American View

Personality

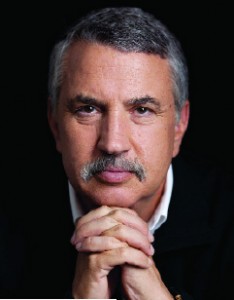

Interview: Thomas L. Friedman

September 28. Thomas L. Friedman is an author, New York Times columnist and three-time Pulitzer Prize winner, broadcast news commentator and documentary host. He has written extensively on foreign affairs, terrorism, environmental issues, globalization and trade.

September 28. Thomas L. Friedman is an author, New York Times columnist and three-time Pulitzer Prize winner, broadcast news commentator and documentary host. He has written extensively on foreign affairs, terrorism, environmental issues, globalization and trade.

Q. When and where does the red line arrive regarding Iranian nuclear weaponization?

A. Clearly America and Israel have different red lines because they have different strategic capabilities. America can afford to wait longer because we have stealth bombers. We can penetrate Iran’s defenses at scale with bunker buster bombs that Israel doesn’t have, any time we want. Israel cannot. Israel can’t deliver as much of a punch so it has to consider when what Iran has approaches a level of invulnerability and carefully weigh the scale and impact it can have.

Q. What will the line in the sand be for Americans?

A. It will be when the world has put on the table what we consider to be the bottom line and says, “Take it or leave it.” We will say something like, “You say you need to do nuclear reprocessing for your civilian electricity and medical testing. Here’s the deal, we will let you enrich up to 5 percent—far below weapons-grade—under the most stringent international observation. Everything else you have to give up.…”

Q. And Israel is to sit back stoically as this plays out?

A. I don’t know. That is an Israeli calculation and I respect how difficult it is.

Q. Will the final outcome in Syria—whatever it may be—bring a strategic improvement for Israel?

A. There is no question that changing the political balance from an Alawite-Shi’ite pro-Iranian regime ruling over a Sunni Muslim majority to a Sunni Muslim majority rule that is hostile to Iran would, in theory, be a strategic win for the West, for America and, I believe, for Israel. The problem is getting from here to there likely will be accompanied by tremendous instability, a possible loss of control over chemical weapons, the possible emergence of Al-Qaeda or other foreign forces [in Syria] with safe havens, the possible Turkish invasion of northern Syria to clamp down on the pro-PKK Kurds there, spillover into Jordan, tremendous human pressure on Jordan’s and Lebanon’s infrastructure by refugees—that is minefield of possibilities that might be part of the scenario.

Q. Do you think Jews will continue to vote Democratic in the upcoming election?

A. The headline here is that 70 to 75 percent [of] Jews vote Democratic. And that difference between 70 and 75, or 69 and 76 percent, depends on the candidate and the context. The bottom line is not going to change; roughly 70 percent of American Jewish voters are going for Barack Obama. They do so because they are committed to the Democratic Party, to its liberal agenda, particularly on social issues, and some believe that the president really has done a good job and will do so in the future.

Q. How central is Israel as an issue for Jews?

A. You have two things going on. Some people are voting their pocketbook, and it’s not all about Israel. And then you have the Israel question. I think the case could be made on a pure intelligence-cooperation, weapons-transferred basis that this leader is more pro-Israel than any American president since Richard Nixon…during the 1973 war. On substantive matters of life and death for Israel, the Obama record impresses. I interviewed Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak recently and he expressed this at a public event. I asked him specifically, Is Barack Obama a friend of Israel? And his answer was: Not only a friend but, in strategic terms, an incredibly important friend.

Q. Yet President Obama shows no passion for Israel?

A. It was a mistake for him not to have gone to Israel some time in the last four years. I understand Israelis’ insecurities, especially now with the Middle East crumbling around it. It never hurts to put an arm around a friend’s shoulder. But this is a president who doesn’t emote, period. Not toward journalists, not toward fellow Democrats, not toward donors. This is one of the big complaints about Obama. So to Israelis and Jews I say welcome to the crowd…. [But] in terms of substance, life and death things that matter, this is a president who has had Israel’s back.

Q. Do you agree that the hopes engendered by the Arab Spring are turning into an Islamist nightmare?

A. For 50 years, Israel enjoyed a kind of imposed stability surrounding it—a stability that comes from kings and dictators. [Now] a new order is going to be born. I think the creation of that new order is going to [last] for the rest of our lives. It’s going to be a big challenge. Those dictators were good for Israel—there was someone to answer the phone, someone to keep the bad guys down internally—but for the vast majority of their people they were terrible. Pining away for the return of [Hosni] Mubarak and [Bashir] Assad is a fool’s errand…. But the transition is going to be extremely rocky.

Q. Are you surprised at how quickly the Muslim hard-liners ascended in Egypt and other Middle East countries?

A. Because the fundamentalists were the only political forces that were organized underground, there is no surprise that they are the first to emerge—the Muslim Brotherhood, and others like them. Iran is the story of political Islam in power with oil. Saudi Arabia is the story of another kind of political Islam in power with oil. Egypt will be the first example at scale of political Islam in power without oil. The Muslim Brotherhood could take Egypt the Taliban route or the more cautious Turkish route…. It’s an incredibly dynamic, complicated transition in which we Americans and Israel need to draw red lines where necessary, building bridges where possible….

Q. What do you make of Israel’s relatively warm reception during the visit of Russian President Vladimir Putin?

A. It was a very rational Israeli response. Israel’s going to find itself on the other side of Russia in a lot of other stories. But if Putin is ready to work with Israel occasionally—this is a guy and a country who know a lot about what is going on inside Syria—they will have a certain amount of say about what evolves there. Israel should want to have a serious relationship with that country.

Q. You have stated that the West Bank is a demographic time bomb that will eventually wreck Israel’s Jewish and democratic character. Is this still your position?

A. There are other reasons. One of them is that people don’t like to be occupied by other people. Jews don’t like being occupied, Arabs don’t like being occupied, Kurds don’t like to be occupied. Lebanese don’t like being occupied by Syrians, Iraqis don’t like being occupied by Americans. Occupations are corrosive. They lead to corruption—moral, strategic and economic. Principle number two is in the long-term impact. Whether it is in 5 years or 10 years, the demographic numbers aren’t that far off. Israel will face a real moral and political challenge of maintaining itself as a healthy Jewish democracy if it permanently absorbs the West Bank.

Q. If, as many say, Israel has no partner for peace, how can it make territorial concessions for an agreement that the other side will not enforce?

A. I don’t think we have a Palestinian leadership that represents a Palestinian consensus, even if you do a land swap [with] all the Clinton parameters, give them the Arab areas of East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital. So I do not know if and how it will work. I do know one thing: Given the alternative, given the threat down the road to Israel, it is in Israel’s overwhelming interest to test, test, retest, test again and call back for the 15th time to see if there is a chance to make it work. My criticism isn’t “Why haven’t you surrendered?” I have no illusions about Israel’s dangerous neighborhood…. But I also have no illusion that “the settlements aren’t the problem.” Or, “We tried that once, three years ago and it didn’t work.” If you will pardon me, that’s not serious. My criticism is that a country with this much energy, this much power relative to its enemies…and this much ingenuity isn’t using…those [assets] every day to look for either negotiated or unilateral ways to free itself from this burden.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply