Hadassah

Feature

Health + Medicine

Feature

Medicine: A Dream Becomes Reality

Jerusalemites are a conservative bunch. The now popular Knesset building was disliked for a decade following its 1966 inauguration, and the jury is still out on Santiago Calatrava’s four-year-old Bridge of Strings at the city entrance.

This conservatism, however, was nowhere in sight when the new inpatient center at the Hadassah–Hebrew University Medical Center in Ein Kerem opened on March 19. The $363-million Sarah Wetsman Davidson Hospital Tower was instantly popular.

“It is a paradise,” says Gila Ben Shushan, head nurse of orthopedics, whose department moved into the tower in April. “Even though we are as busy as ever here, our patients are visibly less stressed and seemingly experience less pain.”

One of those patients is isaac galanti, whose three previous hospitalizations were in Hadassah’s original inpatient building, opened in the 1950s. “You cannot compare the two,” he says. “It’s not only the facilities that are different, but also the medical staff. They’re more relaxed, which makes me more relaxed.”

The tower is named for Detroit businessman Bill Davidson’s grandmother; he gave $75 million to help build the tower. The gift came with an unusual backstory. In 1921, Davidson’s grandfather helped purchase an ambulance for the Zionist Medical Corps, which was partially run by Hadassah. Sarah Wetsman Davidson started Hadassah’s Detroit chapter. Sadly, Bill Davidson did not live to see the tower completed. He died in 2009.

“The place is like a five-star hotel,” says Zev Kesselman, who has been part of Hadassah’s computer department for over 30 years. He came to see the tower, which stands on the site of the rectangular building in which he once worked.

The hotel comparison is striking, and it is no coincidence. Twenty-first-century hospitals relate to the patient as a consumer and are beginning to incorporate personalized amenities—among them, room service and designated spaces for family and visitors. “It is now understood that the hospital environment actively contributes to the well-being and recovery of patients,” says Dr. Ehud S. Kokia, director general of the Hadassah Medical Organization.

Hospitals have come a long way from the un-sanitary and crowded church-run sick houses of the Middle Ages. Their evolution into bleak, sterile institutions during the past 200 years (the model to which most of the 17,000-plus hospitals worldwide conform) is, however, far from ideal.

“Hospitals should be living spaces for patients, not warehouses for the sick, where design is dictated by the assembly line,” explains tower architect Arthur Spector of Jerusalem-based Spector Amisar Architects. “A healthy hospital environment is a community in which the patient is not an object, but the focus.”

While design cannot replace medical care or restore the patient’s autonomy, it can help reduce stress and counter the sense of helplessness. Hospitals are being transformed, and Hadassah’s inpatient tower both reflects what has been learned and pushes the boundaries of knowledge of the healing environment.

The blueprint for the tower emerged from hundreds of meetings between architects and Hadassah’s administrative, medical and nursing staff, many of whom toured medical facilities worldwide. “I made a point of asking people working in the centers I visited what they thought was wrong with the design as well as what was right,” says Dr. Charles Weissman, head of Hadassah’s anesthesiology and critical care medicine department, tasked with helping plan the tower’s operating rooms and intensive care units.

“The most complex part of a project like this is usually interfacing with the client,” says Spector, who coordinated the team of 25 architects and planners from Spector Amisar and Texas-based architects HKS. “But in this project, the client was integral.”

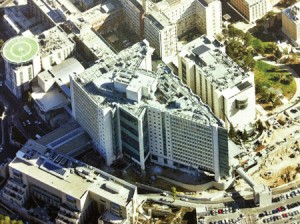

The result is a 19-story building, 5 of them belowground. “It has to be tall,” explains Spector, “because all inpatient rooms must be within [164 feet] of the trauma ORs, and once you pile on more functions, the building rises.” But this doesn’t mean it need be square or characterless.

The tower comprises three massive intersecting triangles. The central triangle on each level, donated by Iranian-born Hadassah member Katherine Merage, is for support services, step-down units, waiting areas, conference rooms, elevators and healing gardens. The triangles to its east and west house inpatient departments. They are the gift of Judy and Sidney Swartz—the west wing in memory of Judy’s parents, Natalie R. and Allan J. Hyde, and the east in memory of Sidney’s parents, Nathan and Ruth Swartz. The tower’s total floor space—equivalent to four soccer fields—doubles the size of the original hospital. With sense of place important in reducing patient stress, signage abounds, detailing wing, floor and department information.

The tower’s entrance is the new main entrance to the medical center. The 25,000 people who come to Hadassah each day by bus, car (a 1,000-space parking lot is across the road) and, eventually, light rail will disembark directly outside it to enter an airy glass atrium rising three stories high. Trees grow inside, and it is filled with sunlight, filtered by a giant window blind across its glass roof.

“This entrance atrium, the David and Fela Shapell Family Gateway to Health, is the hub that channels all hospital traffic,” says Miriam Beinash of Hadassah’s development, donors and events department. “It gives direct access to admissions, emergency medicine, the delivery rooms, Children’s Pavilion and Chagall windows [at the Abbell Synagogue] as well as to the Ishpro Mall and Hadassah Hotel. In the atrium itself are the information desk, gift shop and business center.” In addition, the atrium will feature the Albert and Ethel Herzstein Heritage Center, an interactive exhibition space dedicated to the telling of Hadassah’s story.

Admissions, to the left of the atrium, expresses the new workflow and design ethos. “Doctors now come to patients, rather than sending patients to the different departments,” says Beinash. “And all basic biochemical tests are performed in a large area adjacent to admissions.”

Included in that area is the two-story Moshe Saba Masri Synagogue, which is still being built; a metal bas-relief Holocaust memorial; and the luxuriant shrubbery of the Barbara and Jack Kay Garden, which flourishes inside the building along the glass wall of the central triangle and through to the elevator bank. The tower is serviced by three escalators and 20 silent elevators that, like everything else in the building, are state of the art. Six elevators are for the public; three of them are glass-encased, their shafts along the tower’s glass wall. The others are for patients, medical equipment and food.

On the medical floors, too, the atmosphere is relaxed and noninstitutional. Corridors are wide, their clean lines unbroken by wall decorations. Colors have been carefully chosen: blue, calming and serene, mixes with beige and brown, associated with friendship, stability and security.

Leading off the corridors are the patient rooms, where the hotel-like feeling resurges. A third of the tower’s 500 inpatient beds are in single rooms, the remainder in doubles. The furniture is wood and, with all inpatient rooms hugging the exterior of the building, every bed has a window. Next to each bed is a recliner where relatives can spend the night. Every room has a safe, closet, Shabbat light, en suite bathroom and flat-screen television and communication system with Internet access, on which patients can surf, choose meals and contact their doctors.

“When we go to a patient, we are no longer grabbed by four or five others in the room who suddenly remember they need something,” says orthopedic nurse Ben Shushan. “We can listen to him or her and explain our answer. We can practice real nursing in the way we want to.”

“With five in the room and all their visitors, it was never quiet for a second,” says Galanti. “The reduction in noise level and the privacy are incredibly welcome.”

Galanti is bedridden, but for mobile patients and their families, the day lounges are breathtaking, their glass walls framing the spectacular view across the Judean Hills. With grouped chairs and tables, hot and cold drinks and a small kitchenette, the day lounges resemble cafés.

If a coffeehouse atmosphere is not what patients and their families seek, the tower offers another option—the healing gardens. These four indoor gardens reflect the built-in affinity between man and nature and its impact on our health and well-being. Planned by Barbara Aronson of Shlomo Aronson Landscape Architects, each garden takes as its theme one of the four elements—water, fire, earth and air—and will feature a path with benches surrounded by lush greenery. Both vegetation and flooring will reflect the garden’s theme. For example, the 5th-floor garden’s focus is water: its flooring is green-blue; its plants are water-loving trees, ferns and bamboo; and water trickles through it. It rises three stories—those on the tower’s 2nd, 9th and 12th levels are two-stories high. The garden boasts one entire wall of glass (to be washed by rapelling window cleaners) and is larger than some city pocket parks.

Universally ecofriendly, the building uses solar energy, natural light and ventilation and recycled water. Socket-free radiation-beam heaters warm patient rooms, rooftop centrifugal chillers with magnetic bearings cut power usage, residual heat conserves energy, a computerized lighting system responds to external elements and condensation water from the steam system is recycled.

Described by Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat as “one of the most important buildings in the city,” the Sarah Wetsman Davidson Hospital Tower is the child of many—from donors to designers, dreamers to doers. “It’s a privilege to dream and to realize that dream,” says Dr. Shlomo Mor-Yosef, immediate past director general of the HMO, under whose tenure the tower was conceived and built. “It’s a privilege to say: ‘We did it!’”

The tower’s formal dedication will be at Hadassah’s Centennial Convention in Israel this October.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply