in clear vinyl tubes decry suicide bombings in Israel, Iraq and Afghanistan. Red wires attached to the vinyl tubes simulate the flow of blood and life. “The piece is a positive statement,” he says. “Let’s explode knowledge all over.”

In Exodus (part of the collection of the New York Public Library), he took a standard printed copy of the Book of Exodus and drilled the biblical text so that only one letter in each word remains, resulting in a frayed and frustrating experience. “The brain tries to assimilate and figure out the word but can’t,” he explains. “What has exited is the text.” The edges of the book are no longer flat, they feather out like a bird about to take flight, a metaphor for the Jews leaving Egypt.

In fact, Beube calls himself a “biblioclast” and has titled a monograph of his work Breaking the Codex. He uses the word codex, literally a block of wood in Latin, to reflect the undeviating, inflexible and limited capacity of the book. “That is its built-in personality flaw; that is its elegance,” he writes on his website. “I’m not interested in romanticizing the book,” he adds. “What’s important is the spine of the human being, not the spine of the book. I want my work to be controversial and thought-provoking.”

He distinguishes between repurposing a book and destroying it. “I won’t rework the Gutenberg Bible or a priceless book, just one that’s mass-produced,” he says, pointing out that he found the copy of Exodus on the floor of a Judaica shop.

Beube, 64, grew up in Hamilton, Ontario, in a Conservative family with roots in Russia and Poland. He began as a photographer with an eye for offbeat subjects. In graduate school at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, he learned about sequencing, relating one picture to another. “That started to imply books,” he says. “I realized if I put my photographs in a container it would need to be a book.” He also studied traditional bookbinding, learning to take books apart and put them together.

Though only some of his art has Jewish content, Beube is steeped in Judaism. In the sculpture Transport, he denudes softcover books of their covers and pages, leaving only the spines. They spill out of a pine box too small to hold them, ready for burial, resonant of the boxcars that transported people to ghettos and death camps. The Silent Question, based on a lecture that philosopher Martin Buber gave after the full extent of the Holocaust became known, reflects Beube’s own spiritual questioning. He turns a codex of the lecture into a scroll—its predecessor—made of diaphanous paper and gouged-out words. The voided text, he explains, invites the viewer to contemplate what is in the gaps. “How do we find God in nothingness?” Beube asks.

Beube often uses zippers as a metaphor for the cutting and pasting—zipping—on a computer. He places zippers along different parts of the world map, allowing him to produce limitless variations, with sections added or interchanged at will, a process that lends itself especially well to geopolitical issues that he maps both literally and figuratively. Amendment is an altered map that allows a viewer to physically zip other countries onto Israel’s borders (attaching Israel to the United States, for instance) and, in so doing, encourages viewers to ponder the entire political climate.

Schaer’s memory of missing words tackles the subject of absence in a personal way. When her father, a surgeon, died in 1998, she cut all of his letters to her, molded them into the shape of his palm, pasted his photograph into the palm and tied a black mourning ribbon on the book’s spine. “A lot of what he did I do,” she says, “cutting, sewing, taking things apart and putting them back together.”

Raised in the small Jewish community in Buffalo, New York, Schaer says she often felt like an outsider looking in—and still does. She is not observant, but much of her work decodes her relationship to Judaism. Tallis of Lost Prayer, an elaborate pink-and-tan 10.5-foot-long book, is made of thousands of hand-shaped pages cut, patterned and bound with leather cords and beads. Her show-stopping Eve’s Meditation, a wordless, five-inch-high, four-foot-long, purple snake-like book, is in the Allan Chasanoff collection—almost 350 pieces of mostly sculptural art recently gifted to the Yale University Art Gallery that examine the book under pressure in a digital age.

Schaer’s Jewish identity is rooted in family, especially the long lines of powerful women and good storytellers. Her installation, Solitary Confinements: A Family Portrait, dramatizes the place of the individual in family life. Each of the four figures standing at a bright yellow table set for a meal are large artist’s books constructed from pieces of clothing. They contain smaller books with narratives that viewers can remove and read. “We all have our assigned roles in the family structure,” she explains, “but our inside dialogue is different.”

As artists redefine books, they infuse the old adage “Don’t judge a book by its cover” with new meaning. Often, it is the sacredness of each person and an individual’s journey that artists’ books exalt. “There are thousands of books,” says Beube, “but each human being is unique.”

Online and On View

- Summer Invitational,” June 16-July 25, group exhibition, WCU Fine Art Museum, Cullowhee, North Carolina

- “Detroit Connections,” September 26-November 26, group exhibit, N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art, Detroit, Michigan

- “Rebound: Turning Books Into Art,” September 19-November 7, group exhibit, with Doug Beube, Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center, Birmingham, Michigan

- “Codex,” November, BravinLee gallery, New York, New York

- “Emendations,” November, Christopher Henry Gallery, New York, New York

- “Odd Volumes: Book Art From the Allan Chasanoff Collection,” October 10, 2014-February 1, 2015, group exhibit, with Miriam Schaer, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

- “Boundless: The Book Transformed in Contemporary Art,” through August 10, group exhibit, Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, Mesa, Arizona

Kremer’s book art is available at the National Museum of American Jewish History’s shop in Philadelphia.

- “Alternative Maternitites,” L’Atelier-KSR, Berlin, Germany

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply