Arts

Personality

The Arts: More Than Full Circle

Shortly after sunset on the closing night of Ron Arad’s video installation 720 Degrees, a great many people mill around the sculpture garden of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

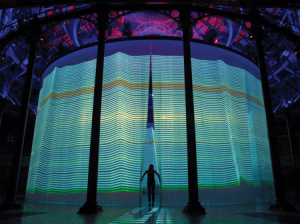

They drag about little metal stools, angling for the best spots to sit. Soon a loop of 11 videos by different artists will begin streaming onto the 26-foot-high movie screen-in-the-round. Made of 5,600 translucent silicone cords, the “screen” shimmies in the darkness—there is a slight breeze—between Robert Indiana’s Ahava sculpture and Anish Kapoor’s Turning the World Upside Down. Right now the screen glows with a ghostly image of…

“Is that the Western Wall?” people ask, gazing in wonder at the vision before them. Indeed it is. The Western Wall-in-the-round.

The inventor of this astonishing work, Israeli-born, London-based superdesigner Arad, is on hand. He is dressed, as usual, in baggy jeans and T-shirt, a casually draped scarf and Cappellone—his signature black wool felt amalgam of bowler, cloche and baseball cap. It was produced by Alessi and sold in a limited edition at New York’s MoMA in conjunction with his 2009 retrospective at the museum.

That exhibition’s title, “No Discipline,” nicely summarizes Arad’s freewheeling, boundary-busting style. His specialty is not having one. 720 Degrees, which closed in Israel last fall, is not his first conceptual piece (though it is his first on an architectural scale). He is equally at home designing, say, a handbag with a battery-powered window so it can be both opaque and transparent, multiple chairs (he has been called “a serial chairer”), a sustainable shopping center or never-been-done-before sunglasses that mold to the face (the line is called “pq” because those letters together look like spectacles; https://pq-eyewear.com). It is the never-been-done-before factor that he relishes, being “surprised in the evening by things you didn’t know existed in the morning.” His studio, he says, is “a bit like a playground.”

How perfect, then, that in 720 Degrees he has provided a playground for museum-goers. The installation debuted as Curtain Call at the Roundhouse theater in London in 2011 and came to Israel as the pièce de résistance of 2012’s Jerusalem Season of Culture (a summer-long festival showcasing the city’s dynamic arts scene). 720 Degrees is not merely interactive but immersive, collaborative and inclusive. You can part the spaghetti-like cords at any point and plunge inside the 60-feet-across enclosure to let the filmed images surround you, then dart outside and circle around the screen. (It’s hard to stay in one place for long.) Arad is clearly pleased, watching people enjoy his work, although, he says, “I’m not normally such a Pollyanna or Mother Teresa.”

In Israel, the installation has also proven its adaptability, becoming part of its surroundings—the museum’s iconic sculptures, the nighttime silhouette of Jerusalem—through the use of the Western Wall as the context for, and holding pattern between, the videos. Jerusalem in all its local color is reflected as well in a spectacular video, Thru Jerusalem, Kutiman’s sound and sight collage of musicians at play amid slices of city life that you can almost smell and taste. (Experience it at www.youtube.com, search for “Kutiman-Thru Jerusalem.”)

720 Degrees could make itself at home in any setting, and Arad has had offers. Moscow might be the next stop, although not immediately. First, he returns to London, where Lolita, his response to Nadja Swarovski’s 2004 invitation to reinvent the chandelier embodying both traditional forms and today’s technology, is starring in the exhibition “Digital Crystal: Swarovski at the Design Museum,” which will run through January 13, 2013. A glamorous spiral of about 2,000 Swarovski crystals concealing over 1,000 LEDs, Lolita receives tweets and texts and displays the messages in lights.

“I travel between London and Israel all the time,” Arad says. (He once said the reason he moved to London was because it’s closer to Israel than Greenwich Village.) “But this is the longest I’ve stayed [in Israel] in 40 years.” His voice is gentle, his English more Israeli than British accented. “Everyone I ever knew here turned up and it became like a memory game. Remember me from kindergarten?”

Arad was born in Tel Aviv in 1951, where his father, Grisha Arad, a photographer, still lives. His mother, artist Esther Peretz Arad, died six years ago. “My father’s 95 now,” Ron Arad notes. “He’s driving, unfortunately. But, what I’m getting at is, he’s photoshopping every day. He works with my mother’s drawings. He’s still working with her. It’s pretty amazing.

After studying architecture at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, Arad got his degree from the Architectural Association in London, where his classmates included Zaha Hadid, who became the first woman to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize. He went to work for an architectural firm but soon quit. In 1981, he opened his own design studio, One Off, and began making furniture to order from industrial materials and found objects. Business was slow until he came upon discarded leather seats from Rover V8 2L cars in a scrap yard. Impressed with their comfort and good looks, he bought a couple and mounted them on metal frames with Kee Klamps. Jean-Paul Gaultier bought them. Recalling this seminal moment, Arad mentions that he and Gaultier “and Barbra Streisand!” share a birthday—April 24.

Major commissions and acclaim followed, along with its inevitable opposite (“Only Nelson Mandela doesn’t get criticized,” Arad once observed). In 1987, Arad’s work was displayed in “Nouvelles Tendences” (New Trends), the 10th-anniversary exhibition of the Centre Pompidou in Paris—and, that same year, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Design Museum in Osaka and the Tel Aviv Museum. He was making art history—his success helped pioneer the rise of the concept of design as art.

Arad has designed for, among other trail-blazing firms, Vitra, Kartell and Moroso. He has created mass-produced designs, limited-edition runs of furniture and accessories and one-of-a-kind pieces for collectors who pay five or six figures for furnishings capable of going one on one with the art on their walls. Some of his designs can be the art on your wall—Bookworm, for instance, his best-selling spiraling bookcase that comes in three sizes (https://kartellstorela.com). Or the wall-climbing mirrored tables of Paved with Good Intentions, his installation for Design Miami in 2005.

His furnishings can double as sculpture—for example the aluminum and steel PizzaKobra lamp; it unwinds from a flat, round coil into a sinuous snake with six LED “eyes” that can be twisted to shed light in any direction. Some of Arad’s mass-produced pieces spawn limited-edition offspring—and vice versa. Otherwise, he avoids repetition. “I like to fly from one interesting thing to another interesting thing,” he says. His style, however, is unmistakable—organic, with lots of curves—as is his love of coaxing maximum visual drama from the newest materials (some quite humble) and the latest technology.

(“It’s one of the layers,” he says.) He loves playing with words, too. All his works have carefully considered titles. Consider just a few: The Big Easy (your dad’s armchair much inflated and in stainless steel); This Mortal Coil (of the Bookworm family); the Pappardelle chair (a woven steel blow-up of that broad, flat pasta); the Well Tempered chair (followed by the Bad Tempered chair); the Little Albert, honoring the Victoria and Albert and included in a recent New York Times home section article that tried to predict which of today’s design icons would become the Eames chairs of 2050.

Sometimes, words become a design element. For instance, a quote from artist Marcel Duchamp—“There is no solution because there is no problem”—appears in French and English on the transparent version of the Oh-Void chair. And words can engender a work. 720 Degrees began, explains Arad, “as a wisecrack. It was for the Roundhouse, which is big and round. So I said, ‘Let’s do something big and round.’”

And then? “I followed my curiosity. Next to boredom, curiosity is the mother of invention.”

Arad did not return to architecture until 1994, when he entered a competition to design the Tel Aviv Opera House public spaces “and they made a mistake and gave it to me.” The opera’s foyer is echt Arad; the curving, undulating shapes articulating the staircase, bookshop and café open up and dramatize the entire space, and the interplay of bronze and concrete provides glamour and magic. Among the architectural feats that followed are the DuoMo Hotel in Rimini, Italy; Médiacité shopping center in Liège, Belgium; and the Design Museum Holon, near Tel Aviv, Israel’s first museum devoted entirely to design, which opened in 2010.

The design museum—buoyed aesthetically and structurally by a dashing wrap-around shell of five Corten steel bands in varying shades of rust—“attained iconic status before a single exhibition…opened,” according to the Ha’aretz daily. In May 2013, Arad will have an exhibition there, the focus of which is “top secret,” Arad says.

Arad has another Israeli project under way, a 72-story office block. “And it’s not a phallic tower. It will be the biggest building in Tel Aviv. Until there’s a bigger one.” He is also working on the renovation of the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C.

On its final night in israel, 720 Degrees drew an audience of over 2,000. In total, 30,040 people experienced it. The mood, at a gathering inside the installation for the team from the Israel Museum, the Roundhouse theater and the Jerusalem Season of Culture—all those who helped make this event happen—is one of elation, tinged with a bit of sadness.

“We’re overwhelmed,” says Itay Mautner, artistic director of the Season of Culture. At one point, members of the team plunk knock-off Cappellones on their heads, toast Arad, then toss the caps in the air and cheer.

And there is a brief press conference conducted by Arad and Mautner that ends with Arad asking, “You want to see the best image of them all?”

“You want me to put it on?” asks Mautner. “The best image?”

“Yeah, put it on.”

“You ready, Ron? The best image. Shalosh, shtayim, ehat.”

All the lights go out.

“Here it is. Look at it,” Arad says, gesturing at the panoramic nighttime silhouette of Jerusalem that surrounds the group.

“Jerusalem,” says Mautner. “And the moon. Nice work, Ron! Ron Arad: The Moon.”

It is hard to imagine that within a few hours 720 Degrees, down to the last silicone cord, will be packed up in two crates and on the way to the ship that will take it to England. From there—who knows? It may be coming to a museum near you.

Elin Schoen Brockman is currently working on a novel. Her Web site is www.elinschoenbrockman.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply