Books

Feature

Fiction

Fiction: Poetic License

There was no traffic along Ardmore Road, but Sarah Rabinowitz carefully signaled the turn onto Cornus Plaza, slowed and double-checked to make sure Irving Clurman wasn’t in the street. Irving had begun to wander when his wife wasn’t looking. Then she pulled into her driveway and, seeing Bea Bernstein begin her mincing walk across the lawn separating their condos, cut her short with a wave at once both friendly and dismissive.

“See you later!” Sarah called. Bea shrank back toward her own yard. Sarah found her house keys, kissed the mezuza on the front door and sighed with relief as she entered her home.

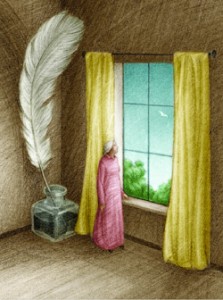

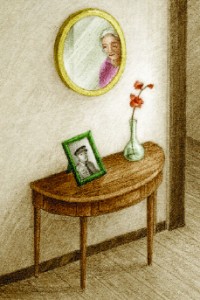

“Hi, Herbie! I survived the turnpike, but it’s getting harder every day,” she greeted the photograph of a handsome young soldier in his World War II uniform guarding the bookcase in the entrance hallway. “He looks like a model!” Bea had said on first seeing it.

She had four telephone messages. One was from her doctor’s office, confirming an upcoming appointment. “The ’pike again,” she sighed. The second was from Bette Markowitz: “Sarah, call me! I have such a funny story about that ridiculous Bea!” The third message was from the Bernstein woman herself. “Bea Bernstein from next door,” she said with a whine. “Can you come for tea later today?” Sarah deleted the message.

The fourth call was important. The caller was young and sounded even younger as her tone shifted from belligerence to confusion to something Sarah could not identify. “She’s vulnerable,” Sarah realized, and was pleased. She had so hoped she had not chosen one of those arrogant, know-it-all young women.

“This is Barrie Jamison. You left me a message about an award…for my…my poetry. I never heard of The Herbert and Sarah Rabinowitz Award for Undergraduate Poetry. I can’t find anything about it online.” Good for her, Sarah thought. Defensive, aggressive, anxious, shy—and smart, too. And she writes good poetry. I liked what I read in the college literary magazine. I’ll invite her for lunch next week.

The phone rang and Sarah groaned inwardly when she heard Bea’s voice. Never pretty, never rich, never married—without a husband, living or dead, children or grandchildren to boast or complain about—Bea had grown from a plain, awkward girl into a plain, awkward old woman who clung to fragments of other women’s lives. But, unlike the rest of the women in the retirement community, Sarah could not simply ignore her. Much of this, she knew, had to do with Herbie. “See what you rescued me from, sweetheart?” she said to the photograph on the coffee table, a smudged snapshot of a middle-aged man. “Do you think they would have been kinder to me?”

“Can’t make tea today. Maybe tomorrow.”

“Can’t make tea today. Maybe tomorrow.”

She felt the beginning of a headache. Sarah had hoped her move to the retirement community six years before would have eased her tendency toward tension headaches. “Shady Acres,” her nephew dismissed it during his only visit, but Sarah took great pleasure in furnishing her small condo and organizing a tiny flower garden. Her pension plus Social Security provided enough to get by on. It was just that—well, she hated to admit it, but some of the women in the community drove her up the wall. Cliquey, bossy and interfering, they were the same types she had disliked since high school. And it wasn’t just Bea Bernstein. She could deal with Bea. It was women like Annie Clurman, who introduced herself the day after Sarah moved in, explaining that she and her husband lived in the large unit across the street. Three bedrooms, she stressed.

“After the house in Short Hills, we simply couldn’t trade down. Are you married, dear? Or—”

“Widowed,” Sarah said. “Herbie died 10 years ago. Pancreatic cancer.”

“It’s so hard for widows,” Annie said. “Thank God my Irving is well. He was in publishing.” Probably had a newspaper delivery route, Sarah thought, but smiled sweetly. “Our son is a physician. With the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. They live in Wellesley, Massachusetts. It is very upscale. Do you have children?”

“One daughter. In California.”

“Grandchildren? After all, your children are your children, but I always say you’re nothing until you have grandchildren. Did you and Sammy—”

“Herbie.”

“Do you have grandchildren, dear?”

Which was how Sarah’s granddaughter was born.

They met at a coffee shop on George Street, the drag that divided the main campus from the women’s studies school. Sarah, who had attended evening classes at Hunter College’s urban campus in New York for years, loved traditional college towns.

The girl was no more than 19, and a young 19 at that, still protected by baby fat, skin shining from late adolescent oil and acne. Her eyes were mature, though, and guarded, and Sarah wondered why her lids had come down so early, a sharp defense between a vulnerable soul and the real world.

“About this award,” the girl said.

“The Herbert and Sarah Rabinowitz Award for Undergraduate Poetry. My late husband and I both loved poetry.”

“Could I ask, I mean, why did you choose my poems? It’s not like I applied.”

Sarah gave the practiced response. “It’s still a new award. Next year, perhaps, we’ll institute a formal application process. This year, well, I saw some of your poems in the student literary magazine and was very taken with them.”

“My roommate says it’s a hoax.” Barrie raised her eyes and looked defensively at Sarah. “She Googled the…the…”

“The Rabinowitz Prize.”

“She says it doesn’t exist, that it’s a scam. She says I shouldn’t trust you, you’re a swindler and it’s going to cost me money.”

“Oh, the award is real all right. It’s not well known because this is our first year and, frankly, I don’t understand anything about publicity. But it is not going to cost you anything. In fact,” Sarah opened her handbag, “there is a cash prize of $250. And a certificate.”

She handed the dumbfounded girl an envelope. “I remember what it was like to be a student. Extra money is always helpful. Oh, there is one thing more.”

“What’s that?” Suspicion was back in the girl’s eyes.

“A lot of young women lose their voices. I hope you keep writing. You’ve been published in the college literary magazine…”

“And in my hometown newspaper,” Barrie interrupted. “And, of course, now there’s the Rabinowitz Prize.”

They smiled at each other.

“I hoped—well, I’m no expert in poetry, but I hoped we could meet occasionally to discuss your work,” Sarah said.

“And other poets. I’m very fond of Robert Frost.”

“I am, too!” the girl said eagerly. “My professors don’t like him. They say he’s outdated and trite. But I think he’s wonderful!”

They agreed to meet for lunch the following month to talk more about poetry. Sarah said it would be her treat, and her pleasure. “Mine, too,” Barrie said.

There were two messages from Annie Clurman, both about Bea Bernstein. “You must see that getup she’s wearing today. It went out of style in 1985.” Maybe that’s all she can afford, honey, Sarah thought. Bea worked as a salesgirl at Macy’s for 40 years. How much money can she have put aside for her old age? And she doesn’t have those perfect children and grandchildren to boast about, like yours. The ones who never visit you.

She wondered if she should urge Barrie to save some of the prize money, to open a bank account against the rainy days that were sure to come. But the world of 19 should only care about sunny skies and, in the end, Sarah did not warn her. They talked about other things at lunch the next month and the months after that. Barrie shared her poetry, which Sarah thought overly influenced by the pastoral. She did not voice her opinion, although she did ask why someone who had grown up in a suburb like South Orange, New Jersey, wrote so movingly about milking.

“Suppressed maternal instinct?” Barrie giggled. She was taking psychology that semester. “I don’t know much about cows, but then, I don’t know much about love either.”

“No boyfriend?”

“No. And I’m a sophomore already.”

“I thought things had changed for women.”

Barrie laughed. “I don’t know. I mean, everyone talks about careers, and the professors encourage us and all, but then it’s Saturday night and it’s all ‘Who’s your boyfriend?’ and how great the sex is. And if you don’t have a partner, well—I mean, they’re nice enough I guess, but—I can’t explain it. They’re polite and all, but you’re not really one of them.”

“I understand.”

“How did you meet your husband?” Barrie asked.

“It’s funny. We met in a framing shop in Brooklyn. We just…met one morning. He was a lovely man, Herbie.” She coughed. “I was almost 40. So don’t give up hope.”

“Do you miss him?”

“Of course. But I’ve been a widow for a long time. And in some ways, he’s as real to me as he ever was.”

The following month, Barrie shared a love poem Sarah thought awkward, lacking the girl’s usual lyrical flow. The girl sensed her criticism. “You don’t like it,” she said.

“Well,” Sarah said carefully, “it’s not bad. It’s just—”

“It’s just that I don’t know anything about love! It’s like everyone has someone but me!” Changing the subject abruptly, she asked, “Do you have children?”

“Yes. A daughter. In California. A pity, but we’re not very close.”

“Grandchildren?”

“No. None. A disappointment, but you can’t have everything in life.”

“Tell me about it,” Barrie said.

“You don’t talk much about your granddaughter, Sarah,” Myra Schwartz said. The women were having tea in Annie’s condo. Bea, who had tagged along with Sarah, cackled. Sarah smiled, eager to avoid any danger.

“She’s a lovely girl,” Sarah said. “She’s over at the college.”

“Do you see her often?” Bea asked, cunningly.

“About once a month.”

“That’s all? And her so close by?”

“You wouldn’t understand, Bea,” Myra said. “You haven’t been married.”

Sarah let Bea suffer her embarrassment alone and studied the plain gold band on her left ring finger. I have that appointment with Dr. Marcus next week, she thought. The turnpike again. What a pain.

As things turned out, she was on the highway twice that week, the second time to meet with her attorney. “I changed the will,” she told the photograph on the night table. “Most of what’s left is for the hospital in Haifa. And I added the poetry award.”

Sarah looked forward to her monthly lunches with Barrie and was pleased the girl seemed to enjoy them too. It wasn’t really like having a granddaughter, she thought. There’s no connection of birth and blood, no shared history. It’s more like having a dear friend of a different generation. They were discussing Yeats one afternoon when Sarah saw Annie Clurman bearing down on them. Please let her go away, she prayed.

“What a surprise!” Annie said. “Is this your granddaughter? How nice to meet you, dear. You should really visit your grandmother more often, being at college so close by.”

“Please,” Sarah said. “This isn’t the time for advice.” Annie smiled coldly and walked away.

“Why did she call me your granddaughter?” Barrie said. “You said you don’t have grandchildren.”

“Oh, she just got confused,” Sarah said, coughing slightly. “At our age—”

“No, she really thought I was your granddaughter. Why did you tell her that?”

“I’m so sorry. It’s just that—” Sarah was caught up in a paroxysm of coughing.

“But you don’t have a granddaughter. And you never talk about your daughter. Do you even have a daughter?”

I was so close, Sarah thought. Why now?

Barrie glared at her. “I knew this was a scam! You and Herbie never had children, did you?” Sarah blushed and nodded. “You made it up. What kind of game are you playing? Don’t tell me you made up Herbie, too.” Then, her eyes widening, she said, “There’s no Herbie, is there? Why, you’ve never even been married, have you?”

The shot in the dark hit home. Sarah wanted to flee the restaurant. Then she looked at Barrie. An expression of delight had spread across the girl’s plain features.

“You old fraud!” Barrie said. “You invented Herbie!”

“Yes. You wouldn’t understand—”

“Wouldn’t I? I live in a dorm with other girls. I know what it’s like to be the one without a boyfriend.”

“It’s different today,” Sarah said. “You can have a career. You can travel. You can have a baby even if you’re not married. We had nothing. And when I retired and moved here—”

“Into the dormitory for retired ladies.”

“Yes, Shady Acres. I wasn’t going to let myself become the woman all the other women mock, the women with less than the least of them.”

Sarah died of lung cancer in March. The funeral home was crowded with neighbors from the retirement community.

“Of course, they’ll be there,” she said to Barrie during the girl’s last visit to the hospice. “What else do they have to do before the early-bird special?”

The Sarah and Herbert (“wink, wink,” Barrie said) Rabinowitz Award would continue through a small grant in Sarah’s will, with Barrie as administrator. The girl didn’t yet know there was also money in the will for her to use for a trip to Europe, graduate school or a fancy wedding. “One other thing,” Sarah said. “There’s something I’d like you to give my friend Bea before I pass.”

Sarah’s nephew was sorry, but he was leaving for Barbados and couldn’t make the funeral. Barrie sat alone in the family pew. “That’s the granddaughter,” whispered Annie to Myra. “I met her once. Shy. She’s over at the college. Must not have a boyfriend, otherwise he would be here too. Kids today. I told her she should pay more attention to her grandmother.”

“And the daughter?” Myra said. “Where is she? Lives in California, but you’d think she’d turn up for her own mother’s funeral. Maybe that’s why Sarah never talked much about her. It’s like she didn’t exist. It was always Herbie, Herbie, Herbie. And the granddaughter, of course. Chubby, isn’t she, the girl?”

The rabbi organized the pages of the eulogy. Sarah Markowitz—no, Rabinowitz—woman of valor. He did not notice that Bea Bernstein was among the last to arrive. Bea was walking proudly and sedately. And she was wearing a mink coat.

“Bea! We’re over here!” Annie Clur-man called. Bea sat down with the women from the community. “Magnificent!” Annie said, stroking the fur, not recognizing Sarah’s mink, the one she had asked Barrie to give the Bernstein woman before she died. The rabbi began to intone a prayer.

“Bea, we’re going for coffee after the service,” Annie whispered. “Why don’t you join us?”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Gail Lipsitz says

Great story! Can you please provide some biographical information on the author, Kathyrn Ruth Bloom? I cannot find anything about her online.

Thank you.

Gail Lipsitz

Hadassah member