Books

Fiction

The Kindest Cut

Be kind, my father would say to me from as far back as I can remember, and for a long list of situations. Be kind, he’d say, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle. The saying was from Philo, he’d told me, and I grew up imagining that the name belonged to the man who’d invented the kind of pastry dough you use to make strudel or spanakopita. When I was ten or eleven, though, I found out who Philo was, and the way it happened tells you things about my father you wouldn’t suspect from the quiet, somewhat shy man he was most of the time.

I was changing out of my uniform after a basketball game at our local YMCA on a Sunday afternoon when my father came into the locker room to see how I was doing, and while we were going over the game, one of the guys along our row of lockers called another guy a faggot. Without hesitating, my father walked over to the boy, told him that using such a term was vulgar and unacceptable, that he hoped the boy would never use it again, and that, to this end, he intended to speak with the boy’s father. My father waited for the boy to get dressed, after which he accompanied him to the Y’s lobby, where he told the boy’s father—a huge guy, six-three or -four, wearing a Boston Bruins hockey shirt—what had happened.

When the man told my father to mind his own business, my father repeated what he’d said to the boy: that use of such a word was vulgar and unacceptable and it demeaned not only the person to whom it referred but, more profoundly, the person who had the unexamined need to employ the word.

The man laughed in my father’s face, then jabbed him in the chest, told him that it took one to know one and that he’d better watch out or he’d wind up skewered butt-first on a flagpole. Grabbing the front of my father’s shirt, the man said that he bet the last time my father got lucky was probably when he’d found a box of Girl Scout cookies.

A woman at the Y desk picked up a phone—a crowd had gathered—but my father gestured to her to put it down and, very calmly, he addressed the man, and the way he did it made me think ‘Uh-oh!’ because although my father could be polite and accommodating most of the time, when he was seriously roused—watch out!

“Sir,” he said to the man. “Allow me to inform you that I have known more good women in my lifetime than have ever existed in your imagination.”

The man warned my father not to be a professor wise guy, made a fist and said the only reason he’d been holding back was because he didn’t like to hit little old men who wore glasses. At this point, my father, who was five-foot-six and weighed perhaps one-fifty, handed me his glasses, stepped forward, and pointed to the ceiling. “Well, look at that,” he said, and as soon as the man looked up, my father stomped down hard on one of the man’s feet and let loose with a swift one-two combination to the guy’s midsection. When the man doubled over, my father gave him a terrific roundhouse chop to the side of the head that dropped him straight to the floor.

“In my youth, you see,” my father said, “I studied at the Educational Alliance on the Lower East Side with the late, great intercollegiate champion Colonel David ‘Mickey’ Marcus, and I also had the good fortune to take several lessons at the Flatbush Boys Club from the equally great Lew Tendler, who himself had learned the trade, in and out of the ring, from the immortal Benny Leonard.”

The man opened his eyes but stayed where he was while my father advised him never to discount the benefits of a good education in teaching us that the use of verbal insults against those we deem inferior only served to reveal our own shortcomings.

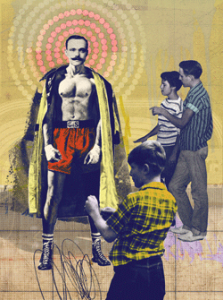

After word of the incident got around, my father became a hero to my friends who, when they hung out at my house, would ask him for boxing tips, and it turned out that my father knew more than a little about the sport. He had published a novel, Star of David, when he was in his early twenties, and it was based in part on the life of Barney Ross, a Jewish boxing champion who’d also been a war hero and had, from the morphine they gave him for pain when he was wounded, become a drug addict, and then a recovered drug addict. My father had been a pretty good bantamweight himself in Police Athletic League competitions, though he never did A.A.U. or Golden Gloves, and when my friends asked, he’d offer them basic stuff about feints and jabs and being alert to an opponent’s weaknesses and, using Ross as an example, about the will to win, which derived, he asserted, from fighting for something larger than yourself.

After word of the incident got around, my father became a hero to my friends who, when they hung out at my house, would ask him for boxing tips, and it turned out that my father knew more than a little about the sport. He had published a novel, Star of David, when he was in his early twenties, and it was based in part on the life of Barney Ross, a Jewish boxing champion who’d also been a war hero and had, from the morphine they gave him for pain when he was wounded, become a drug addict, and then a recovered drug addict. My father had been a pretty good bantamweight himself in Police Athletic League competitions, though he never did A.A.U. or Golden Gloves, and when my friends asked, he’d offer them basic stuff about feints and jabs and being alert to an opponent’s weaknesses and, using Ross as an example, about the will to win, which derived, he asserted, from fighting for something larger than yourself.

My friends would become entranced any time my father told them stories about Ross: how Ross’s father was a Talmudic scholar who owned a grocery store in Chicago and was killed by gangsters in a holdup, and how the family was made so poor by the father’s death that two of Ross’s brothers, along with his sister, were placed in an orphanage. The result was that whenever Ross was in the ring, he’d imagine he was fighting against his father’s murderers, and when he won the first of his three world championships, he used the prize money to rescue his brothers and sister from the orphanage.

After telling us about Ross—or about Tendler, or Leonard, or “Kid” Kaplan, or Abe Attell, or Daniel Mendoza, or other great Jewish fighters—and after giving us some pointers, he’d stop, hold up an index finger to indicate that the most important advice was coming, and then touch his tongue with his finger and emphasize that because it could produce words that allowed you to avoid a fight, or if you had to fight, allowed you to distract your opponent, the tongue remained your most important weapon.

And always, always, he would add, be kind—fight as hard as you can, but never forget to nurture the kindness in your heart, the way Barney Ross did. And one time, when a friend asked if the saying was from Ross, my father said no, that it was from Philo. I asked who Philo was, and my father explained that Philo had been a philosopher from Alexandria who lived about fifty years before Christ, and that even though he was known as Philo-the-Jew, scholars believed he’d been instrumental in the founding of Christianity by combining elements of Greek mystery religions with Jewish theology.

My father usually had answers to most questions my friends asked, and if he didn’t, he’d say, “Now that’s an interesting question—may I get back to you on it?” In truth, I grew up in awe not so much of things like his boxing expertise, but of his mind, of its sheer range and intelligence, though he would dismiss praise from me or anyone else by acknowledging that yes, maybe he had a few smarts, but if he did they were merely a result of the lucky genetic hand he’d drawn at birth.

In this, he said, he liked to think he had something in common with James Michener, though my father’s own writing—his one novel, along with a few short stories and two books about other writers (Ford Madox Ford and A.J. Liebling)—could not compare with Michener’s work, either in output or style. Although Michener had a low reputation among academics, my father considered him “a great humanist,” and would outrage his colleagues at Amherst College—something he never minded doing—by teaching a course every few semesters on Michener’s novels.

He owned all of Michener’s more than fifty books, and to encourage students, he would point out that Michener (whom he referred to as “the Rabbi Akiba of fiction”) hadn’t published his first book until he was past forty years old. Like Michener, my father was gifted with a photographic memory: If he read a page once, he had only to relax enough to locate the page somewhere in his mind and the sentences would be there for him. It was clear early on that I lacked not only his intellect but his phenomenal memory, yet it didn’t seem to bother him that I wasn’t drawn to matters intellectual or literary. I was never an especially good student, but as long as I applied myself, did the best I could and, what my father considered most important of all—remained curious about the world—he was satisfied.

“The wonderful thing about you, Herbie,” he said to me on the afternoon of my college graduation—repeating what he’d said on previous such occasions: my bar mitzva, my graduations from junior high and high school, and what he’d say each time I started a new job or brought home a new girlfriend—“the wonderful thing about you is that you’ve never disappointed me.”

Sometimes I wondered why. It wasn’t that I’d screwed up terribly, but more that I’d never succeeded especially well at any one thing: I hadn’t married, or bought a house or an apartment, or made a ton of money, or—the nut of the thing—ever had any clear idea of what I wanted to do with my life. More to the point, and what worried me from time to time: I’d never had much of a desire to do anything in particular with my life.

But when I’d say this to him—that I sometimes wished I was more like this person or that person, friends who’d become doctors or lawyers or teachers or businessmen, who owned homes and had kids and the rest—he would seem puzzled. Why did I compare myself to others? “Think of yourself as having taken the scenic route,” he’d say. Or he’d tell me that in this I was really just a quintessential man of my times—a free agent, much like those professional athletes who moved to different teams and cities every few years. And weren’t we, after all, all free agents these days?

By the time I was in my late twenties, his words of praise, along with the repeated injunction to be kind to everybody, especially when it came to the shits of the world, left me pretty cold. Why be kind to people who were mean and screwed over other people? Why forgive people for unforgivable acts? For all his sophistication and his knack, especially when it came to women and books, to discerning crap from quality, he also had a surprising willingness to suffer fools gladly.

I must have seen myself as one of those fools, since I had a fairly well-developed talent for depriving myself of those things—like sticking with interesting women who actually liked me, or making sure to spend quality time with my father—that might have offered more focus and direction, and more comfort and joy. Thus my tendency to change jobs (and girlfriends) regularly, to find jobs far from home and to stay away from home for years at a time.

When my father died, I was living in New York City, renting a 350-square-foot studio apartment on the Upper West Side while teaching math at an Upper East Side private school, and even though I was less than three hours away by car from Northampton, Massachusetts, I hadn’t visited my father there for nearly a year. His wife of thirty-one years—my mother—had died eight years before, at fifty-seven, from an aggressive form of lymphoma, and he’d taken early retirement soon after that but had stayed on in the home in which they’d lived, and in which my sister, Florence, and I had been raised. The rabbi of our synagogue called me with the news and told me he believed my father’s death had been relatively painless—that he’d become short of breath while swimming at the Y, had gone home and telephoned his family doctor. His doctor told him to go to the emergency ward at Cooley-Dickinson Hospital, and that he would meet him there.

They never met. They found my father at home, slumped over on our living room couch, cell phone in hand. He was sixty-nine years old, and it pissed me off that he hadn’t even made it to the proverbial three score and ten—that, to use language he was fond of, his number had come up long before it should have.

I rented a car and drove up to Northampton that evening. My sister, four years older than I, flew in from Cleveland that night with her husband, Larry, and their three children. The funeral took place the next afternoon. We honored my father’s wishes—he’d left specific instructions—and sat shiva in the traditional manner for a week, with all mirrors covered, hard wood benches for me and Florence to sit on, and with the rabbi cutting the lapel of one of my good jackets with a razor instead of pinning on a piece of black cloth.

On the day we got up from shiva, Florence and I met with my father’s lawyer, who said he would arrange for the probate and, eventually, if we wished, the sale of the house. Florence and I said we’d return in a month or so to divvy up furniture and other things we might want to keep, though I wondered, with embarrassment, where, given the size of my New York apartment, I would put things. Florence urged me to consider moving into the Northampton home, rent-free—the mortgage had been paid off years before—and look for work nearby. “As Dad liked to put it,” she said, “let’s try to see where the opportunity in an unwelcome situation might lie, okay?” I said I’d think it over.

I drove back to New York City that evening and returned the rental car. I felt numb. I’d made small talk all week with family, neighbors and some high school friends who’d come by. I’d wept for a minute or two at the cemetery, but that was it, and I told myself that the fact that my father was gone—that I’d never be able to talk with him again or see him or touch him—would make itself felt by and by. What I wanted to do, mostly, was to sleep. To sleep for hours, days, weeks or months so that I wouldn’t ever have to talk with anyone again.

When I entered my building—the hall light was out—someone grabbed my arms from behind while another man clapped a hand across my mouth and clicked open a switchblade.

“Make a wrong move and you buy it,” he said.

I nodded my agreement, and he took his hand away, and when he did I felt a river of rage begin to surge upward from my groin. When it reached my mouth, I spoke softly.

“Got it,” I said. “Sure. I’ll give you want you want—but look up there—the bulb’s gone—”

When the guy with the knife looked up, I stomped on his foot, ripped my arms free from the guy holding me from behind, and jammed an elbow as hard as I could into his gut. Then I chopped down on the other guy’s arm with my fist to knock the knife away and started swinging away with abandon. I thought of warning them that my old man had just died, that he’d taught me a thing or two and they didn’t know who they were messing with, because when I was roused—and oh boy was I roused!—there was no telling what I might do.

But the guy with the knife slashed me across the cheek—I felt the cut an instant later, warm blood flowing at once—and then smashed me in the mouth, told me to shut up and just hand over my wallet. I started to reach for my wallet and, still possessed, plowed into his midsection as if I were a fullback plunging for the goal line. He fell over, the other guy jumped on top of me, and then they beat the living crap out of me.

When they were gone, I walked to the local police station, filled out a few forms and got a cop to take me to the emergency ward at St. Luke’s Hospital, where they stitched me up, took X-rays and advised me to see a dentist as soon as I could. Did I want to press charges?

“You bet,” I said, and we drove back to the precinct house where I filled out more forms, put together a list of what was in my wallet—credit cards, driver’s license and the rest—and made some calls. Then I took something from my pocket and handed it to the cop.

“What’s this?”

“The billfold from one of the guys,” I said. “When we were rolling around on the floor, I picked his pocket.”

“Good going!” the cop exclaimed, and began examining what was in the billfold.

“We know this guy,” he said. “Oh boy, do we! You’re gonna make a lot of people around here happy if you press charges.”

He told me they’d be in touch after they brought the guy in, and that they’d want me to come down to ID him before we went to court. He drove me home in a squad car, and while I looked out at the empty streets—it was nearly midnight—I wondered, when I got to court and saw the guys who’d ambushed me, just how kind I’d want to be.

Jay Neugeboren’s latest book is The American Sun & Wind Moving Picture Company (Texas Tech University Press).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply