Books

Personality

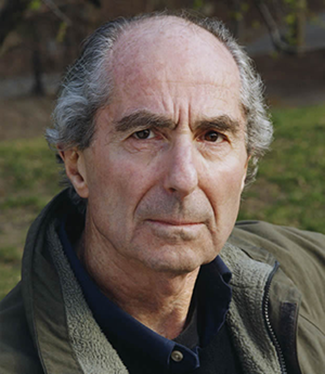

Philip Roth, New Jersey’s Native Son and Writer

The tour bus stopped in front of 81 Summit Avenue in Newark, New Jersey, and a cadre of unlikely sightseers—mostly professors of English—filed out excitedly in front of a literary landmark: Philip Roth’s childhood home. They milled around despite the rain, taking photos on the stoop and admiring the plaque designating the house a historic site. Unremarkable in its outward appearance, the Colonial-style home nonetheless served as the birthing place for one of America’s most remarkable writers—one who some scholars and critics consider the greatest living American novelist.

The tour bus stopped in front of 81 Summit Avenue in Newark, New Jersey, and a cadre of unlikely sightseers—mostly professors of English—filed out excitedly in front of a literary landmark: Philip Roth’s childhood home. They milled around despite the rain, taking photos on the stoop and admiring the plaque designating the house a historic site. Unremarkable in its outward appearance, the Colonial-style home nonetheless served as the birthing place for one of America’s most remarkable writers—one who some scholars and critics consider the greatest living American novelist.

The tour of Roth’s Newark was part of an 80th birthday celebration this past March honoring the man and his work and marking his retirement from writing. Since Roth’s announcement last year that he has said what he wanted to say—and has penned his last novel—he has been profiled and feted in many forums.

The Philip Roth Society, a group of readers and scholars devoted to the study and appreciation of Roth’s works, organized the festivities in Newark as an opportunity to ponder and praise Roth through an academic conference, a literary tribute and a bona fide party complete with champagne toasts and a marching band. A lavish cake was shaped like a shelf of Roth titles with an edible typewriter that the author himself cut.

Other tributes include The Library of America’s publication of a 9-volume series of Roth’s 31 works—from Goodbye, Columbus (1959) to Nemesis (2010); PBS aired a documentary called Philip Roth Unmasked (part of its American Masters series); and the Newark Public Library mounted “Philip Roth: An Exhibit of Photos from a Lifetime,” featuring 100 images from Roth’s own collection.

Roth has given over the task of writing his life to biographer Blake Bailey, granting him unlimited access to his archives and correspondence. In fact, Roth posted a note on the computer in his New York apartment on the Upper West Side that reads, “The struggle with writing is over.” “I look at that note every morning,” Roth told The New York Times, “and it gives me such strength.”

Roth has won every literary prize there is—some repeatedly—short of the Nobel. As a masterful architect of the lyrical sentence, he has mesmerized generations of readers.

“He is the most perfect tuning fork of the written word of any period,” said friend and writer Edna O’Brien at the Newark tribute. As a provocative explorer of masculinity, writing, childhood, aging, post-World War II American history and the American Jewish family, he has also nettled his share of readers.

“He writes books that bite and stay with you like a blow to the head,” said New Yorker literary critic Claudia Roth Pierpoint in Philip Roth Unmasked.

Seated onstage at the newark Museum, Roth described his obsessive rummaging in memory for thousands of concrete images like the bicycle basket in which he carried home half a dozen library books as a child. “The passion for specificity,” he said, “is at the heart of the task to which every American novelist has been enjoined since Herman Melville and his whale and Mark Twain and his river: to discover the most arresting, evocative verbal depiction of every last American thing. Concreteness…is fiction’s lifeblood. From this physicalness the realistic novel derives its ruthless intimacy.”

He enjoyed this task until three years ago, he said, when he awoke one morning with a smile on his face, “understanding miraculously that I had at long last eluded my lifelong master: the stringent exigencies of literature…. I’ve described my last javelin throw, and my last stamp album, and my last jewelry store, and my last breast, and my last butcher shop, and my last family crisis, and my last unconscionable betrayal and my last brain tumor of the kind that killed my father.” Dressed entirely in black, balding, with a tiny, mischievous smile playing around his mouth, he opened a black binder that held a copy of a graveyard scene from his novel Sabbath’s Theater, including a list of tombstone inscriptions. He read it to his captivated audience with a gentle inflection, relishing his own words and chuckling occasionally.

Author Jonathan Lethem recalls that his first encounter with Roth’s writing exposed him to a “long readerly sickness” he still endures, a sickness stemming from “opening oneself to a voice as torrential and encompassing, as demanding and rewarding as Roth’s.” Roth, he says, closed the distance between Saul Bellow and Mad magazine. Roth’s books, he added, “aren’t Jewish because they have Jews in them. The books are Jewish in that they won’t shut up.”

Roth, however, objects to being labeled an American Jewish writer. “I don’t write in Jewish,” he says in the documentary. “I write in American. I’m an American. Therefore I’m an American writer.” Yet his connection with the Jewish community is indisputable. It began explosively with his first book, Goodbye, Columbus and Five Short Stories, which depicts Jewish life in postwar America. The book won the National Book Award for fiction and the title story was made into a 1969 film starring Ali McGraw and Richard Benjamin. Yet, many Jewish leaders condemned Roth for his unflattering portrait of American Jewish life.

“I was assaulted as an anti-Semite and a self-hating Jew,” says Roth in Philip Roth Unmasked. “I didn’t even know what that meant. It didn’t dawn on me that it would cause a conflagration. It was a spontaneous and immediate response to the world I came out of.”

Bellow’s review in Commentary magazine zeroed in on Roth’s early genius: “Goodbye, Columbus is a first book but it is not the book of a beginner. Unlike those of us who came howling into the world, blind and bare, Mr. Roth appears with nails, hair and teeth, speaking coherently. At 26, he is skillful, witty and energetic, and performs like a virtuoso.”

Ten years later, the best-selling Portnoy’s Complaint, a ribald and erotic representation of Roth’s middle-class Jewish world, complete with possessive mothers, psychoanalysis and unremitted sex, catapulted him to celebrity and ratcheted up the Jewish community’s displeasure.

With the passage of time the controversies faded: Roth is now embraced with pride as a native son. He has experimented with political satire and fantasy, and created an alter ego in Nathan Zuckerman, star of many of his books. “Sheer playfulness and deadly seriousness are my closest friends,” he told author Joyce Carol Oates in an 1974 interview.

His later books have been hailed as masterpieces. Sabbath’s Theater, considered by many to be Roth’s best, is the story of over-the-hill puppeteer Mickey Sabbath and harkens back to Portnoy’s outrageous transgressiveness. Politics and history enter Roth’s work in his American Trilogy; he posits an alternate reality in The Plot Against America: Charles Lindbergh is elected to the White House instead of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. American Pastoral, a Pulitzer Prize winner, is a reflection of the failures of American idealism. His last book, Nemesis, explores the effects of the polio epidemic on the Newark community.

“Roth practically invented the genre of factual-fictional autobiography,” says Derek Parker Royal, founder and executive editor of the journal Philip Roth Studies. “His thinly veiled Zuckerman books follow the protagonist’s path from aspiring young writer to compromised celebrity to older man facing death.” Because of Roth’s first-person voice and his sly penchant for writing himself as a character in some of his books (The Facts, Deception, Patrimony and Operation Shylock), readers often mistakenly assume his characters are him. “I’m inventing Mickey Sabbath’s horniness,” says Roth in the documentary. “I’m not horny writing it.”

“Roth is the most slippery of writers,” says David Gooblar, author of The Major Phases of Philip Roth (Bloomsbury Academic) and program chair of the Roth Society. “As soon as scholars try to pin him down he takes delight in going in another direction. It’s hard to find a comparison with a writer who has written so many books at such a high level in so many different directions.”

It can be a challenge to teach Roth to a younger generation that does not identify with the battles of ethnic groups and assimilation, and writing that focuses extensively on masculinity. “Roth has had a harder time being appreciated in the U.S. than in India and Slovenia,” says Gooblar. “He is also sometimes misunderstood for being so local. His reach is much deeper and wider than that.”

Gurumurthy Neelakantan, a professor of English at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, praises Roth’s sense of urgency. “I come from a traditional Brahmin family,” he says. “He challenges any beliefs you hold, like the idea in the Human Stain that purity is a myth.”

Roth is the son of American-born parents: Herman, an insurance salesman, and Bess, a housewife. He grew up in the lower-middle-class Newark neighborhood of Weequahic along with his older brother, Sandy. “American writers leave where they come from and write about it for the rest of their lives,” says Roth, who has cast Newark as an integral character in his work. He recalls that there were no books around his house; his mother read books she rented from the local pharmacy. More than his favorite writers, Roth’s parents were a defining influence on him, O’Brien said.

Roth began to read with relish when he was 12 and devoured James Joyce. “That changed everything,” he said. He received his B.A. in English from Bucknell University, his masters in English literature from the University of Chicago and wrote short stories in the Army. Later, he taught creative writing at the universities of Iowa and Princeton and comparative literature at the University of Pennsylvania, and endured periods of great solitude writing at his Connecticut home. He married twice, the last time to actress Claire Bloom.

No bar mitzva pictures made it into the exhibit at the Newark Library, but there was one of his Galician grandparents, Sender and Bertha Roth; a shot of 1-year-old Philip at bat in Weequahic Park; photos of Bradley Beach family vacations; and with authors and friends Aharon Appelfeld and Cynthia Ozick. Roth included a photo with David Ben-Gurion, which sparked an anecdote he told curator Rosemary Steinbaum: “You know what Ben-Gurion said to me? ‘You see that cloud? It’s a Jewish cloud. You see that bird? It’s a Jewish bird. You see that tree? It’s a Jewish tree.’” Roth put that speech in the mouth of a character in The Counterlife.

O’Brien offered some examples of Roth’s prodigious energy and zest, every moment filled with jokes, anecdotes, invective, ribbing. “To live at that pitch,” she said, “that cerebral altitude, must be a very lonely place, not unlike the trapeze artist.” The other side of him, she said, “is a man who listens with such intensity and intent.”

Roth, she said, is a complicated man of contradictions: “feared and revered; hermit and jester; lover and hater; foolish but formidable…. He’s paralyzingly funny and morally rigorous. He’s at the top table of the literary echelons but he’s not of it. He’s too unpredictable. He’s a frugal man but also capable of great generosity. He’s the most sedulous reader I’ve ever come across; he gets to the pith.” His books, she added, are filled “with the ebullience he likes, the precision he insists on, the occasional blasphemy and something else deeper—the gravity, the artist’s dissection of the hemorrhaging of faith and hope in our world gone berserk.”

O’Brien recalled that Roth is partial to a quote attributed to Joyce: “‘Don’t talk to me about literature. Do it.’” For over 50 years, he did exactly that.

Rahel Musleah, a frequent contributor to Hadassah Magazine, runs Jewish tours to India and speaks about its communities.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply