Hadassah

Feature

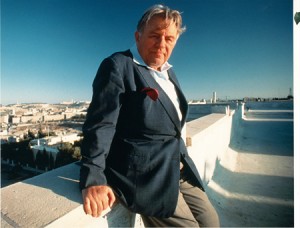

Old Friends: Two Zionists Grow Up Together

Hadassah and I were born within months of each other on opposite sides of the globe. It, of course, was as unaware of the infant struggling into life in pre-World War I Vienna as I was of the group of determined women in New York who sent two nurses to open a health station in Jerusalem—and launched a medical phenomenon.

I discovered them sooner than they found out about me. By the time I reached Palestine 22 years later, Hadassah had already thrown a network of health stations across the country, one of them within reach of the swampy Kinneret shore where I went to build a new kibbutz.

It was not until the late 1940s and early 1950s, when I spent four years in the United States with the Hagana and with our embassy in Washington, that I made contact with Hadassah on its home ground. I then began to understand the single-minded vigor of these women and their involvement in the health and social services of a country 6,000 miles away.

Five years later, in the mid-’50s, the alliance between us began with a dramatic drumroll. I was chairing the Israel Government Tourist Corporation, responsible for Israel’s tourist industry. Around 45,000 tourists were expected that year—a small figure compared with the numbers who come today, but then as now an important injection into the country’s economy.

But with the 1956 Sinai Campaign, the United States banned travel to the Middle East and tourism zoomed down to zero. The King David Hotel in Jerusalem closed its doors. Éveryone who depended on the tourist trade faced bankruptcy.

I looked around to see what could be done and almost naturally I turned to Hadassah. I asked Hadassah to schedule a mission in Jerusalem and to request State Department permission for its members to attend. Hadassah agreed and marched into action. It succeeded: The tourist blockade was broken and Israel, particularly Jerusalem, was turned into the international convention center it is today.

With this precedent, I was not surprised 35 years later when Hadassah moved part of its 1991 midwinter convention to Jerusalem, arriving in January even as Saddam Hussein’s Scuds were falling. It was a gesture of solidarity and cheer that I and other Jerusalemites appreciated—another link in the bond between Hadassah and Jerusalem, and between Hadassah and myself.

As we both turn 80, I’ve been thinking about why that bond has endured. Part of the reason is that we both hold Jerusalem at the center of our aspirations. It is no mere chance that Hadassah opened its first health station in this most special of cities or built its hospitals and medical schools here, its community health center, its technical college and vocational guidance center, with all they have contributed to the city and its people.

But more than this, I believe that Hadassah and I follow many of the same ideals. We are both pragmatists. We start with the possible. For me that has meant paving roads, laying sewage pipes, improving garbage collection, building theaters, encouraging commerce, reconstructing ancient sites. In short, proving that the possible means keeping Jerusalem from becoming another Belfast—even if heavenly peace and harmony may at times elude us.

For Hadassah, the possible has meant much the same: providing the best and most advanced in preventive and curative health care and in medical research and education. By establishing centers of medical excellence in Jerusalem, Hadassah contributes not only to the health of citizens—and to the modern city’s prestige—but also makes a vital and massive contribution to Jerusalem’s economy, providing thousands of jobs. And in a city where employment is strongly biased toward academia and public service, job- and income-generating concerns are important.

Another vital and potentially explosive area where Hadassah and I have always seen eye to eye is equality. Hadassah—in Jerusalem since 1912—has since the first day taken in all comers, regardless of how and where they worship. I’m a comparative latecomer on the scene: I have been Jerusalem’s mayor only since 1965. But a cornerstone of my administration has been and always will be equal public and municipal services for all.

That both Hadassah and I have credibility among all sectors of the population is borne out by what happened during the 1987 intifada. Palestinian Arabs continued seeking help at Hadassah’s hospitals throughout the conflict, even in its worst moments. And despite a large Arab minority in Jerusalem, there was never a breakdown of order in the city.

Hadassah has done the seemingly impossible so often that it is now virtually expected of the organization. It has raised phenomenal sums of money to build and maintain high-technology hospitals that practice advanced medicine. It has solved practical and administrative, political and bureaucratic problems because the objective was so clear that obstacles were seen as there only to be overcome.

I’ll never forget how Hadassah responded to my phone call in June 1967. It was in the heady week of the Six-Day War and the battle for Jerusalem had just been won. Somewhat euphoric myself, I picked up the phone and called Kalman Mann, then director general of the Hadassah–Hebrew University Medical Center.

“If you want your hospital, come and get it,” I said. And come they did. First Dr. Mann and his colleagues came, renewing acquaintance with the old abandoned hospital building on Mount Scopus. And within weeks, Hadassah had undertaken a massive fundraising drive to rebuild its first hospital even though it had been replaced six years earlier with the then- 400-bed Ein Kerem facility.

A good reputation need not be a bad thing, of course. Both Hadassah and I have used our reputations to enlarge what we can do. We both went international. I established the Jerusalem Foundation: Since the world seems to feel it is a partner in running our city, I decided to enlist the world’s help in solving the city’s special problems. Through the foundation, people worldwide—Jews and non-Jews—contribute to specific projects and have greatly enriched this city.

Hadassah too knew that its medical center—serving the city, the nation and, unofficially, many people from surrounding nations as well—is of universal concern. And so in 1983, Hadassah invited in the world, forming the Hadassah Medical Relief Association, now called Hadassah International, to channel the support of men and women, Jewish and non-Jewish, across the globe.

At 80 years old, Hadassah is visibly full of the vigor that our sages say is the due of an octogenarian—its hospitals are flourishing.

As always, Hadassah remains flexible and responsive. Today, Soviet and Ethiopian immigrants need help and all Hadassah’s multifaceted institutions are involved. Tomorrow? I do not know as yet nor do they, but I have no doubt that as soon as they do they’ll be sure to play their part.

Comedian Jack Benny once said “Age is strictly a case of mind over matter.” If you don’t mind, I recognize that 80 years old in a lifespan means one is no longer a youngster. I’m glad that for Hadassah at least, age is scarcely relevant.

Teddy Kollek was mayor of Jerusalem for 28 years. He died at age 95 in 2007. This article originally appeared in the March 1992 issue of Hadassah Magazine.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply