Books

Personality

Books: A Talk With Marvin Fletcher

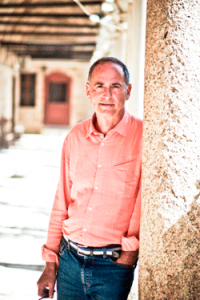

Martin Fletcher is a London-born journalist who has spent his career reporting from the world’s hot spots, including Belgium, Israel, Rwanda, Kosovo and Rhodesia. Initially assigned to cover Israel just before the Yom Kippur War, he has since put down roots there, raising three sons with his Israeli wife, Hagar. After a long career with NBC as its Israel correspondent, he is now semiretired and has written two nonfiction books, Breaking News (St. Martin’s Press) and Walking Israel. (St. Martin’s Press). His novel, The List (St. Martin’s Press), is loosely based on his parents experience as Austrian wartime refugees in England and the prevalent anti-Semitism and xenophobia of the time. He is working on another work of fiction about Jews who remained in Germany after World War II.

Q. What was it like growing up in postwar England?

A. For 60 years, my parents had no English friends, only fellow refugees. My mother could never say the word Jewish without her voice dropping. There was a limited supply of housing and jobs.

Q. How did you get the idea for The List?

A. I had the actual idea and title and part of the story after my father died. He had a list of family members, exactly as in the book, crossing out those who died and the few who did not. He never talked about the list.

Q. How much of the story is based on actual events?

A. The [main] characters and their mannerisms are based on my mother and father. I never intended to use their names, but I had to. I did not have an older sister named Lisa. I have an older brother who was born in 1944. The address of the house is the same, everything that happens in context and background is completely accurate. I researched much more than I needed. For the day [the characters] went to the movies I found out what movie was playing that night.

Q. When you are a journalist writing fiction, is there a lot of pressure to be accurate?

A. It’s a double-edge sword. On the one hand, I felt tremendous freedom, I said ‘I can make it all up, it doesn’t matter because no one will know—it’s a novel.’ On the other hand, I didn’t want to, because the story is very real to me, a very personal story.

Q. Did you experience anti-Semitism as a child in England?

A. I didn’t experience anti-Semitism but I heard a lot of anti-Jewish jokes. In the British context, whether you were black or Asian it would have been exactly the same. Just people being stupid.… I never felt English, I always felt like an outsider. Then again, I don’t really feel Israeli [today] either. The captain of the school football team always said to me, ‘you’re different,’ and at the time I was rather pleased about that.

Q. Has England changed today from those days?

A. It’s still xenophobic and clearly there is anti-Zionism, and Israel is obviously the fig leaf for many anti-Semites. It’s not active anti-Semitism, they’re not going to shoot them, they just don’t like the Jews.

Q. Did your parents talk about their experiences during the war?

A. They spoke about their journey and how they escaped at the last minute. They talked to me about it…like it was reluctantly being dragged out of them. My father would normally just sort of break down in tears. My mother was emotionally closed. She couldn’t talk about it. I was able to interview my mother on camera before she died, which was a stroke of luck.

Q. Did their experiences shape your worldview as a journalist?

A. Perhaps it affected my sense of justice. After writing this book and talking to people about it I came to see, in retrospect, if I was trying to work out why I did what I did [in my career], it was probably the motivating force.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply