Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: Utopia, Visions and Evolution

“In crowded Jewish quarters, deprived of air and sunshine, our bodies became weak.… Let us again be wide of body and strong of gaze,” stated Max Nordau, Hungarian-born physician, author and cofounder (with Theodor Herzl) of the World Zionist Organization. It was 1900, the Second World Jewish Congress.

Almost a decade later, 10 men and 2 women, educated East European Jews, founded the first kibbutz, Kibbutz Degania (wheat), south of the Kinneret in what was then Palestine. Within five years, the kibbutz had 50 members. Speaking Hebrew and working the land, these halutzim (pioneers) were in the forefront of a movement that became one of the hallmarks of the State of Israel. In a reduced and modified style, the movement still exists today.

Using photographs, videos and sound recordings, San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum presents “To Build & Be Built: Kibbutz History,” an exhibit about the kibbutz, its development and its present-day status. The show runs through July 1.

Divided into three chronological sections—Early Settlements, Communal Culture and Kibbutz Today—large black-and-white photographs tell most of the story. The images of kibbutzniks at work and at play are on loan from the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at the University of California, Berkeley; the Yeshiva University Museum in New York; HaShomer HaTzair Archives in Yad Yaari, Israel; Jerusalem’s Central Zionist Archive; and the Government Press Office of Israel.

“The kibbutz movement illustrates different ways of doing things and creating a community, themes that have a lot of relevance today, especially in the Bay Area, home to so much innovation,” says Claire Frost, curatorial associate at the museum.

As shown in Early Settlements, much of the land acquisition for the building of the kibbutzim (as well as the rest of what, in 1948, became the Land of Israel) was accomplished by the Jewish National Fund, established in 1901 at the Fifth Zionist Congress under Nordau and Herzl’s leadership. The iconic JNF blue collection boxes were placed in thousands of households worldwide; between the two world wars, the organization raised a million dollars. A negotiation with local inhabitants is illustrated in a 1932 photograph, A Meeting at Kibbutz Beit Alpha with Neighbor Bedouins.

The kibbutz movement’s principles included physical fitness, equality and self-reliance. The traditional occupations associated with East European Jewry—peddling, banking—were abandoned in favor of agriculture, associated with ancient Israel. Women would be men’s equals. Among the more startling images in the exhibit is Women Working at the Stone Quarry at Kibbutz Ein-Harod, from 1941. The shorts-and-sandals-clad women, looking energetic and happy, are pushing large, rock-filled mine carts along a railway track.

Ideals aside, many photographs still show women occupied in traditional women’s work—supervising children in nurseries, cooking food. However, women were generally not responsible for day-to-day child-care. Children were raised communally, playing, eating and sleeping together, visiting their parents only in the evenings. Cribs in Kibbutz Yavne (undated) shows babies in side-by-side cribs being watched over by a (woman) caretaker. Among the most striking images is one of boys and girls hanging in a geometrical formation from a play structure at Kibbutz Yagur in the 1950s. “A lot of people who grew up on a kibbutz talk about it in ideal terms, like an eternal summer camp,” says Frost, who curated the exhibit.

Agriculture was the kibbutzniks’ main occupation during the early decades; however, some of their goals were not realistic. Because of the region’s climate and soil, attempts to grow wheat proved unfeasible. Instead, citrus fruits and olives became staple crops. Orange Sorting (1934) shows workers surrounded by what appear to be tons of fruit. Even today, kibbutzim still supply 40 percent of Israel’s agricultural output.

The military was another source of occupations for kibbutz-dwellers. Since the developments were often located near the country’s boundaries, they became targets for the increasing conflicts with the British and the Arabs in the 1930s and ’40s. Possibly as a result, kibbutzniks formed a disproportionate number of military and political leaders: Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was the second child born in Degania, which was also the home of Prime Minister Golda Meir, war hero Joseph Trumpeldor and Zionist theorist A.D. Gordon. From 1949 to 1958, even though only 7.5 percent of Israelis lived in kibbutzim, they formed 20 percent of Knesset members.

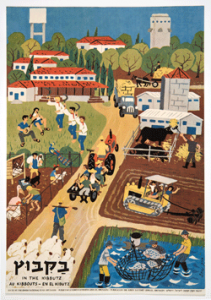

In the spirit of cooperation, shown in Communal Culture, the kibbutzim organized folk dancing and singing. The exhibit’s slightly enigmatic title, “To Build & Be Built,” comes from a folk song of the period that claims that those working the land would “build and be built”—creating both the culture and themselves at the same time. Record covers—Songs of Hope (undated) and Sing Palestine (1946)—demonstrate efforts to reach out to the wider world. Audio recordings reproduce some of the songs. A colorful poster, In the Kibbutz, issued by JNF, shows scenes of animal husbandry, fish farming and music making, with attractive houses set among trees in the background. Children help with the chores.

In addition to folk singing and dancing, cultural projects were emphasized. A photograph shows eight seated musicians playing against a backdrop of open landscape. Kibbutz-nurtured dance companies, choruses and orchestras traveled throughout the world (a video clip shows one of the dance troupes), and museums were established. Cultural activities as well as general meetings and meals were held in the hadar okhel (dining hall), which served as the central point for the kibbutzniks. The Special Night Squad Eat in the Dining Hall at Kibbutz Ein-Harod (1938) shows the men having a meal before going on guard duty.

Most kibbutzim were antireligious by policy, although a minority continued to practice traditions such as abstaining from work on the Sabbath and keeping kosher. A photograph shows men praying while wearing tefilin at Kibbutz Rodges during the 1930s. But holidays, while often preserved, were changed in emphasis. The most important holidays became Pesah and Shavuot, emphasizing the land, labor and agriculture. Shavuot Harvest Celebration, an uncredited photograph taken around 1950, shows a row of white-apron-clad women bearing food offerings at a celebration.

Inevitably, the kibbutz, like the rest of israel, has seen changes over recent decades. During the 1980s, influenced by worldwide inflation, globalization and a trend toward privatization, the institution began to move to a new model. Families rejected communal child-rearing and children moved into their parents’ homes. The movement’s socialist spirit weakened as, together with the rest of the country, political opinion shifted from the left to the center. Nonetheless, in 2010, there were still 270 kibbutzim in Israel, though the percentage of the overall population living in them has dropped significantly.

Although agriculture is still a major occupation, manufacturing and technology have become increasingly important. Combining the two, the kibbutz movement pioneered drip irrigation on Kibbutz Hatzerim in 1965. More recently, Kibbutz Ketura, started by former Young Judaeans, built the country’s first solar field, a model for others worldwide. Photographs show workers installing a drip irrigation system among date palms, and the solar field. Another venture into ecology and organic farming is depicted in photos of sheet mulching, a form of permaculture, practiced in several kibbutzim, some of which also conduct courses for visitors. Other enterprises include tourism; many kibbutzim now have rooms to rent to tourists. Swimming pools (Pool at Kibbutz Dafna, 2011) have become a fixture.

Kibbutzim are no longer exclusive to the countryside; urban kibbutzim feature cutting-edge architecture. Urban Kibbutz Migvan in the Town of Sderot, from 2006, shows attractive low-rise apartment buildings in a leafy setting. Another photo depicts contemporary buildings designed by leading architect Moshe Safdie at Kibbutz Shoval.

The kibbutz movement influenced American Jewish summer camps. In Santa Rosa, California, Camp Swig (originally Camp Newman) emulated kibbutz living during its existence from 1951 to 2008. Berkeley’s Urban Adamah, an educational farm and community center, “integrates the practices of Jewish tradition, sustainable agriculture, mindfulness and social action to build loving, just and sustainable communities,” according to its website. Practicing “organic farming, Jewish living, and social justice,” the organization offers educational programs and community celebrations. The exhibit includes photos of children at Camp Newman and Urban Adamah.

Though a small exhibition, and one that could have been rounded out with more art and artifacts, especially of the pioneer period, “To Build & Be Built” has received favorable response. Some comments in the show’s guest book criticize it for not including more information about kibbutz relations with Arabs. However, others who identified themselves as former kibbutzniks have left comments such as: “It is a very interesting exhibit that makes one want kibbutz all [over].”

As American cultural anthropologist Melford E. Spiro wrote in his 1958 volume, Children of the Kibbutz (Schocken), “The kibbutz, unlike most societies known to ethnography or history, practices comprehensive collective living, communal ownership, and cooperative enterprise.”

Or, as one visitor wrote in the guest book, “[The exhibit] brought tears to my eyes—strength, fortitude, faith and hope.”

Renata Polt, editor of A Thousand Kisses: A Grandmother’s Holocaust Letters (University of Alabama Press), lives in Berkeley, California.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply