Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: Israel’s American Canvas

Image courtesy of Thierry Goldberg Gallery.

On a foggy Sunday in January, the hip boutiques, cafés and art galleries in New York’s Lower East Side teem with young locals who could have stepped right out of an episode of the popular HBO series Girls. The L.E.S., as the area is now often called, is home to some 60 galleries, at least three of them presently showing the work of Israeli artists.

Amid garment and luggage shops on Orchard Street is On Stellar Rays, where the large graphite drawing of zeppelins en masse in the small group show is by Zipora Fried. A native of Israel who has lived in New York for 15 years, Fried’s drawings and sculptures often feature odd and compelling accumulations of objects and markings.

Courtney Childress, associate director of the gallery, shows me computer images of stunning large-scale landscapes from the artist’s recent show in Miami. (Fried was one of 17 artists from Israel featured in the 2012 NADA Art Fairs in Miami.) “Zipora collects landscape images,” Childress says, “and in these new works she layers them digitally.” The results, even reduced to screen size—in real life they are 55 by 82 inches—are lush and haunting. They are reminiscent of the ethereal earthscape photographs of Ori Gersht on view, at that moment, in solo shows at The Jewish Museum in New York, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and at the Gund Gallery at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio.

Down Orchard, across Delancey and past the Tenement Museum is the tiny Sasha Wolf Gallery. I enter and stand for a while contemplating a photograph of an adoring mother and a naked, weeping child immersed in a bathtub called Bath, by Jerusalem-born Elinor Carucci, whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker and in New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Pictures by Women.” Bath, it turns out, is from “Born,” a photography series chronicling, with sometimes jarring intimacy, Carucci’s pregnancy, the birth of her twins and motherhood. It is mesmerizing. If Caravaggio had done domesticity (and photography), this is what it might have looked like.

Finally, I walk a couple of scruffy blocks east to Norfolk Street to the newly relocated, brightly lit Thierry Goldberg Gallery to attend the opening of Maya Bloch’s exhibition. It is easy to see why Bloch’s work has been likened to Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon’s and has attracted influential collectors and attention from The New York Times, the Huffington Post and The New York Observer. The intense, staring faces looking out from her oil-and-acrylic canvases are amplified and distorted visions inspired by found snapshots of other people’s families. I am particularly drawn to Eight Figures, a group of somber people gathered around a table. A wartime Seder? Partisans planning a mission? The anger, fear, confusion or plain sadness in their eyes is almost chilling. Bloch tells me she completed the piece upon returning to her Tel Aviv studio after two weeks of not being able to go there during the 2012 rocket attacks from Gaza. “I have two children,” she says. “It was the first time I felt really frightened because of my children.”

Familiar” series. Image courtesy of Andrea Meislin Gallery.

The gallery, owned by Israeli-born Ron Segev and his wife, Claire Lemetais, who is French, represents two other Israelis: video artist Oded Hirsch and Naama Tsabar, a sculptor and performance artist. But Segev feels it is important to maintain “an international roster, not just Israeli. It’s better for the artists that way.” The gallery is also a microcosm of the Israeli art scene in the diaspora today.

Not that long ago, exhibitions of Israeli art in the United States were mostly the purview of Jewish museums, synagogues, Jewish organizations—and Michael Hittleman’s eponymous and pioneering Los Angeles gallery, which opened in 1976.

But today, paintings, sculptures, installations, videos and digital works and, especially, photography by Israeli artists turn up everywhere.

At any given time—timing is everything, since gallery shows are often only open for a few weeks—you are likely to find art from Israel at galleries in Chicago or Houston or Palm Beach. However, New York, as an epicenter of the art world, is the main city for viewing Israeli art in America.

Hittleman’s gallery still offers arguably the most comprehensive selection of Israeli art in the country, from “old masters” such as Mordechai Ardon, Yohanan Simon and Yosef Zaritsky to contemporary masters like Joshua Neustein, Larry Abramson, Moshe Gershuni, Aram Gershuni (who Hittleman called “a fabulous young realist painter”) and Jan Rauchwerger.

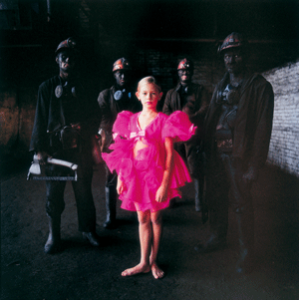

This past winter, in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood there were exhibits by art world superstar Michal Rovner and rising star Rona Yefman. Closing in January was “Sailboats and Swans,” an exhibition of portraits by Michal Chelbin at Andrea Meislin Gallery. (The exhibition can be viewed at the gallery’s Web site.) Like Diane Arbus, Chelbin, whose works are owned by venues such as the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, focuses on outsider subjects. Her previous project at the gallery was “Strangely Familiar.” It looked at the world of performers and wrestlers across Eastern Europe, England and Israel. Included in the series is the haunting Alicia, Ukraine, 2005, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In “Sailboats and Swans,” Chelbin’s camera is trained on men and women incarcerated in Ukrainian and Russian prisons. The title is ironic, referring to the improbable décor—fairy-tale murals—she found in some of these institutions, against which she set some of the inmates, many of them hardly more than children.

Chelbin traveled to Ukraine and Russia—her family’s roots are there—over a period of six years to work on this project. She spent hours with each of her subjects. However, she did not find out why they were behind bars until after photographing them, “drawing what is hidden to the surface,” as the novelist A.M. Homes put it in the exhibition catalog. “She captures—we shudder,” as we stare back, for example, at the sad eyes and hard face of Sergey, Sentenced for Sexual Violence Against Women. He is seated at a table in front of a wall painted with a bucolic forest scene in a prison for boys, and his unclenched hands, resting palms down on the table, look disproportionately large, predatory.

In another portrait, calmer on the surface but equally disturbing, a woman in a white nurse’s uniform oversees a group of toddlers in a rainbow- and bluebird-bedecked nursery. She could be any worker in any day care center. She is Vika, Sentenced for Murder, and the nursery is in a Ukrainian prison for women with children. As the reality of Vika sinks in, it brings on a true Chelbin moment, raising a morass of questions, knocking down obstacles to empathy.

About 80 percent of the names on the Meislin gallery’s list are Israeli, many of them high profile (Micha Bar-Am, Michal Safdie). The gallery began in March 2004 as a temporary exhibition of photography from Israel in a second-floor space in Chelsea. It coincided with Sotheby’s first New York auction of Israeli and International Art and the annual Armory Show and was intended to help raise awareness of contemporary art in Israel. Rivka Saker, founder of Sotheby’s auction house in Tel Aviv, asked Andrea Meislin, recently returned to New York after two years as research associate director of photography at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, to curate the show.

“Opening night ended up being a benefit for Bezalel [art school],” Meislin says. “There were tons of people… and they were buying things. I really didn’t imagine anybody would buy anything. We just wanted to show people what was happening in Israeli photography.” Meislin became a gallery owner, opening her first major exhibit in September 2004—a solo show of Barry Frydlender’s groundbreaking CinemaScope photographs, which are made by meticulously assembling composites of hundreds of images of the same scene. “We worked very hard to get the photo curator from MoMA in to see the show,” Meislin recalls, “and he sent an assistant first, and then he came in and he said, ‘I don’t know what I’m looking at, but I know I like it.’ He bought The Flood that day.”

Courtesy of Andrea Meislin Gallery.

Many sales later (including, recently, Ilit Azoulay’s series “Room #8” to the Centre Pompidou in Paris), in 2012, Meislin moved to her current location, a prime ground-floor space in the heart of Chelsea’s art district.

Saker, meanwhile, went on to found the independent nonprofit organization Artis (pronounced “art is”), which supports the work of Israeli artists wherever they may be, and has significantly accelerated, for many of them, the art world version of the process of natural selection. As Nancy Berman, director emerita of the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles and a board member of Artis, puts it, “A lot of contemporary Israeli artists were what I call mainstreamed already.… They are going to art schools in New York or London, or live in Berlin; they often are in art fairs, or in a gallery, and so curators get to know about them…. There was a lot going on…it just needed someone to shine a light on it.”

Artis, based in New York with outposts in Tel Aviv and Los Angeles, became that light. In addition to giving grants to artists and organizations, Artis sponsors research trips to Israel for curators and other art professionals. The trips give them a grounding in local culture and enable them to forge connections with counterparts and artists. “Ninety percent of the people who have come on our trips have done something with what we have provided,” says Yael Reinharz, Artis executive director.

Often, it is something impressive— like the six-figure purchase by Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art of Shirat Hayam (Song of the Sea), Frydlender’s masterpiece portraying Israeli soldiers in a semicircle, facing the Mediterranean, during the historic withdrawal from Gaza, after then-chief curator Paul Schimmel met Frydlender on an Artis trip. “It was shown immediately,” Reinharz said, “the first piece you would see entering the museum.”

Another Artis tour alumnus, Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA PS1 in Queens, New York, and the chief curator at large at MoMA, curated a solo show at MoMA in 2008 for Sigalit Landau. It featured her iconic video installation, DeadSee, in which she is afloat in the Dead Sea on a sinuously uncoiling cluster of watermelons that split, revealing ruby innards, as they dissolve into the aquamarine depths.

Then, in the summer of 2010, the PS1 exhibition “Greater New York,” a showcase of emerging artists, included work by Fried and Tsabar. They were also among 10 artists selected by Artis tour alumna Lily Wei for “The Young Israelis” exhibit that took place around the same time in an L.E.S. gallery and received a major review in The New York Times. Artis’s Web site is an important source for information and news about the Israeli art scene worldwide, offering artists’ biographies and images of their work; reprints of reviews and articles; and listings of lectures, programs and exhibitions beyond and within Israel. (The Art Guides section of the site has definitive listings of museums and galleries throughout the country.)

Recently, while scrolling through the site, I discovered that “Aircraft Carrier,” a monumental survey of Israel’s architectural coming-of-age that was at the 2012 Venice Biennale, will be coming soon to a New York venue. The exhibition includes the work of Assaf Evron, Nira Pereg and Jan Tichy. It will be at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York through April 29.

You can subscribe to Artis’s newsletter to receive e-mail bulletins and to Meislin’s monthly newsletter on her site for updates not only on her gallery shows but on her artists’ exhibitions elsewhere as well as their awards, sales and publications.

And it is always a good idea to keep up with what is happening at Jewish institutions and organizations that tend to be as committed as ever to supporting artists from Israel. On the same day I saw the Chelbin exhibit, I visited the Laurie M. Tisch Gallery at the JCC in Manhattan to see “Exteriors,” a collection of large-size New York cityscapes by Michael Kovner, who is known for his monumental Israeli landscapes. The paintings were displayed around the periphery of the lobby, which was filled with children and their parents, strolling or sitting and gazing up at the painted buildings. We were all actors in Kovner’s extremely pleasant fictional urban outdoor scene.

It was nice in the real outdoors, too, so I walked downtown until I reached the Museum of Arts and Design at Columbus Circle, where I found “Playing with Fire,” an exhibition of contemporary glass that included installations by Israeli designer Ayala Serfaty.

These days, you really don’t have to look hard to find great art from Israel. Sometimes, it even finds you.

Where to See Israeli Art

■“Aircraft Carrier” with Assaf Evron, Nina Pereg and Jan Tichy, Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, NY through April 29.

■“Ori Gersht” at the Gund Gallery at Kenyon College, Gambier, OH through June 23.

■ “Playing with Fire” includes installations by Ayala Serfaty, Museum of Arts and Design, New York, NY, through August 25. Her works, like Morning Glory, can also be seen at Aqua Creations Gallery, New York, NY.

■ “Think First, Shoot Later,” photographs from the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, includes work by Elad Lassry, Chicago, IL, May 18 through November 10.

■ “War Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath” has Micha Bar-Am’s blockbuster The Return from Entebbe, Ben-Gurion Airport, Israel, at the Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles, CA, through June 2.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply