Being Jewish

Hadassah

Feature

Beginnings: A Confluence of Forces

In hindsight, history always looks inevitable. When we look at Hadassah’s 100-year saga, we see the linear version, showing the founding meeting at Temple Emanu-El in New York, the first two nurses dispatched to Palestine and Hadassah’s emergence as the architect of much of Israel’s social welfare foundation.

Written history does not dwell much on the roads not taken. Though Hadassah’s founders had specific goals and boundless energy, they could not predict the obstacles the organization would encounter or the catalytic moments when it would leap forward. And if we can’t be sure of the weather next week, they certainly couldn’t have painted a clear picture of how Hadassah, Israel or the global Jewish family would look in 2012.

Still, history is a more exact discipline than prophecy, and the details behind the timeline reveal not only how Hadassah emerged from the mist of a bygone era but also thrust itself—with help from close friends and distant forces—to the forefront of the Zionist enterprise.

Broadly speaking, Hadassah’s success resulted from three forces: an intellectual climate that promoted the idea of self-determination, the work of individuals and the unpredictable march of events.

Hadassah was part of the larger Zionist revolution, which was an outgrowth not only of the 2,000-year Jewish exile but also a wave of ideas that had begun with the Enlightenment and the American Revolution. The 19th century saw both the emergence of nation states and the abolition of slavery throughout the Western world. By the 1890s, people left behind in the advance of freedom were restless. Jews in particular noticed the difference between free and oppressed nations and began voting with their feet—and, through Zionism, planning their own national destiny.

It was an age of global cognitive dissonance, pitting the promise of liberty against the harsh realities of places like Russia, one of the lands where anti-Semitism increased dramatically in the late 19th century. But the spark that created Zionism came from a place where the ideal and the real were much closer together.

Theodor Herzl, the Viennese journalist who had once advocated conversion to Christianity as the solution to “The Jewish Question,” was working in Paris in 1894 during the opening chapter of the Dreyfus Affair. Herzl viewed French culture as the pinnacle of civilization. What struck him was not so much the condemnation of a Jewish army officer by a military tribunal (many initially thought Dreyfus was guilty). For Herzl, the real shock was the street mob chanting “Death to the Jews.” He came to the conclusion that Jews could only be their own masters in their own land.

One question that came up early in the Zionist story was whether all Jews would be equally free. There is no question that Hadassah was born into a man’s world, and that the founders carved out their own space in a movement that didn’t invite them to the table. But it takes nothing away from Hadassah’s success to recognize that the barriers to women’s participation were not as rigid in the Zionist enterprise as they were elsewhere.

As a revolutionary movement, Zionism was akin to new industries in which rules about who can play are not yet entrenched. The women who attended the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897 did not have voting rights, but by the Second Zionist Congress, in 1898, they did. This is in stark contrast to the United States Congress, which admitted its first woman member in 1917, and the British Parliament, which followed suit in 1918.

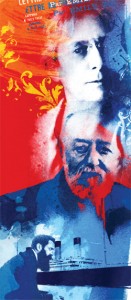

At the helm of Hadassah was an extraordinary woman who all her life performed and behaved as an equal to the men around her. Henrietta Szold was an educator, scholar, writer and editor; she was also the first woman to study at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, taking courses that—70 years later—would have earned her a rabbinical degree. In November 1909, when she was 49, she traveled with her mother to Palestine to see the land of Jewish dreams. She found the public health conditions there closer to a nightmare. Another visitor might have stood in the squalid streets of Jerusalem and given up on the Zionist idea. “Here is work for you,” 77-year-old Sophie Szold told her daughter. “This is what your group ought to be doing.”

The group was the Daughters of Zion, a women’s study circle. A little more than two years later, Szold transformed the circle into Hadassah, and almost immediately the twists of history began to play a role in Hadassah’s development. Six weeks after that foundation meeting in New York, the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic, taking more than 1,500 lives. One of the most poignant and inspiring stories that emerged from the tragedy concerned Isidor Straus, owner of Macy’s, and his wife, Ida. Isidor was offered space in a lifeboat but declined, saying that women and younger men should take precedence. Ida refused to leave the doomed ship without her husband. They died together.

Nathan Straus had accompanied Isidor, his brother and partner, on the trip to Europe. Instead of returning on the Titanic he traveled on to Palestine. When he heard of the selfless way in which his brother and sister-in-law had perished, he resolved to retire from business and devote the rest of his life to philanthropy. His focus would be on public health in Palestine.

Nathan straus knew of Hadassah’s founding and of Henrietta Szold’s philosophy of practical Zionism. In December 1912, preparing to return to Jerusalem, he approached Hadassah with a plan. If the organization could find a nurse and pay her salary for two years, Straus would fund a clinic in Jerusalem. He estimated the cost to Hadassah at $2,500. At the time, Hadassah, less than a year old, had $283 in its treasury.

With less than three weeks before Straus’s departure—he said the nurse would have to sail with him and his wife, Lina—Hadassah began its first fundraising campaign. On January 18, the Strauses set sail with not one but two Hadassah nurses.

Nathan Straus had no hesitation in partnering with a fledgling women’s organization to set up a clinic in Jerusalem. The mission of the first two Hadassah nurses was cut short by World War I, but in 1916, the World Zionist Organization asked the Federation of American Zionists to send a larger medical mission to Palestine. The federation turned to Hadassah because the dispatch of those two nurses gave Hadassah something that no other organization in the movement had—experience in medical mobilization.

The American Zionist Medical Unit was essentially a mobile hospital. It arrived in Palestine in August 1918 with 45 doctors and nurses and 400 tons of supplies. It transformed medical care in Palestine and became the nucleus of the Hadassah Medical Organization.

By the time Israel achieved independence in 1948, Hadassah had opened more than 130 hospitals, clinics, infant welfare stations and dispensaries across the Land of Israel.

Volumes have been written, and more will likely appear, on Hadassah’s remarkable journey. It is a story that could have unfolded in other ways had the world, the Zionist movement or Hadassah’s leaders taken different directions. The important thing to remember is the century of accomplishment that was by no means pre-ordained and by all means real.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply