American View

Feature

Letter from Boston: People of the Silver Linings Playbook

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Charles Dickens famously wrote in the opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities. He was describing Paris and London at the end of the 18th century, but for American Jews in the wake of the new Pew Research Center survey, his words turn out to be equally apt.

The Pew survey, entitled “A Portrait of Jewish Americans,” is the latest in a string of nationwide surveys of the American Jewish community dating back to 1970. Since the United States census is barred from asking questions about religion, only privately sponsored surveys—based necessarily on a representative sample of Jews, not an actual enumeration of all of them—can supply the data required for communal planning.

For decades, the Jewish community itself undertook these surveys. But after a debacle in 2001, when a $6-million survey proved to be fraught with problems and tremendously controversial, the Jewish Federations of North America decided that it would not sponsor such surveys anymore. So this time around, the survey was conducted by Pew’s Religion and Public Life Project. (Full disclosure: I was a member of the advisory board to the Pew survey.) Pew’s researchers had previously surveyed Muslim Americans, Evangelical Americans and Catholic Americans, among others, and they brought considerable methodological sophistication and experience to the project.

Their results, published on October 1, rocked the Jewish world. “American Jews Less Religious, More Likely to Intermarry,” one headline screamed. Another was titled “How America’s Embrace Is Imperiling American Jewry.” A third summarized the study in four words: “Soaring Intermarriage, Assimilation Rates.”

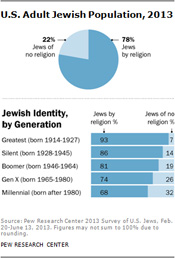

In fact, many sections of the study validate this “worst of times” portrait of communal decline. The percentage of Jews who describe themselves as “Jews of no religion,” for example, has increased significantly. Only 7 percent of those born prior to 1927 identify that way, while among young Jews born after 1980, the number leaps to 32 percent. The vast majority of these “Jews of no religion” belong to no Jewish organization at all and only about a quarter of them think that caring about Israel is essential to being Jewish.

With regard to intermarriage, the study’s findings are equally bleak. Some 17 percent of Jews who married prior to 1970 have non-Jewish spouses, according to the report, while 58 percent of those married since 2000 do. Among Jews whose own parents were intermarried, a whopping 83 percent have married non-Jews. Just 50 years ago, Jews were the least likely among all white Americans to marry outside of their faith. Today, the rate of intermarriage among Jews stands at about twice that of Muslims and Mormons.

In other respects, though, the Pew survey offers American Jews much to cheer about (“the best of times”). For one thing, the Jewish population of the United States has risen to 6.7 million, defined as Jews by religion as well as Jews “who say they have no religion but who were raised Jewish or have a Jewish parent and who still consider themselves Jewish aside from religion.”

Part of this Jewish population gain comes from approximately three-quarters of a million Russian speakers, immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their children. An additional 1.7 million American Jews are immigrants or children of immigrants from somewhere besides the FSU. Since the (much-disputed) National Jewish Population Survey of 2000-2001 counted only 5.2 million Jews, the new number is particularly welcome news. America’s Jewish population may be growing at a much slower rate than the American population as a whole, but at least it’s not falling.

Some 94 percent of American Jews, according to the Pew survey, proclaim that they are proud to be Jewish. Eighty percent say being Jewish is important to their lives. Three-quarters feel “a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people.” In an era of African-American, Hispanic and gay pride, it is perhaps not surprising that most American Jews express pride in their identity, but historically speaking it is heartening. A century ago, being Jewish in America was widely seen as a misfortune. In 1922, the great Jewish scholar Harry Wolfson went so far as to characterize being Jewish as a form of disability: “Some are born blind, some deaf, some lame, and some are born Jews.” Even in the 1960s, when I was growing up, everyone knew Jews who changed their names, fixed their noses and otherwise tried to cover up who they were. By contrast, today, being Jewish, partly Jewish or just of Jewish heritage is, for most Americans, something to boast about.

In expressing pride in their identity, marrying whomever they fall in love with and abandoning organized religion, American Jews very much resemble their American counterparts. Some 85 percent of all American young people (18 to 29), for example, say they have no problem with intermarriages, even interracial marriages that were illegal in some states as recently as 1967. Similarly, one-fifth of the United States public—and a third of all adults under 30—do not identify with any religion. The rise of “Jews of no religion” is thus by no means a unique phenomenon. Young people of all kinds are increasingly describing themselves as religiously unaffiliated, even if they also claim to be deeply spiritual.

Where American Jews do differ, and have for a long time, is in their religious behavior and their politics. On average, Jews attend religious services far less frequently than most Americans do and are, according to Pew, “among the most strongly liberal and Democratic groups in the population.” Orthodox Jews, about 10 percent of the American Jewish population, form the only exception: They attend services far more frequently than other Jews and are also more likely to be politically conservative and to vote Republican.

Lost amid the clamorous debate between those who emphasize the negative aspects of the Pew study and those who accentuate the positive are two surprising statistics that should be the focus of everyone interested in the future of the American Jewish community. First, about half of all Jews between 18 and 29 refused to identify themselves as Reform, Conservative or Orthodox. Instead, they told researchers they belonged to some “other denomination” or to “no denomination.” Looking ahead, this large pool of unidentified young people represents a huge opportunity. The future course of American Judaism will be determined by the decisions that these young Jews ultimately make.

Second, about half of all Jewish adults are currently unmarried: Many have never been married, others are widowed or divorced. This enormous pool of Jewish singles—more than twice the number of intermarried Jews—has received far too little attention from the organized Jewish community. If everyone paid more attention to the needs and desires of this forgotten half of our community, one suspects that there would be fewer Jews of no religion and that the intermarriage rate would go down.

Back in the early 1960s, American Jews estimated the community’s rate of intermarriage at 7 percent and assumed that most of its adult Jews were (or soon would be) married. Some 60 percent of America’s Jews belonged to synagogues back then, and the American Jewish Year Book reported exuberantly on the “flourishing state of the American Jewish community’s religious bodies,” with “increased congregational memberships,” many “newly established congregations,” “higher enrollments in…religious schools” and a “growing number of adult study groups and student programs.” Those were the “best of times” in 20th-century American Jewish communal memory, and the Pew report, from that perspective, looks like declension.

Three decades earlier, however, the majority of American Jews received no Jewish education whatsoever, the community was aging and its birthrate was in free fall. “The religious life of the Jewish people, its manifestation in synagogue and home, is at a low ebb,” Reform rabbis complained in 1931, at the depth of the Great Depression. Instead of being attracted to Judaism, young people, especially in the 1930s, flocked to Communism. “The Jewish religion as a social institution is losing its influence for the perpetuation of the Jewish group,” the Jewish sociologist Uriah Zevi Engelman concluded in a major article published in 1935 during those “worst of times.” He darkly predicted “the total eclipse of the Jewish church in America.”

Engelman’s gloom and doom prophecy serves as a timely warning to those who read the study as the death knell of today’s American Jewish community. And a look back at the 1960s reminds us that the news from the latest communal study could also be a whole lot better.

The best way to read the Pew study—and read it one should—is as a wake-up call, a diagnosis of communal strengths and weaknesses. As for the future, experience suggests that it is anything but predetermined. People change. Children return. What one generation seeks to forget, the next struggles to remember. The years ahead can be either the best of times or the worst of times. What they will be, in the end, is whatever we make of them.

Jonathan D. Sarna is the Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History and chair of the Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program at Brandeis University. He is the author of American Judaism: A History (Yale University Press).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people.” As historian Jonathan Sarna pointed out in an article reflecting on the Pew Survey, this is not surprising as we live in the era of ethnic, religious, sexual and gender-based pride. […]