Israeli Scene

Personality

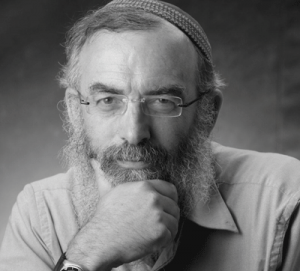

Interview: David Stav

Rabbi David Stav, 53, is founder-president of Tzohar, a network of national-religious rabbis. Unconventionally, Stav, Israeli-born chief rabbi of Shoham, in Israel’s central district, has been running a public campaign for Ashkenazic chief rabbi, based on the pillars of inclusiveness, mutual respect and Zionist commitment.

Q. The Israeli rabbinate—now headed by haredi Ashkenazic and Sefardic chief rabbis—has the last halakhic word on who is a Jew, marriage and divorce, burial, conversion, kashrut and even prayer at the Kotel. How do you respond to those who want the chief rabbinate abolished?

A. The main idea of Israel’s chief rabbinate is its vital role in maintaining the unity of the Jewish people in the State of Israel. To ensure this goal, to guarantee that we won’t be torn up into multiple nations—each one questioning the identity or legitimacy of the others—we need an infrastructure that all parts of society can agree on. We absolutely need one umbrella that welcomes under it all elements of Jewish society.

Q. If elected chief rabbi, you have said you would privatize kosher certification and require prenuptual agreements. What else would you do?

A. The chief rabbinate council will open the zones of marriage, which means that no longer will a couple be [forced to go to] their local rabbi. They will be able to open their marriage file wherever they want. This will be a quiet revolution, creating competition to improve services [instead of maintaining] a monopoly. Once the municipality and the religious council of that city see that their own young people are fleeing, they will see that they are losing both the goodwill of the community and income. The rabbi will be pressured by his peers to do a better job.

Q. Would you get involved in the Women of the Wall’s attempts to bring a feminist presence to the Kotel area?

A. As chief rabbi I will have to be involved. If there is goodwill from the Women of the Wall and there is goodwill from the rabbinic figures who supervise religious services at the Wall, things can be resolved. Part of the problem is there’s not enough goodwill and way too much publicity, which leads to inflexibility. We need to search for the practical solutions that might satisfy every side.

Q. Do you really expect to find much goodwill?

A. I hope it’s there. I [feel there is a lot of] overreaction in the way the police behave with the Women of the Wall. I am not at all sure that there is a will to find a solution from both sides because each side gains something from continuing conflict. In a perfect world, nobody should coerce the Orthodox to pray in a way that they don’t want to and nobody should prevent other people from praying in a different, respectful way.

Q. What about gender segregation on haredi bus lines and communal strife between haredim and the national-religious community in places like Beit Shemesh?

A. We should differentiate between two things: The way groups want to behave among themselves, and the way they try to impact on the general society. If someone wants to have a gender-separated wedding, no one should interfere with that. On the other hand, when people coerce other people in a public area it [is] our duty to reduce tensions and encourage solutions so that no one will feel coerced.

Q. Why would the ultra-Orthodox, who have controlled the chief rabbinate for a decade, support you?

A. I want to differentiate between haredi people and their political leaders. Many of the haredi grass roots don’t care [about some of the changes I want to make] because few among them want to carry on their shoulders the responsibility for the distrust that exists for so-called ultra-Orthodox Judaism. I think many will welcome our spirit of change. The politicians, I imagine, will fight against these important changes, and I’m ready for it.

Q. Why is it that you have the support of many non-Orthodox Jews, even non-Orthodox rabbis, as well as key political parties that will take part in the election, such as Yesh Atid, Yisrael Beiteinu and Hatenua?

A. Most of my support is from Israelis who do not want to define themselves as part of streams. Most Israelis are not Orthodox, yet are also not affiliated with any non-Orthodox stream—even if occasionally the synagogue they put their foot into is an Orthodox one. Beyond this, most of them hunger to be more exposed to Jewish heritage. What they find in my approach is…that I try to respect everybody without regard to which kind of yarmulke he wears on his head or if he wears a yarmulke at all. People are pleased that [Tzohar rabbis] don’t try to be coercive. We try to teach people our way, but we give full respect and dignity to others.

Q. Why is the chief rabbinate relevant to diaspora Jews? What is your approach to those who are not Orthodox?

A. Within the guidelines of halakha, I am willing to be as open as possible and I feel strongly that there is a need to increase the level of dignity between all streams of Judaism. In particular, there is a problem with olim…who are fully Jewish but are not recognized as such when it comes to aliya. We want them to be able to get married halakhically in the State of Israel. Therefore, the way the system helps them to prove that they are Jewish is exceptionally important. Every year we have hundreds of cases of Americans who made aliya and we in Tzohar are the only ones to help them prove they are Jewish. When we are in the office of the chief rabbinate, we intend to establish the infrastructure that will be able, on a national level, to help all Jews who want to make aliya and want to be a part of the Jewish people, to help them prove that they are Jewish and not abandon them to this quest on their own.

Q. And what about Jews who do not make aliya?

A. The chief rabbinate should be a key address for dialogue between the Jewish people in the diaspora and the State of Israel. The chief rabbi must also have a role in the relationship between religions. I have taken part in fascinating dialogues with Christians and Muslims. Regarding the relationship between Israel and the diaspora, the chief rabbinate has to take a very important role in helping Jews worldwide to cooperate with partners on many issues that we share.

Q. Tzohar is widely respected. What are its goals?

A. We started this organization after the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. We believed that the tension between different parts of Israeli society, manifested in a bitter divide between the right-wing camp associated with the religious and the left-wing camp associated with the secular, was the most existential threat we faced as a nation. We started with weddings—helping young secular couples get married—in Israel, with joy, not as wedding refugees in Cyprus where they go to escape the bureaucracy and limitations that come with marriage under the religious authorities in Israel. [In 2012, 9,000 Israeli couples married in civil ceremonies outside of Israel.] We continued with bride counseling and organizing prayers outside formal synagogues, in cultural centers, on Yom Kippur. We moved to celebrating many holidays for people who rarely enter the synagogue. We started a project called Shorashim [roots] to help North and South American immigrants prove they are Jewish, which is necessary to secure their immigration under Israel’s Law of Return. We are talking about 1.3 million people who had to prove their Jewish identity. At times we laugh and say we started as an organization to bridge gaps but now we are totally dedicated to helping Israeli society survive the social challenges that exist in the expanding divide between the religious and secular camps.

Q. There is an upsurge in religious Zionism, especially in the recent elections. Is the focus moving from Land of Israel and settlement issues to social and economic ones?

A. The religious Zionist movement realized that these social areas were neglected in the last two decades. We paid a price for that. Many Israelis don’t see a political solution for the century-long Arab-Israeli conflict and, therefore, people understand that what will drive our existence in Israel are our internal issues rather than external ones. More people are refocusing on values and how we treat each other, and this is also growing within the religious Zionist movement.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply