Arts

Exhibit

Feature

The Arts: United (Jewish) Artists

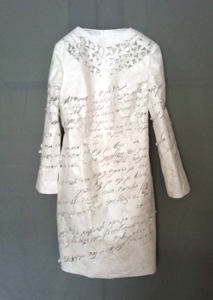

kittel collection. Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Nicholls.

On a sodden late autumn evening, I tromp through the byzantine streets of Spitalfields in the East End of London. A couple of wrong turns and drenched trouser legs later I find myself at the humble entrance to Sandys Row Synagogue, the oldest Ashkenazic synagogue in London. Sandys Row lies on a cultural fault line. It is at the heart of what used to be the city’s Jewish quarter and is now a mecca for artists. It is the perfect meeting place for the London Jewish Artists’ Salon.

The salon was started by artist Jacqueline Nicholls and arts producer Juliet Simmons in 2012 and has grown to well over 100 members, including artists of all stripes—sculptors, graphic novelists and performance artists—as well as students and scholars. While London has two major venues for displaying Jewish art, the Ben Uri Gallery and the London Jewish Museum, Nicholls and Simmons recognized a lack of opportunities for artists to interact. Their recipe is simple: Put a bunch of clever, creative Jews in one place, leaven with wine, cake and self-deprecating humor—all English specialties—and see what happens.

For artists like the young sculptor Benedict Romain, presenting his work at salons and seeing other artists share works in progress have pushed his art in new directions. “Though I come from a Jewish household, my surroundings, friendship groups and education have always been very secular,” he says, “and making Jewish art is something that did not occur to me previously, where now I have made a conscious decision to explore it.” This turn has begun to bear fruit for Romain, who is currently preparing for a show next summer at the London Jewish Museum called “The Invention of Ritual,” in which he will respond to some of the institution’s more eccentric examples of ceremonial art, from an Art Deco etrog container to a Kiddush cup with a moustache protector.

The salon formula is not unique to London. In recent years, Jewish art salons have been springing up around the world with increasing frequency. Some groups can claim an older provenance, including the American Jewish Artists Club, which was founded in Chicago in 1926 and continues to exhibit across the Midwest. However, the vast majority of Jewish arts societies date back less than 15 years. It is an exciting phenomenon whose success has even shocked many of the salon members themselves.

A watershed moment came in 1999 with the formation of the Artist Beit Midrash at the Skirball Center in New York by Rabbi Leon Morris and Tobi Kahn, a charismatic painter and sculptor. As its name suggests, the Beit Midrash brings artists together to study Jewish texts on a regular basis, challenging them to find new ways to visualize Jewish subjects. “It was a way for Jewish artists who were interested in Judaism and were already creating art to merge the two,” Kahn says.

Another pivotal moment came in 2004, when artist Ruth Weisberg founded the Jewish Artists Initiative of Southern California. The model there was different, assembling artists from Jewish backgrounds for collaborations but without focusing on producing work with explicitly Jewish content. Still, many JAI members participate in shows on Jewish subjects, including “Sacred Words, Sacred Texts” at American Jewish University in Los Angeles’s Platt & Borstein Galleries, which was on view from September 29 through mid-December.

For Dutch-born artist Yona Verwer, the driving force behind Jewish Art Salon in New York, both the Beit Midrash and JAI provided critical inspiration. Before she founded the salon in 2008, she says, “there was no community. Most artists did not know each other, nor did they know art historians, curators and writers.” Salon events, which quickly drew participants from around the country and even abroad, allowed artists to enjoy critical feedback from one another—something many had not had since art school—and provided a framework for wider exposure.

Though some artists had already exhibited prolifically, others have enjoyed their first major exhibitions as a direct result of contacts built through the salon. Several institutions have taken a special interest in salon artists, especially the JCC in Manhattan. In 2012, the JCC gave Nicholls her first solo show in New York, in which she displayed daily drawings inspired by passages from the Talmud as well as a collection of radically refashioned kittels, robes worn by Orthodox Jewish men for High Holidays, weddings and burial.

In Maternal Kittel, Nicholls stitches the message “How much does mummy love you?” on a tape measure, reminding us of the boundless love of a mother for her child as well as the challenges children can feel “measuring up” to parental expectations. In Modesty Kittel, Nicholls pinpoints the hypocrisy that can underlie demands for tzniut (modesty) among Jewish women. Pornographic images sown in white thread across the white blouse, invisible at first glance, pull us in and then indict us for our lascivious gaze. These daring investigations into her own identity as an Orthodox Jewish woman drew rave reviews in the Orthodox Jewish Press and The Jewish Week, in New York. Together, the critical and popular success of Nicholls’s show helped cement links between the New York and London salon scenes, prompting plans for a reciprocal exhibition by New York salonists in London.

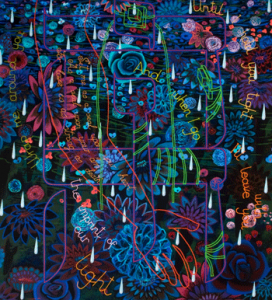

Image courtesy of Ben Schachter.

Yeshiva University Museum in New York has also hosted several shows with works by salon artists. In the 2012-2013 exhibition “It’s a Thin Line,” Pittsburgh artist Ben Schachter created maps of eruvim, creatively knitting together Jewish tradition and minimalist design. Tracing the perimeters led Schachter to reflect on his own boundaries as a Jewish artist. As he puts it, “Being a Jewish artist has made me a bigger fish in a smaller pond.”

Non-Jewish institutions have started to take notice of the salon, too. The exhibition “Contemporary Book Artists Explore Sacred Hebrew Texts” this past autumn at New York’s Museum of Biblical Art (MOBIA) showcased works by several salonists. The highlight was Siona Benjamin’s dazzling Megillah Esther Scroll, in which the Mumbai-born artist paints the Jewish heroine blue like a Hindu deity, a witty play on the sense of difference she feels as a “Jewish woman of color.” Perhaps because her work explores multiple forms of ethnic, national and religious difference, Benjamin has experienced success both inside and outside the Jewish art scene.

The Minnesota-based Jewish Women’s Artist Circle, founded in 2005, often exhibits in churches as well as galleries and synagogues. They meet frequently to consider different themes. Works from their most recent theme, the first chapter of Genesis, the Creation story, have appeared in the Basilica of St. Mary’s and the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis.

The friendships and connections forged by salons have also spawned other grass-roots projects. Last spring, Patricia Eszter Margit launched a pioneering artists’ residency program with support from Jewish Art Salon members. In its first incarnation, Art Kibbutz New York brought together 30 artists from around the world. Over the course of three weeks in Upstate New York, Margit invited artists to explore the “Jewish connection to nature.”

The results ranged from the subtle to the dramatic. Connecticut digital artist Cynthia Beth Rubin took samples from a nearby lake back to her studio-cum-laboratory, where she recorded videos of tiny microbes gliding and squiggling through the water. Enlarged and set to the stirring melody of “Lekha Dodi,” traditionally sung to welcome Shabbat, these dancing forms signify a sense of rebirth, a return to paradise fitting for a residency that took place at Eden Village Camp in Putnam Valley.

Nikki Green and Asherah Cinnamon also drew inspiration from the water, albeit on a completely different scale. In Shema: Listen, they created a massive wooden sculpture of the Hebrew letter shin. After crafting the 12-foot-wide sculpture from twisting branches, they marched it down to the nearby lake in a celebratory, communal procession, before setting it adrift. The next morning the artists set out together by canoe to locate the piece and anchor it near the shore. While they initially considered setting the piece ablaze in a sort of ritual sacrifice, Cinnamon says they felt it would be better left “as a gift to the lake and to Eden Village Camp. Setting it on fire seemed too violent an act, especially to me, given the tranquillity of the lake and woods.”

With all of these flourishing endeavors, we might ask whether the grass-roots Jewish art scene has reached its climax. Are there any gaps in this great expansion? Victor Majzner, a great furry bear of a man based in Melbourne, Australia, says emphatically that “there is no Jewish art scene in Australia.” While he notes that there are a few dozen accomplished Jewish artists scattered through the continent, only a couple produce works on Jewish subjects, and it has been difficult to arrange shows on Jewish themes.

For 30 years, Majzner has mostly gone about creating his own brand of Australian Jewish art from what he calls his “studio cave.” This hermetic practice has yielded hundreds of brilliantly colored canvases, which have formed the basis for books including his Australian Haggadah and Painting the Song.

In one of his most poignant works, Majzner meditates on the words of Song of Songs 8:6, “Love is as strong as death.” There are many ways to pick one’s path through the jungle of this canvas, for instance following the neon trail of phylacteries, which wrap around Hebrew letters like tendrils, or droop from them like Spanish moss. Death creeps into the canvas in the form of shimmering droplets of water, symbolizing mourning. And yet these tears are also waters of renewal, preventing this dazzling menagerie of flowers from wilting. Love challenges and conquers loss.

For Majzner, being a Jewish artist and engaging with Scripture in particular, has made him a fish out of water in the contemporary art market. “I am proud to be called a Jewish artist,” he says. “Unfortunately, since I started working seriously on Jewish ideas and content, numerous galleries stopped exhibiting my work.”

Even if they take a more sanguine view, almost all the Jewish artists interviewed have felt the tension between the wider art world and that of the Jewish artist scene. Nicholls admits being “frustrated” sometimes at being labeled a Jewish artist, and feeling a moment of doubt recently when looking at “all this Jewish stuff” in her resumé. Cinnamon, too, has wondered how this label affects her reception, although, she says, “at my stage of life, being a feminist Jew is so central to my being that I do not pay much attention to those fruit flies in my head.”

Verwer takes these anxieties as a challenge. “One needs to march to one’s own drummer,” she says defiantly. “It is time for Jewish art to move into the realm of ‘cool.’” She dreams of seeing images of the intricate Jewish amulets and charms that she depicts in her paintings projected on the façade of the Empire State Building and other New York landmarks.

For Verwer and others, salons have given Jewish artists a productive way to respond to their minority status within the art world. Salons provide a receptive environment for artists to discuss aspects of their work that the art establishment often misunderstands or outright disdains. These gatherings also provide artists, especially younger ones, with the self-confidence of belonging to a movement. They have also helped relieve deep-seated anxieties about the place of visual art within Jewish culture itself, since most of the artists felt that Jewish literature, theater and music receive far greater attention than Jewish art. Verwer even goes so far as to call the visual arts “the stepchild in the Jewish arts community.”

There are a couple of explanations for this. On the one hand, there is a longstanding belief that Jews do not, or cannot, produce visual art. This is usually based on the mistaken belief—common among Jews and non-Jews—that the Second Commandment, the so-called prohibition against “graven images,” is the last word on the subject of representation. In reality, of course, Jews have interpreted this commandment in numerous ways. From the third-century murals of the Dura-Europos synagogue in Syria to the canvases of Marc Chagall, countless Jewish artists have painted the human figure.

There is also a lingering prejudice among critics and curators that good art should somehow be “pure” and “universal.” This owes a strong debt to the late Jewish critic Clement Greenberg, a veritable lion in his heyday of the 1950s and 1960s. Greenberg insisted that Modern art should engage principally with the properties of its chosen medium rather than any external subject matter. Elements that seem indispensable, including the brushstroke, should be swept aside, Greenberg insisted, in a “process of self-purification.” Even today, visual artists who engage directly with Jewish subjects often find their work decried as “too Jewish,” an accusation seldom hurled at Jewish musicians and writers, even those who consistently engage with Jewish themes, such as Leonard Cohen or Philip Roth.

While many salons have addressed these prejudices by bolstering the profile of the visual arts, others have sought to integrate all the arts on an equal platform. This has been the mission of The Jewish Salons, a group with local chapters in Amsterdam, Prague, Vienna, Mexico City and Tel Aviv. The artistic director of the salons, Yasha Rozov—a funky Israeli designer—has helped organize evening extravaganzas in cities across Europe and South America, most recently in Kiev and Buenos Aires. The events, targeted at young people, involve music, interactive performance art and poster-making, and often culminate in debate.

At an event in Kiev called “Art in the Dark,” mimes and modern dancers took to the stage followed by klezmer musicians who passed out pots and pans and encouraged the audience to clink and clank along to the beat. In addition to grabbing the attention of young Jews, Rozov hopes that this kind of fusion will also be attractive to non-Jews interested in Jewish culture. He has noticed that “Jews will connect more to their own Jewish culture if they feel their peers are interested.” There is a strong connection, he says, between “being proud of your Jewishness and being inclusive.”

Jewish artists have begun to discover how salons might reshape their practice and their conceptions of what it means to be a Jewish artist in the 21st century. But they have only scratched the surface when it comes to engaging a wider public, both Jews and non-Jews alike. The idea of the Jewish art salon is still a work in progress. Like a freshly primed canvas, the best is yet to come.

Aaron Rosen, Ph.D., is lecturer in Sacred Traditions & the Arts at King’s College London. He is currently working on a book on religion in 21st-century art for Thames and Hudson as well as an edited volume called Religion and Art in the Heart of Modern Manhattan, forthcoming from Ashgate.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] Read full article here […]