Books

Personality

Interview: Jonathan Safran Foer

The New American Haggadah is a fresh take of ancient liturgy. It is edited by Jonathan Safran Foer and translated by Nathan Englander—both winners of Hadassah Magazine’s Harold U. Ribalow Prize, Foer for Everything Is Illuminated

(Harper Perennial) and Englander for The Ministry of Special Cases

(Vintage International). Foer has been getting attention recently for the screen version of his book, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) which received an Oscar nomination. And Englander’s latest book of short stories, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank

(Knopf/Vintage), has been getting enthusiastic reviews.

Q. How did you and Nathan Englander come to work on this project, and how long has it been in the works?

A. What inspired me is probably what has inspired so many others to revisit the Haggada. There are supposedly about 7,000 published versions of the Haggada in existence. It is a very rich and beautiful book whether you approach it as a writer or visual artist or a philosopher or a political thinker or as a religious person. And there is something about the book that also inspires and maybe even demands new versions. The central trope of the Seder is this leap of empathy that we are supposed to feel as if we ourselves were liberated from Egypt. Not that we should be recipient or students of a story. In order to bring that about we need a Haggada that engages us powerfully, that makes us complicit in the telling of the Exodus. So it’s no great surprise given the sort of magnetic appeal the book has but also this imperative to engage the audience…it’s no great surprise that a lot of people have wanted to work on it.

I have known Nathan for years and I first got the idea for the Haggada about six or seven years ago. I contacted Nathan probably four or five years ago when I first started getting serious about assembling the thing. He was initially somewhat resistant, if I remember correctly, but he decided to give it a try and then he got completely sucked into it.

Q. Would you say that working on this Haggada was also a personal project?

A. I assume maybe naively that all books are personal projects for their authors or editors. But mine are deeply personal, explicitly personal. The audience I had in mind when I began work on the Haggada was my family. I never once thought what would happen to this book in the world, who would read it, how would they use it. I wanted to make a Haggada that would inspire provocative conversations at my family’s Seder table. I wanted a Haggada that would facilitate the kind of Seder that we always wanted to have, one that was vibrant, generous in spirit and captivating for everyone at the table.

Q. Some contemporary versions of the Haggada either cut out the “boring” parts of the text or relegate them to the back of the book. Or they play up the universality of the holiday of freedom. Why were you interested in keeping it so traditional?

A. Because that’s what it is. I fell in love with the book in the process of working on it (I don’t mean my version, I mean the liturgy). And I became convinced at a certain point that the best way to make this new version would be to go to whatever lengths are necessary simply to get out of the way of the Haggada. The task sounds easier than it is. To get out of the way of the book you might need an entirely new translation, as I was convinced we did. We might need to reconsider the configuration of words on the page, as I was convinced we did. We might need to contextualize the book…and we did it with the timeline that runs graphically across the top. But it’s not a bells-and-whistles book. And it’s not radical and it does not overlay any particular agenda or aspire to satisfy some niche audience. Rather, I tried to make the most powerful and affecting version of this ancient text that I could without sacrificing any of its sanctity.

Q. What do you think is the greatest contribution that Nathan Englander’s translation makes?

A. What I would say…is his translation is lyrical, it’s beautiful, it’s original, it’s extremely readable and accessible. Most importantly, it says what the Hebrew text says. His guiding principal was always very, very simply, to try to convey what the Hebrew conveys. It’s not always possible. In fact, it’s never quite possible but that was always his ambition. So if the Hebrew is ambiguous, then the English should be ambiguous. If the Hebrew is clear, the English should be clear. If the Hebrew makes a certain decision, which seems odd to us now and could easily be brushed aside or smudged in the act of translating, Nathan always chose not to do that.

Q. Why four commentaries—are they representative of the traditional Four Sons?

A. Originally there were 20 or 25 commentators working throughout the book but it felt like an anthology and the commentaries felt sort of like text boxes, so I realized I had to find a way to compress the structure, to limit the number of voices at play, to make them necessary, and have them be in communication with one another…. I certainly was thinking about the four sons with the four voices, although these four voices do not correspond with those four sons.

Mostly, I was thinking, ‘How can I make a book that can be used differently by different people at the table, and can also be used differently over time, again all in the interest of engaging Seder-goers with the hope of bringing about that leap of empathy.’ I chose these four writers because I thought they would be the best for these perspectives, and I was extremely happy with what they came up with.

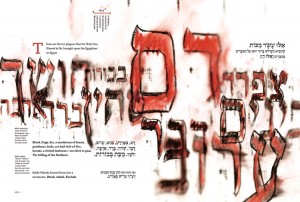

Q. Design-wise, the Haggada has a lot of white space and is pleasing to read. Yet Hebrew fonts become art as words on the pages reflect not only the text but also incorporate styles used in the years noted in the timeline. How did you come to work with designer Oded Ezer?

A. Oded is actually extremely well known in design communities. I think I came across his work in a Museum of Modern Art publication. I had entertained a lot of ideas including figurative artwork. In the end, I really wanted to have as little of the artist’s sensibility as possible and to leave the experience as open as possible for the Seder-goer. And it would have felt inappropriate to have a heavy-handed sensibility because, at the end of the day, it is a religious text. Oded had a number of ideas for what the pages in the Haggada would look like and it was in conversation that we came up with this idea of graphically following the timeline, that the book could be a record, a kind of timeline itself of Jewish lettering, of Jewish text, of Jewish printed matter. I thought that was a brilliant and very, very subtle way to contextualize the book, and it has the added bonus of each page being different, or every other page being different. Which creates a kind of drama as one moves through the book—you want to see what is going to come next. He succeeded by making something visually appealing, which also tells a story.

Q. Was having a timeline a pedagogic decision? How does it add to the Passover reading?

A. It just contributes by contextualizing the story and reminding readers—or telling them for the first time—just how important the story has been. It is not a timeline of Jews; it is a sort of history of the story, the various ways that the story of the Exodus has appeared in Jewish history and in world history and how it has been borrowed by various social justice movements, by various cultures. And it’s thrilling because it makes visible the chain [of which] we are the contemporary link. It reminds us that these words that we are reading to one another have been read for more than a hundred generations for several thousand years. Also, incidentally, I think the timeline is enormously fun to read.

Q. Have you thought of doing a Haggada for kids?

A. I think that there is quite a bit of material in this Haggada for kids and I hope that it would appeal to them. But you know, I’ll see, it’s a great idea, especially because I have kids. There is not a more personal process than being a father, so it is certainly nice to imagine making something that engages my kids and makes that empathic leap for them.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply