American View

Feature

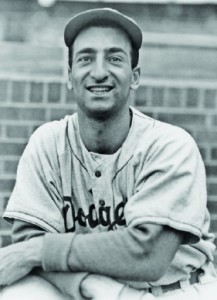

Letter from New York: Jewish Stars of the Diamond

Photo courtesy of the New York Yankees.

Most Jews, whether or not they are baseball fans, know the story of Sandy Koufax choosing not to pitch the first game of the 1965 World Series because it was Yom Kippur. In 1934, future Detroit Tiger Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg made a similar decision, choosing to sit out a game to observe that holiday. a Both decisions educated Americans about Jews. In fact, the poet Edgar Guest paid a memorable tribute to Greenberg’s decision to sit out the game. The last stanza read:

We shall miss him on the

infield and shall miss him at

the bat,

But he’s true to his

religion—

and I honor him for that!

Greenberg and Koufax also helped make Jews feel comfortable in America. Jews saw that they, too, could be accepted as Americans while simultaneously remaining true to their faith.

Important as these decisions were, more difficult High Holiday dilemmas were faced by other players who were not as talented as Greenberg or Koufax. Jesse Levis, a backup catcher for several teams during the 1990s, played a game on Yom Kippur for the Milwaukee Brewers in 1996. When his manager learned about the conflict after the fact, he apologized to Levis for putting him in the game. Levis looks back on the event—and his failure to speak up—with humor: “God punished me anyway…. We had, I think, maybe another week to go and I was 0 for 10 the rest of the year. He got me.”

Even Greenberg, exalted for his Yom Kippur observance, chose to play in 1934 on Rosh Hashana after consulting with a rabbi. In this way, Greenberg acted like most other American Jews by partially observing the High Holidays. Indeed, examining the oral histories of several Jewish major leaguers sheds light on some of the central issues American Jews faced during the 20th century, including anti-Semitism, black-Jewish relations and World War II.

One hundred and sixty-five Jews played major league baseball between the 1870s and the end of the 2010 season. Lipman Pike, who played in the 1870s and 1880s, is regarded as the first Jewish professional baseball player. Six players—including African-American Elliott Maddox—converted to Judaism. Jews, who made up about 3 percent of the population in the United States during the 20th century, made up less than 1 percent of baseball players from 1871 to 2002, the latest year for which complete figures are available. But their collective accomplishments are surprising.

Through 2002, the .265 Jewish batting average was 3 percentage points higher than the overall average. Jewish pitchers were 20 games over .500 and threw 6 of baseball’s first 230 no-hitters. A recent influx of top-flight Jewish major leaguers—Shawn Green, Kevin Youkilis, Ryan Braun and Ian Kinsler, for example—have likely boosted these statistics. With all these talented players, self-deprecating jokes about Jews and athleticism no longer make sense.

The classic High Holiday dilemma is just one theme that emerges from examining the experiences of Jewish major leaguers. Two other issues are: how players from various generations confronted anti-Semitism and racism, and how mid-20th-century players dealt with World War II service.

Until the past few decades, anti-Semitism was prevalent on the baseball field. Taunts about the size of a player’s nose and heckling based on the stereotype that Jews are cheap were common. (To be fair, taunts about players from other ethnic backgrounds were also common.)

Even into the late 1960s and early 1970s, first baseman Mike Epstein, who began his career with the Baltimore Orioles, remembers “that if we went into a restaurant, some of the players would expect I had ‘short arms,’ that I wouldn’t pick up the check. Even though it wasn’t true, it was something they’d heard.”

The players reacted in similar ways to the anti-Semitic heckling—sometimes from the opposing bench: They ignored it at first and then used their fists. In particular, Al Rosen, who was an amateur boxer before becoming an all-star third baseman for the Cleveland Indians in the 1940s and 1950s, was not shy about fighting.

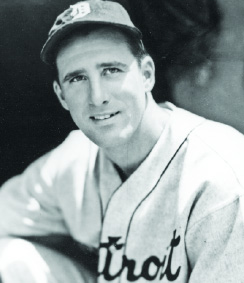

Rogers Photo Archive.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the world had changed. For the most part, blatant anti-Semitism was no longer acceptable among players.

Racial awareness was another important factor for players in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Most Jewish players understood some of the prejudices that black players faced—and some, like Cal Abrams, felt a special bond with their black teammates.

“I associated with them because we had a rapport about being with each other,” Abrams says of his black teammates on the Brooklyn Dodgers, including Jackie Robinson, the first African-American in the major leagues.

Some Jewish players stood up for their black teammates. Ed Mayer, who pitched for the Chicago Cubs in 1957 and 1958, remembers one of these times when he was in the minor leagues:

We were traveling from Montgomery through Georgia. And we stopped, and everyone wanted to buy a Coke. The machine was outside of a gas station, and there was a guy on my team from San Diego, a black guy who later became a famous pitcher, Earl Wilson. So, we all get off the bus to buy a Coke and Earl goes to put his nickel in the machine and the cracker attendant comes out and points a gun at him and says, “No N— is going to buy a Coke out of my machine.” I jumped in front of him and pushed him back on the bus and bought him his Coke.

For his part, Greenberg offered some encouraging words to Robinson. In an article written for Look magazine after his retirement, Robinson recalled an incident from his inaugural season in 1947—which was Greenberg’s last. Greenberg was playing first base, where Robinson was standing following a single. “He suddenly turned to me and said, ‘A lot of people are pulling for you to make good,’” Robinson wrote. “‘Don’t ever forget it.’ I never did.”

Often, however, players felt powerless to change the status quo, as Rosen explains:

[Black players in Southern towns] weren’t allowed to stay in the hotels, they weren’t allowed to ride in the taxi cabs—and it was a horrendous experience for them. And I always felt very badly about it and you might say, ‘Well, what did you do about it?’ Well, there’s very little that can be done in a situation like that.

There was another arena that affected some baseball players. Those who fought in World War II experienced conflicts between their career and their service. First, the players of that era who served, like all soldiers and their families, made huge sacrifices. Many interrupted their lives and their careers to serve, some of them for up to four seasons. For most, however, it was a relatively easy call.

Individual experiences of war are complex. For some, military service was the most important time of their lives. Moe Berg was a good-field, no-hit catcher who closed out his major league career with the Boston Red Sox in 1939. It was often joked that he could speak several languages and could not hit in any of them. During the war, Berg, a Princeton graduate, worked in Europe as a spy for the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Following the war, however, he was unable to find a steady job.

Mickey Rutner didn’t regret his service, but it hurt his chances of playing in the major leagues and earning a good living because he had to return to the minor leagues after he got out of the Army. After the war, Rutner became a career minor leaguer who only played a few games in 1947 for the Philadelphia Athletics in the American league.

Even those who are jaded about the big money and drugs that seem to pervade major league baseball today, make heroes out of players, Jewish or not. There’s value to finding heroes, especially for our children, who need someone to idolize and, in the best cases, emulate. Jewish baseball history is American Jewish history. We can be proud when outfielder Gabe Kapler and hitter Adam Greenberg represent Israel, either as players or coaches for the Israeli national baseball team that narrowly missed qualifying for the 2013 World Baseball Classic.

It is also important to look at players, past or present, as human beings who made imperfect decisions for imperfect reasons. Learning the complicated reality about players like Levis, Rosen and Rutner makes it easier for us to relate to them.

It is also important to look at players, past or present, as human beings who made imperfect decisions for imperfect reasons. Learning the complicated reality about players like Levis, Rosen and Rutner makes it easier for us to relate to them.

What are we supposed to do with star player Ryan Braun, whose suspension at the end of 2011 for using performance-enhancing drugs, was overturned, but on a technicality, and was recently suspended for 65 games in baseball’s latest steroids scandal?

There are few clear answers. But this contradiction is what history, whether Jewish, sports, personal or family, is all about.

In any case, there is no denying that Jews have had a significant past—as well as present—in baseball.

Peter Ephross is the editor, with Martin Abramowitz, of Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words: Oral Histories of 23 Players (McFarland).

Rogers Photo Archive.

Important Dates in Jewish Baseball History

September 19, 1934 The Detroit Tigers’ Hank Greenberg sits out a game in observance of Yom Kippur.

September 21, 1941 The New York Giants feature four Jewish players on the field at the same time: Sid Gordon and Morrie Arnovich in the outfield, Harry Feldman pitching and Harry Danning catching. This is the only time in major league history that four Jewish players from one team are on the field at the same time.

October 6, 1965 The Los Angeles Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax sits out Game 1 of the 1965 World Series in observance of Yom Kippur.

September 25, 1966 The Chicago Cubs’ Ken Holtzman defeats Sandy Koufax and the Los Angeles Dodgers 2-1 in a pitching duel between the two Jewish pitchers with the most career wins.

April 6, 1973 Ron Blomberg of the New York Yankees becomes baseball’s first designated hitter, a new position that allows one player per team in the American League to bat without playing the field. In recent years, Blomberg has embraced the honor, and his Jewishness, by calling himself the “Designated Hebrew.”

May 23, 2002 Shawn Green, playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers, goes 6-for-6 with 4 home runs, 7 runs batted in and sets a major league record for total bases in one game with 19.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply